A Oneworld Paperback Original

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications 2015

First published by Oneworld Publications, 2015

Copyright Joe Flatman 2015

The right of Joe Flatman to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-503-9

eBook ISBN 978-1-78074-504-6

Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

To Zoe from Daddy, autumn 2014

Contents

Figure 1 | Harris matrix stratigraphic sequence diagram from the medieval Wilds Rents tannery |

Figure 2 | C14 probability distributions of dates from Brisley Farm, Ashford, Kent |

Figure 3 | Excavations under way in advance of a city-centre redevelopment at Eastgate Square, Chichester |

Figure 4 | Archaeologists at work in the historic Rocks district of Sydney |

Figure 5 | Fountains Abbey, North Yorkshire, founded in 1132 CE ; Britains largest monastic ruin and most complete Cistercian abbey |

Figure 6 | Prehistoric footprint impression surviving in the intertidal mud of the Severn Estuary in south-west Britain |

Figure 7 | The Iron Bridge and village of Ironbridge in Shropshire, the birthplace of the global Industrial Revolution |

Figure 8 | Mile castle 39 (also known as Castle Nick), a Roman fortification along Hadrians Wall, occupied until the late fourth century CE |

Figure 9 | Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire |

Figure 10 | The ship is the most common figurative motif in Scandinavian rock art |

Figure 11 | Replica of a thirteenth-century CE model boat found in the Viking city of Dublin |

Figure 12 | Reconstruction of the use of the thirteenth-century CE model boat found in Dublin |

Figure 13 | Archaeologists at work on the wreck of the steamboat Montana , near Bridgeton, Missouri |

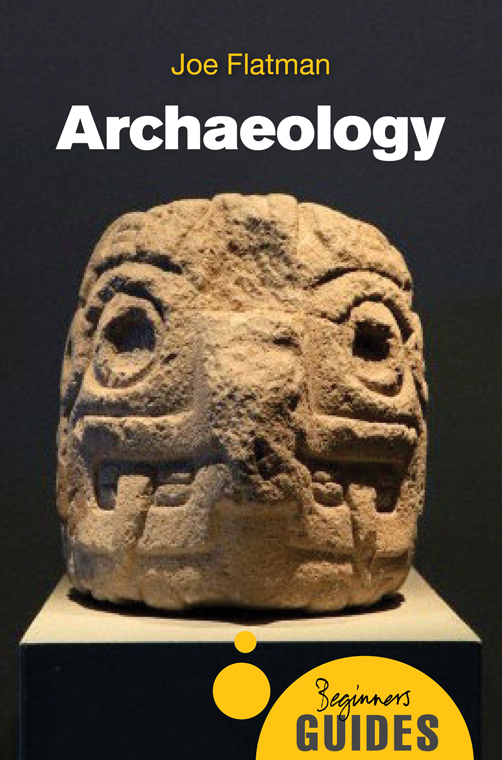

What is (and isnt) archaeology?

In the popular imagination, archaeology is either about travel, adventure and intrigue or about people with marginal dress sense droning on about dusty old bits of pot. The reality lies somewhere in between: most archaeologists can tell you real stories of adventure in a foreign land; all can equally tell of days, weeks or months of painstaking work in a dusty archive or library. Most archaeologists dont stand out in a crowd and live a life much like any other person, driving to the office and spending too long on a computer dealing with emails before calling at the supermarket to pick up some food on the way home. They have families and pets and personal lives; in the evening they watch box sets of DVDs on their television, eat pizza and worry about cleaning the kitchen.

What makes archaeologists different is not normally the nature of their daily lives but rather how they view the world, in particular how they approach and interpret physical remains, both of the present and the past. Having an archaeological training is like having a special pair of glasses that transforms your view of the world: once worn, nothing ever quite looks the same again. From the smallest piece of pottery to a giant building, ship or landscape, approaching the world with an archaeological mindset means having a fundamentally different view of everything, because it involves seeing the present through the lens of all the activities and processes that have gone before. When an archaeologist walks down the street they visualise the layers of previous occupation underlying the modern asphalt and concrete; layers going back perhaps hundreds or thousands of years. When they walk into a building they visualise the buildings that came before that lie buried beneath the modern bricks and mortar; when they sit on the seashore they wonder about the people who hunted and fished along that same shore perhaps tens of thousands of years ago, and when they light a match, cook some food or hold a pen, they think about the countless industrial and intellectual processes that led up to them being able to perform those simple actions. They think about how people a hundred, a thousand or ten thousand years ago would have created fire, found and cooked food or made their mark on the world. Moreover, these archaeologists know how to uncover the physical remains of these past streets, buildings, beaches and objects and how to securely identify, date and protect them for future generations.

This book is more about how to think like an archaeologist than it is about how to be an archaeologist. It uses examples of places, landscapes, objects and peoples from the past and the present to demonstrate how archaeologists approach the world. It explains how archaeologists weigh up the pros and cons of different types of evidence, how they formulate and test hypotheses and how they come to new conclusions about life in the past. And, although focused on archaeological sites, it also uses documentary evidence such as historical texts and photographs, together with artistic evidence such as ancient drawings and carvings, and ethnographic and anthropological evidence such as oral history, photography and interview records, because a good archaeologist is open to all available sources of evidence.

As the doyen of British archaeology Mortimer Wheeler (18901976) wrote in his 1954 book Archaeology from the Earth : the archaeologist is digging up not things but people. As true now as it was then, being an archaeologist means many things but it is certainly never boring, because humans are complex and fascinating creatures, as were the worlds that they built in the past.

Practising archaeology

Put simply, archaeology is the study of past human societies through the analysis of surviving physical remains. It is both a practical and theoretical pursuit. Archaeologys practical focus lies in the development and application of tools and techniques for maximising the search for, and analysis and conservation of, physical remains. But this practical focus does not alone make archaeology. Anyone can search for and recover ancient objects but that is treasure-hunting, not archaeology. What makes it archaeology is the combination of practical endeavour and a theoretical focus. Archaeology means attempting to understand the past, to interpret what the physical remains discovered tell us about how our common ancestors lived, what motivations underlay the making of these objects and how they influenced their landscapes. Archaeologists take pains to communicate this past to non-archaeologists and to involve them in the exploration, discovery, interpretation and protection of historic sites. Any projects that do not involve all of these different processes are not archaeology.

Next page