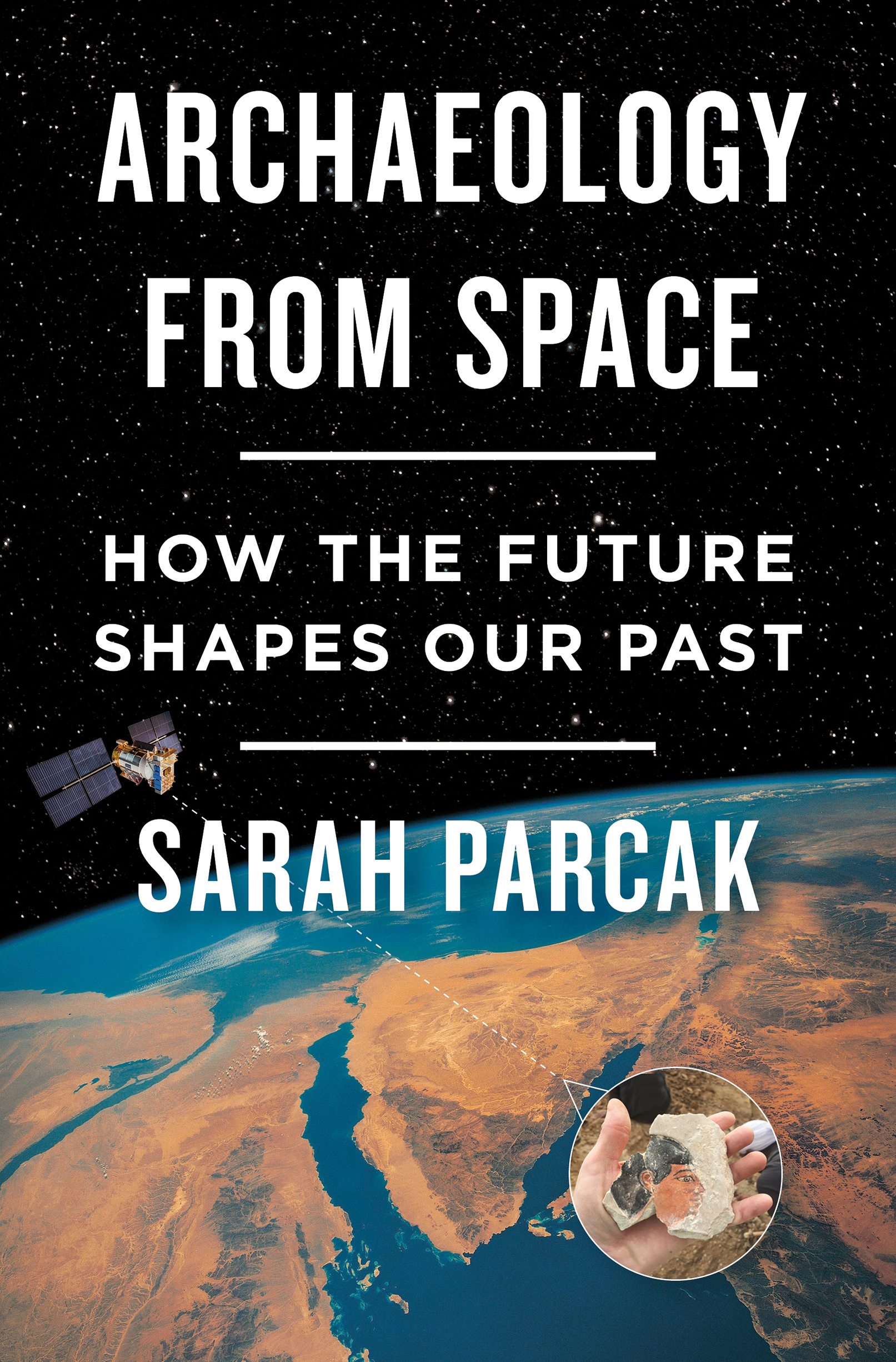

The author will donate a portion of the author advance from this book to support the mission of GlobalXplorer, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization registered in Alabama. This includes fieldwork and field schools in Egypt, training foreign archaeological and cultural heritage specialists in innovative technologies, and empowering a global citizen archaeology movement. If the ideas shared in this book have moved you, I encourage you to visit www.globalxplorer.org to become a space archaeologist in training.

My entire life is in ruins. Quite literally. No, this is not a cry-for-help book, nor a journey of self-discovery. I am an archaeologist. Ive spent much of the last 20 years working on excavations in Egypt and the Middle East, exploring ruins in Central and South America, mapping sites across Europe, and even digging for the occasional Viking. You might say I am obsessed with the dirt beneath my feet and all the wonders that might be there; it doesnt necessarily glitter, but it is priceless. That dirt contains nothing less than the clues to who we are, how we got here, and how we might thrive in the future.

Most of us can look back at our lives and identify pivotal moments that influenced our journey to where we are in our career: an unexpected event, maybe, meeting a key individual, an epiphany of some kind. Something. In my case I can identify one influence rooted in fiction and another solidly founded in facts.

Pizza, Videos, and My Path to Becoming an Archaeologist

If you are a child of the 1980s like me, your Friday night routine might have included getting pizza and picking up a VHS cassette from your local movie rental place. Wow, even writing that makes me feel old. After school, my mom would take my brother, Aaron, and me up the street to a creaky old house that had been repurposed to hold thousands of tapes, categorized by theme and age appropriateness.

Much to the chagrin of my mom, we invariably chose one of three movies: The Princess Bride, The NeverEnding Story, or Raiders of the Lost Ark. (Now that I have a child of my own, who wants nothing more than to watch Minions on repeat, I appreciate my moms purgatory. She laughs at me.)

If we chose Raiders, I would sit, rapt, memorizing every scene, every bit of dialogue, every gesture. I cant tell you if it was Egypt, the sheer adventure, or just Harrison Ford, but that movie called out to me.

At that age, I didnt know that no one-size-fits-all fedora exists for archaeologists. We specialize in diverse subfields: aside from a particular time period or regional focus, an archaeologist might study pottery, art, bones, ancient architecture, dating techniques, or even recording and illustration.

Im part of a relatively new specialism called space archaeology. I am not making that term up. It means I analyze different satellite data setsGoogle Earth is one youre probably familiar withto find and map otherwise hidden archaeological sites and features. Its a pretty cool job, but wasnt an obvious career option when I started taking undergraduate archaeology classes.

Why I do what I do all goes back to my grandfather, Harold Young, who was a professor of forestry at the University of Maine. Every weekend when I was young, while my parents worked late nights at the family restaurant, Aaron and I went to my grandparents house on a hilly tree-lined street in Orono, Maine. Gram and Grampy had retired, my grandfather from the university and my grandmother from her post there as secretary of the faculty Senate.

Gram ruled the Young household, and the Senate, with an iron fist, so much so that Grampy always gave the same response when we asked if we could go outside to play.

Im only a captain, hed say, smiling. Youll need to ask the general! and hed turn to Gram and give a sharp salute. It ticked her off something awful and sent us into fits of giggles.

Grampy and My Journey into Space

Grampy was in fact a captain, having served as a paratrooper during World War II. Part of the US Armys 101st Airborne Division, known as the Screaming Eagles, he had led a platoon and jumped the day before D-Day. He also led one of only six bayonet charges in the war, receiving a Bronze Star with an oak leaf cluster and a Purple Heart. To plot his landing positions and map where to coordinate his troops, he analyzed aerial photographs, cutting-edge technology at the time.

He took that technology with him when he completed his PhD in forestry at Duke University, developing new techniques to map tree heights using aerial photos. For nearly 30 years, Grampy taught generations of foresters how to use such photographs in their research and became a world-renowned forester.

I was only told about Grampys careers in snippets over time. He sometimes disappeared, traveling to far-flung places for international conferences, bringing us back carved wooden elephants from Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). I later learned he donated his entire forestry library to institutions there. When I was little, I didnt understand what it meant to be a decorated war hero or a brilliant scientist. I just knew him as the kind and gentle grandfather who drove Aaron and me up to the campus to visit the cows in the research barn, where we would get freshly made chocolate milk if we were well behaved, which was rare. To this day I still think chocolate milk comes from chocolate cows.

Most of all, I remember how hed let us look through his stereoscope, like a set of desk-top binoculars, under which you put two slightly overlapping aerial photographs. The effect is wonderfulthe photos jump out in 3-D. Its not something you forget, if youre young and impressionable, and it mapped out the first steps on my path.

Like so many in the Greatest Generation, Grampy never spoke about his war service. I did try to interview him for a high school project, but those days, thank God, were behind him. The forest was safe, and full of trees to map and identify, and thats where he took us, without fail. Grampy ran three miles every day, and still had the strength to walk around the neighborhood the day before he died from cancer.

Three years after we lost him, as I gradually learned more about his research, I increasingly regretted never discussing it with him. By then, his research papers were available online, and my curiosity about his work had deepened to the extent that I took an introductory class on remote sensing in my senior year in college. Grampy had never gotten into satellite imageryit came into use in forestry about 15 years after he retiredbut I wondered just how different it could be from his aerial photography. Besides, most archaeologists had probably already included the technology in their research, especially in Egypt. Right? Everything had likely been mapped. Oh, naivety!

I started to get a clue when I tried to find papers for my final project, using satellites to detect water sources near archaeological sites in Sinai, Egypt. You know youve hit a dead end when the handful of sources cite each other. That one class led to a master of philosophy thesis, which led to a PhD, and now nearly two decades of research. I have my grandfather to thank for my career.