Contents

Guide

Published by National Geographic Partners, LLC

1145 17th Street NW, Washington, DC 20036

Copyright 2021 National Geographic Partners, LLC. Introduction copyright 2021 Douglas Preston. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williams, A. R. (Ann R.), editor. | Preston, Douglas J., writer of introduction.

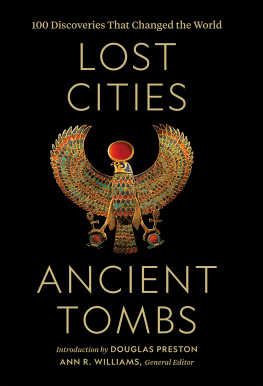

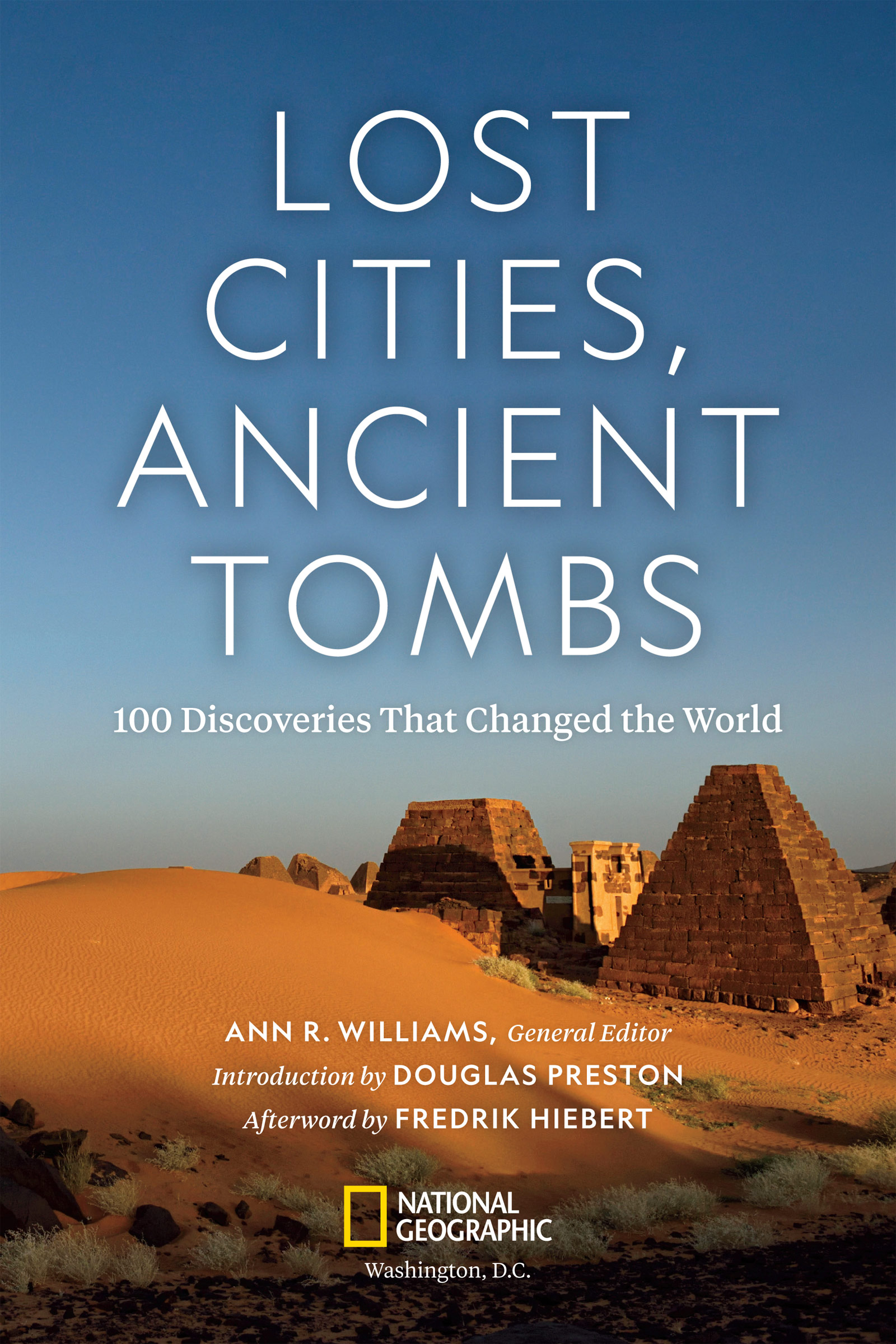

Title: Lost cities, ancient tombs : 100 discoveries that changed the world / general editor, Ann R. Williams ; introduction by Douglas Preston.

Other titles: One hundred discoveries that changed the world

Description: Washington, D.C. : National Geographic, [2021] | Includes index. | Summary: The story of human civilization, as told through 100 key discoveries spanning six continents, including firsthand reports from explorers, scientists, and antiquarians-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021014585 (print) | LCCN 2021014586 (ebook) | ISBN 9781426221989 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781426221996 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology. | Civilization, Ancient. | Extinct cities. | Tombs.

Classification: LCC CC165 .L628 2021 (print) | LCC CC165 (ebook) | DDC 930.1--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021014585

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021014586

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 14,000 research, conservation, education, and storytelling projects around the world. National Geographic Partners distributes a portion of the funds it receives from your purchase to National Geographic Society to support programs including the conservation of animals and their habitats.

Get closer to National Geographic Explorers and photographers, and connect with our global community. Join us today at national geographic.com/join

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights: bookrights@natgeo.com

Interior design: Nicole Miller

21/EV/1

M ost great archaeological discoveries involve a transcendent moment of revelation. That moment came for Howard Carter when he first peered into the dimness of King Tuts tomb and exclaimed, Everywhere the glint of gold. It arrived when Donald Johanson and Tom Gray spied a small fragment of arm bone sticking out of a slope, revealing the remains of the celebrated Lucy. And for Robert Ballard, it came on September 1, 1985, at 1:05 in the morning, when video cameras on a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) illuminated the gigantic boilers of a large wreck on the seafloor, and he knew he had found the Titanic.

But these thrilling moments give a misleading impression of how key discoveries are made. The vast majority take years to develop and are often the culmination of tedious research, false starts, failures, political opposition, professional doubt and even disparagement, permitting vexations, bureaucratic nightmares, and dreary fundraising. The discovery of a pre-Columbian city in Honduras, which I participated in (see page 392), followed that pattern, taking 20 long and frustrating years. In 1996, I happened to be visiting NASAs Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, researching a story for National Geographic magazine on the mapping of Angkor temples from space. One of the scientists, Ron Blom, mentioned in passing a confidential project he was working on for an amateur archaeologist and filmmaker named Steve Elkins. Blom was searching satellite imagery for a legendary lost city in Honduras called Ciudad Blanca, the White City, or the Lost City of the Monkey God, and his analysis had identified possible unnatural rectilinear and curvilinear features in an unnamed valley surrounded by steep, densely forested mountains, with only one point of access. It was one of the last scientifically unexplored places in Central America, truly a lost world.

I began following Elkinss struggles to investigate the mysterious valley. His efforts were stymied again and again by various fiascoes, including lack of money, unreliable partners, failed attempts, Honduran military coups, political turmoil, and a deadly hurricane. Fifteen years went by, and it seemed the project was about as dead as it could get. And then, quite suddenly, it came together. By adopting a technology called lidarlight detection and rangingElkins realized he could map the 20 square miles of the valley from the air in less than a week. There was no need to go in on the ground, a daunting and dangerous prospect. Elkins and his team raised close to a million dollars and engaged the expertise of the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) at the University of Houston. In 2012, I accompanied the team and a plane carrying a lidar machine to Honduras. To be frank, I was deeply skeptical. It seemed crazy that a lost city could still be found somewhere on the surface of the earth in the 21st century.

For three days in May, the lidar plane flew in a lawn-mower pattern over the target area, firing billions of harmless laser pulses into the canopy, a tiny fraction of which reached the ground and bounced back, thus allowing the terrain underneath to be scanned. The data was collected and uploaded to Houston, processed, and downloaded back to our base of operations. We saw the first scans on Sunday, May 5.

That was, to be sure, an astonishing moment of discovery. When the images popped up on the lidar engineers laptop, you didnt have to be an archaeologist to see the plazas, terracing, and the monumental structures of a major, prehistoric site. Along with everyone else, I was stunned.

And yet, curiously enough, that wasnt for me, personally, the moment of discovery. There was a city there, to be sure, but it was still abstract, a collection of geometric patterns on a black-and-white lidar plot. The real moment didnt come until 2015, when, in a joint Honduran-American expedition, we were able to explore the ruins on the ground. After three years of anticipation, the actual experience of entering the lost city was a disappointment. The jungle was so thick that, even standing in the central plaza facing the main earthen pyramid, we could see nothing but tree trunks, leaves, and vines. The second day exploring the city was particularly miserable. Incessant rain sounded a dull roar in the treetops and streamed down everywhere. Thoroughly drenched, I had shed my useless raincoat, and we were filthy from wallowing through waist-deep muck holes and scrambling up muddy slopes. I could feel countless tiny chiggers burrowing into my flesh around my waist and ankles.

After many hours macheting our way through several plazas and earthworks of the ancient city, still unable to see much, we decided to call it a day and return to camp. As we were walking back along the base of the pyramid, a team member shouted, Hey, there are some weird stones over here. We all converged to where he was pointing, an area we had walked past many times.