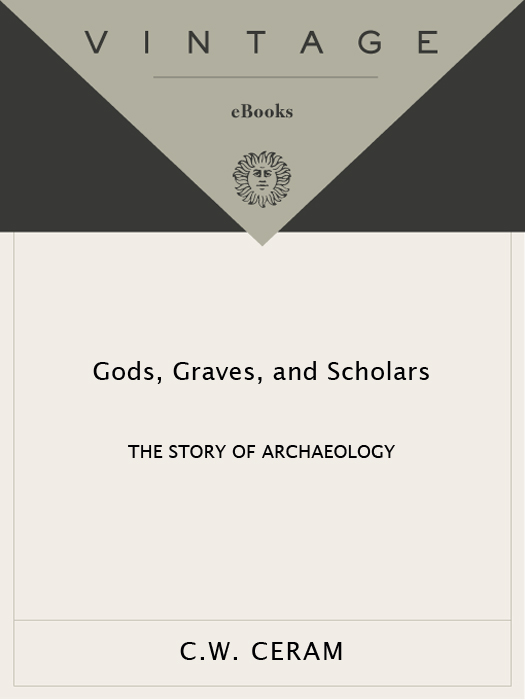

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, August 1986

Copyright 1951, 1967 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Copyright renewed 1979 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in German as Gtter, Grber und Gelehrte, copyright 1949, 1967 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH., Hamburg-Stuttgart. This translation originally published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in 1951 and in a revised edition in 1967.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ceram, C. W., 19151972.

Gods, graves, and scholars.

Translation of: Gtter, Grber und Gelehrte.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Knopf, 1967.

Bibliography: p.

1. ArchaeologyHistory. I. Title.

CC100.C4213 1986 930.1 86-11131

eISBN: 978-0-307-81427-2

v3.1

There is no such thing as a patriotic art or a patriotic science. Both art and science belong, like every higher good, to all the world and can be fostered only by the free flow of mutual influence among all contemporaries, with constant regard for all we have and know of the past

Goethe

He who wants to see his time rightly, must look upon it from a distance. How great a distance? Quite simply, just far enough away so that he cannot discern Cleopatras nose

Ortega y Gasset

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND,

REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION

Since the original German edition of this book was published in 1949, it has been translated into twenty-six languages and read by millions of people, even though I have never permitted a reprint edition to be issued. While Gods, Graves, and Scholars was originally written for the widest general reading public, its strict adherence to scientific standards has led long since to its being made required reading for some college courses. University and college libraries often stock as many as ten copies or more in order to be able to satisfy the demand for the book, which my publisher and a number of critics have called a classic.

In the meantime, archology has marched on. New discoveries have been made, new interpretations advanced, and above all, remarkable new techniques for archological researches developed. To cover these new developments, I have revised the original edition and concluded the book with a summary of the important new findings and methods. The extensive additions to the original American text have been translated from the German by Sophie Wilkins, to whom I particularly wish to express my appreciation also for her painstaking work in comparing texts and making necessary rearrangements in the revised edition.

Gods, Graves and Scholars was followed by The Secret of the Hittites: The Discovery of an Ancient Empire (1956), The March of Archology (1958), a pictorial history of archology, and Hands on the Past (1966), a documentation. Together these four volumes, with their combined total of nearly a thousand bibliographical items and picture sources, constitute the most comprehensive history of archology ever published for the general reader, containing numerous facts and stories long forgotten even by the specialists, as well as the latest developments and scientific thought in the field.

C.W.C.

July 1967

FOREWORD TO

THE FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

My book was written without scholarly pretensions. My aim was to portray the dramatic qualities of archology, its human side. I was not afraid to digress now and then and to intrude my own personal reflections on the course of events. Nor have I shied away from prying into purely personal relationships. All this has produced a book that the expert may condemn as unscientific.

But I wanted the book to be that way. Archology, I found, comprehended all manner of excitement and achievement. Adventure is coupled with bookish toil. Romantic excursions go hand in hand with scholarly self-discipline and moderation. Explorations among the ruins of the remote past have carried curious men all over the face of the earth. Yet this whole stirring history, I discovered, was hopelessly buried in technical publications that, however great their informative value, were never written to be read. I also learned that not more than three or four attempts had ever been made to bring this dramatic story to light. Yet in truth no science is more adventurous than archology, if adventure is thought of as a mixture of spirit and deed.

Though my method allows little scope for pure description, I am still deeply obligated to learned writings on antiquity. It could not be otherwise. Inded, my book is a hymn of praise to the archologists brilliant accomplishments, his penetration and indefatigability. Above all, it is a memorial to those investigators who, out of genuine modesty, have hidden their light under a bushel. With a sense of responsibility toward these little-known people who make up the backbone of the archological profession, I have tried hard to avoid false groupings and false emphases.

I realize that the specialist who reads my book will probably discover certain defects. To some extent this is inevitable. When I began writing, for example, the mere spelling of proper names loomed as an almost insurmountable obstacle. More than once I had a choice among a dozen different spellings of the same name. I finally decided to follow the commonest usage and eschew any scientific principle that, in places, might have led to complete unintelligibility: If the great German historian Eduard Meyer, faced with a similar problem in his History of Antiquity, could say, speaking to the scholars themselves, here I saw no other way than to proceed without any principle whatever, the author of a mere report may surely do likewise.

Beyond this, of course, simple factual mistakes have undoubtedly crept into the text. Some delinquency, I believe, is quite unavoidable, considering the tremendous amount of material drawn from four specialized fields that I have tried to compress.

I am indebted, moreover, not only to archology, but to the writers of sound scientific popularizations, who have showed me what can be done in this form and whom I have earnestly attempted to emulate. To the best of my knowledge it was Paul de Kruif who first undertook to trace the development of a highly specialized science so that one could read about it with genuine excitement, with the sort of response too often produced, in our times, only by detective thrillers. De Kruif found that even the most highly involved scientific problems can be quite simply and understandably presented if their working out is described as a dramatic process. That means, in effect, leading the reader by the hand along the same road that the scientists themselves have traversed from the moment truth was first glimpsed until the goal was gained. De Kruif found that an account of the detours, crossways, and blind alleys that had confused the scientistsbecause of their mortal fallibility, because human intelligence failed at times to measure up to the task, because they were victimized by disturbing accidents and obstructive outside influencescould achieve a dynamic and dramatic quality capable of evoking an uncanny tension in the reader. The title of his book, The Microbe Hunters, transforming as it did the dryly scientific term