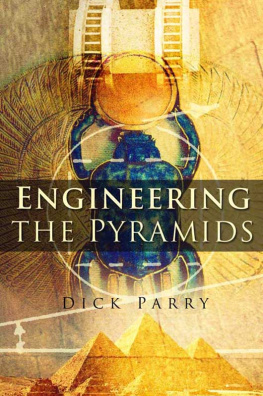

ENGINEERING

THE

ANCIENT

WORLD

ENGINEERING

THE

ANCIENT

WORLD

DICK PARRY

First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Sutton Publishing

Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Dick Parry, 2005, 2013

The right of Dick Parry to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9550 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The full-scale rolling tests to explore this possible method for transporting and raising Pyramid stones were financed and carried out in Japan by the Obayashi Corporation in 1996, while those relating to the Stonehenge bluestones were carried out in 1998 on the mountainside of Carne Meini, immediately below the bluestone outcrop, as part of the TV programme Stonehenge: Secrets of the Stones produced by Yorkshire Television. The many extracts from Herodotus, The Histories , are reproduced with the kind permission of Penguin Books Limited, and I am grateful, too, to Cambridge University Press for permission to include extracts from Science and Civilisation in China by Joseph Needham, Lu Gwei-Djen and Ling Wang. I am much indebted to my good friend Demetrios Coumoulos for assisting me in obtaining information on the Eupalinos tunnel. My thanks also to Christopher Feeney, Hilary Walford, Jane Entrican, Victoria Carvey and other staff members at Sutton Publishing who have contributed to making the book a reality.

PREFACE

This book owes its existence largely to a man who lived nearly 2,500 years ago. When gathering material for my book Engineering the Pyramids I found that the best description of the construction of the Great Pyramid, or anyway the one that convinced me the most, was that by the Greek historian Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC. But, perhaps more importantly, I came to realise that our understanding of a number of the engineering achievements of our ancient forebears owes much to the writings of Herodotus. Most of those writing about Herodotus, whether laudatory in their comments or otherwise, have been classicists, and, not surprisingly, the engineering achievements of the time have not been their primary consideration. We are fortunate that Herodotus was a keen observer, had a curious mind, and had the ability to glean information from the priests and other informed people he met or sought out during his extensive travels. Cicero saw him as the Father of History and, as he might well be the most quoted (and misquoted) author in any field, this seems to be a reasonable claim; but there have been, and still are, those who view him in a different light. He was certainly a teller of tall tales, but he invariably makes it clear that he is simply repeating something told to him: a modern historian would be expected to judge such bits of information critically and weed them out, or suffer the opprobrium of his peers; but Herodotus, free of precedent and peers, leaves the reader to make what he or she will of them.

The world Herodotus knew, or knew about, comprised the countries fringing the Mediterranean, and extending eastward at least as far as the Persian Gulf. He also had some acquaintance with areas fringing the Black Sea. His knowledge of the geography and history of these areas came from his own observations and discussions with local people, other travellers and learned persons, such as priests, during his travels and to a limited extent from existing texts, such as the writings of Hecateus. It is clear from his many references to ancient works that he recognised that the world he knew owed much to the engineers who had devised the means to cross rivers, traverse the land, irrigate the crops, supply water for human construction, and build the great temples and tombs. It was these engineers, and not the great kings or their armies, who established the very foundations of civilisation. An appreciation of the work of these ancient engineers must not be limited to the works described or mentioned by Herodotus; but it is he who provides us with an excellent starting point from which we can look back to the great accomplishments preceding his time (many of which still existed in, or influenced, the world he knew), and forward to the great accomplishments that came after his time, which, in some instances, owed much to the knowledge accumulated before and during his time.

During his lifetime much of the world known to Herodotus, outside Greece itself, was under Persian control. But it was a world that over the previous three millennia had experienced a kaleidoscope of changing civilisations, each benefiting from the knowledge and technological expertise of its predecessors and sometimes its neighbours; each, in turn, advertently or inadvertently passing knowledge to later successors. Born in Halicarnassus around 480 BC, at a time when it was under Persian control, Herodotus moved to the island of Samos as a young man, perhaps frustrated by the heavy hand of authority in his home town. His interests during his lifetime ranged far and wide, and, in addition to his account of the construction of the Great Pyramid, he has given us descriptions of engineering works as diverse as the ancient Suez Canal, Lake Moeris and its water supply from the Nile, the tunnel of Eupalinos on Samos, the pontoon bridges of Darius and Xerxes constructed to cross the Bosphorus and Hellespont respectively, diversion of the Euphrates at Babylon, the great walls, moat and ziggurat of Babylon, and the great sepulchral mound of Alyattes. One of his descriptions, of a labyrinth close to Lake Moeris, has been the subject of speculation and discussion in modern times. Despite his claim that it surpassed the pyramids themselves, there is no evidence that such a remarkable building existed, although the site can be identified and some sort of structure certainly occupied it. Diodorus also gives a description of the labyrinth, which he believed to be a common tomb for twelve leaders who ruled simultaneously as kings in Egypt.

It was several hundred years after Herodotus that other writers such as Diodorus Siculus ( c. 80 BC20 BC) and Strabo ( c. 64 BCad 25) gave similar prominence to engineering achievements in their writings. It was also in the first century BC that Vitruvius produced his Ten Books of Architecture , essential reading not only for Roman engineers and architects, but also for Renaissance luminaries such as Alberti, Bramante, Michelangelo and Palladio. Vitruvius lists the three essentials of good building as durability, convenience (i.e. function) and beauty, but also stresses the importance of economy, which he denotes as the proper management of materials and of site, as well as a thrifty balancing of cost and common sense in the construction of works. In the first century ad, Frontinus, Roman Consul, onetime Governor of Britain and later to occupy the high office of Manager of Aqueducts at Rome, produced his treatise on the Aqueducts of Rome .

The remarkable civil engineering achievements of the ancient world were not, of course, confined to the world known to Herodotus. The great megalithic structures of Malta and Western Europe pre-dated the Greek historian by 2,000 years and more. Great irrigation schemes and other works were instigated in China and Sri Lanka. Herodotus knew of a country far to the east inhabited by strange animals and humans with strange habits, but certainly did not know of the advanced Harappan civilisation situated along the Indus River, which pre-dated him by 1,500 years.

Next page