Contents

Guide

Page List

A

WORLD

BENEATH

THE SANDS

The Golden Age of Egyptology

Toby Wilkinson

I dedicate this book, with deepest gratitude,

to the memory of Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge,

Egyptologist and author, for his generosity in endowing a

fund for Egyptology at Christs College, Cambridge;

and to successive Masters, Fellows and Scholars of Christs

for maintaining and nurturing the Lady Wallis Budge Fund

over the past eighty-five years. Its beneficiaries (of which

I am proud to be one) have played, and will continue to play,

their part in shaping Egyptology.

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Mono

Colour

On my approaching the temple, the hope I had formed of opening its entrance vanished at once; for the amazing accumulation of sand was such, that it appeared an impossibility ever to reach the door.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA BELZONI, 1821

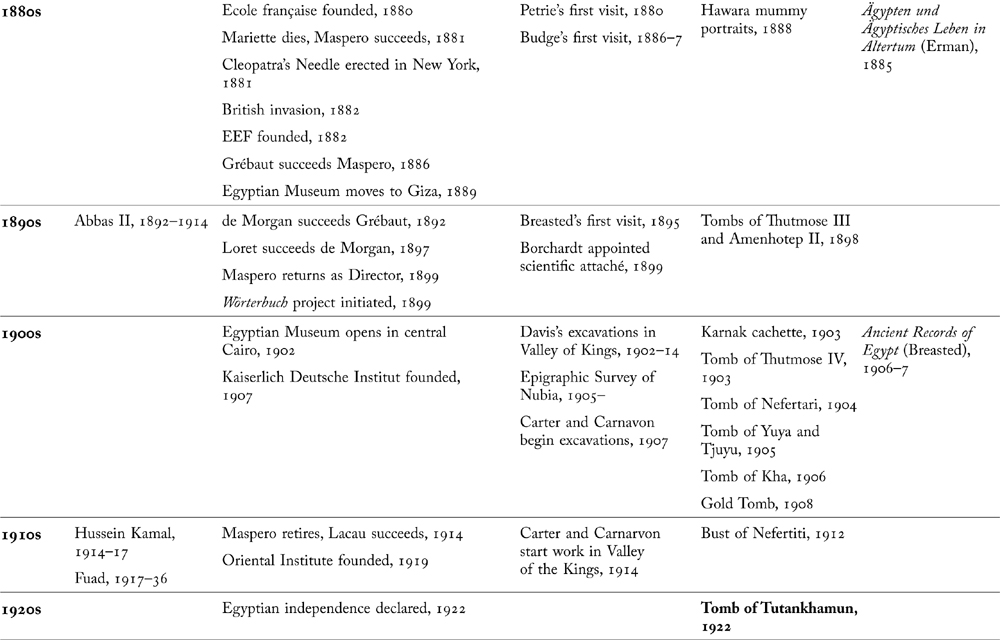

R udyard Kipling wrote of archaeology that it furnishes a scholarly pursuit with all the excitement of a gold prospectors life. If that is true of archaeology, it is all the more true of Egyptology. For what could be more exciting, more exotic or more intrepid than digging in the sands of Egypt in the hope of discovering golden treasures from the age of the pharaohs? The antiquities of the Nile Valley have a special allure, a particular romance, that have spoken to the Western imagination for centuries. Our fascination with ancient Egypt goes back to the ancient Greeks, while the practice of collecting Egyptian antiquities was already well known in ancient Rome. But the heyday of Egyptology the period when it emerged from its antiquarian origins to develop as a proper scientific discipline, and the period that witnessed all the great discoveries, prompting recurrent bouts of Egyptomania in the West was undoubtedly the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This golden age of scholarship and adventure is neatly bookended by two epoch-making events: the decipherment of hieroglyphics in 1822, and the discovery of Tutankhamuns tomb exactly a hundred years later. The first provided the key to unlocking the secrets of pharaonic civilization, and initiated a headlong rush to find out more, sparking intensive Western engagement with Egypt. The second revealed the full glory and sophistication of pharaonic civilization, and gave legitimacy to the Egyptians desire for self-determination, sounding the death knell for Western dominance in the countrys affairs.

As we approach the bicentenary of decipherment and the centenary of Tutankhamuns rediscovery, there has never been a better time to retell and, in retelling, to reassess the story of Egyptology. New discoveries, new research and new insights since 1922 have transformed both our understanding of ancient Egypt and the discipline of Egyptology itself. Recent years have seen an upsurge of interest in the early history of archaeology and travel in the Middle East; many of Egyptologys nineteenth-century protagonists its lesser-known figures, as well as its more famous names have been the focus of detailed biographical study; and the opening up of private and institutional archives has shed new light on the motives and methods of archaeologists and their imperialist colleagues.

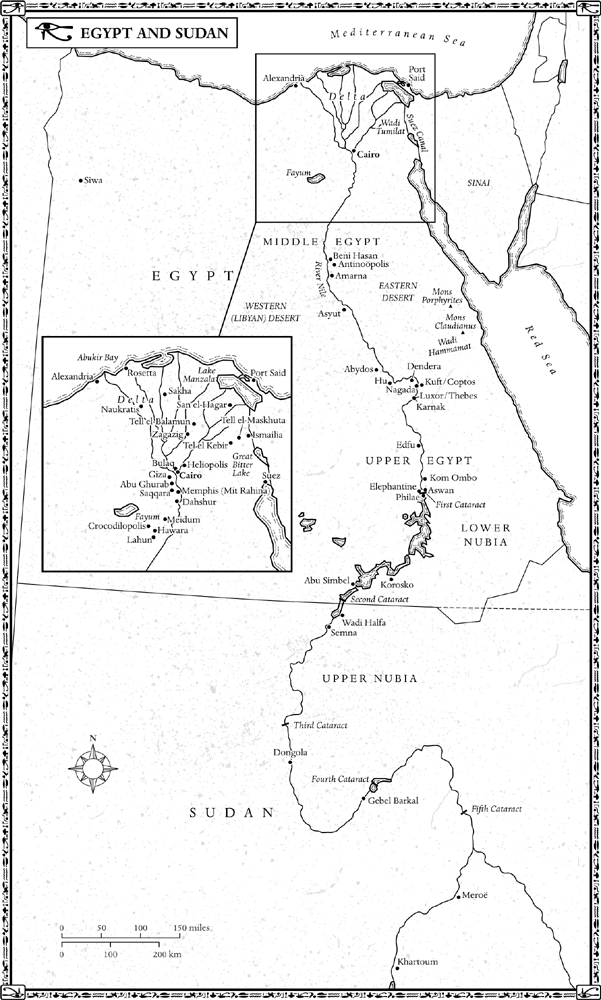

Indeed, the close relationship between scientific excavation and colonial expansion has emerged as a major theme in recent studies of Egyptology. As one scholar has observed: For rising empires, both ancient and modern, Egypt has always been a symbol of ancient sovereignty. This has long been understood and appreciated. When Julius Caesar sailed up the Nile with Cleopatra, the trip was a double celebration: on a personal level, it marked his amorous conquest of the most famous woman in the world; on a political level, it announced Romes vice-like embrace of the fabled land of the pharaohs. Shortly afterwards the Romans began the practice of appropriating archaeological monuments in order to demonstrate their hegemony, and their successors the colonial powers of Western Europe and, latterly, America followed suit. Roman emperors may have been content to ship the odd Egyptian obelisk, sphinx or statue back to the imperial capital, to adorn public spaces and private retreats, and to signal both their sophisticated taste and their all-encompassing authority, all the while squeezing every drop of profit out of their Egyptian possessions. European and American interest in Egypt was more complex, if no less naked. The exploration and description of the Nile Valley and its antiquities carried out, with an accelerating pace, throughout the nineteenth century was motivated by religious, philosophical or antiquarian interests, and helped to create and shape the new disciplines of archaeology and Egyptology; but these ostensibly scholarly activities also served, wittingly or unwittingly, to open up Egypt to Western involvement and interference, economic, social and political. From its very inception, Egyptology was thus the handmaid of imperialism, in a manner that Caesar would have recognized and applauded.

At the same time, Egypts exposure to Western influences some willingly encouraged, many impossible to resist served to change Egyptian society from the inside. During the course of the nineteenth century, notions of modernity, progress, and national identity concepts that had barely stirred in Egypt during the preceding 1,800 years of foreign occupation and control slowly began to take root. By the beginning of the twentieth century, after a hundred years of engagement with foreigners, Egyptians themselves had begun to think about, and plan for, their own independent future. The story of Egyptology is thus also the story of Egyptian self-determination. The detailed understanding and appreciation of the countrys ancient past paved the way for its modern rebirth. As the West rediscovered Egypt, so Egypt discovered itself.

This book seeks to tell both stories, for they are deeply interwoven. It also seeks to take a balanced approach; for Western interest in Egypt, despite the arguments of some commentators, was neither wholly malign nor wholly benign. In the world of antiquarianism and archaeology there were good and bad individuals, scholars and scoundrels, those motivated by a desire for knowledge and those motivated by personal greed. So too, in the world of economics and politics, some (albeit rather few) had genuine aspirations for Egypts development, while others (all too frequently) saw a chance for making a fast buck. Western engagement with Egypt featured more than its fair share of charlatans and condescending imperialists, but also a handful of more enlightened souls who sought to understand the Egyptians on their own terms, sympathized with their predicament, and sought to ameliorate their condition. They, too, are part of the tapestry that is the history of the golden age of Egyptology.