Copyright 1964 by Elizabeth Ann Payne. Copyright renewed 1992 by Elizabeth Ann Payne and Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published by Random House, Inc., in 1964.

www.randomhouse.com/kids

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Payne, Elizabeth Ann. The pharaohs of ancient Egypt. (Landmark books)

SUMMARY : Discusses the life and history of ancient Egypt from the earliest times through the reign of Rameses II, as it has been pieced together from the work of archaeologists. 1. PharaohsJuvenile literature. 2. EgyptCivilizationTo 332 B.C .Juvenile literature. [1. EgyptCivilizationTo 332 B.C . 2. Kings, queens, rulers, etc.] I. Title. [DT83.P3 1981] 932.01 80-21392 eISBN: 978-0-307-81399-2

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon and LANDMARK BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

v3.1

It began to look as though the world would

never know what the ancient Egyptians had to

say about themselves.

Then came a hot summer day in 1822just twelve months after Napoleon had died in lonely exile on the island of St. Helena.

All that morning a young Frenchman named Jean Franois Champollion had been working over a sheaf of hieroglyphs on his desk. As the clock struck noon, he rose unsteadily to his feet. Gathering up his papers, he rushed to a nearby library where his brother was working. Flinging his papers down on his brothers desk, Champollion cried: Je tiens laffaire! Je tiens laffaire! [Ive got it! Ive got it!]

And then he fainted dead away.

Contents

The Rediscovery of Ancient Egypt

A.D . 1798 to A.D . 1822

O n a sweltering August morning in the year 1799, the Egyptian sun beat down on a scene of frenzied activity in the Nile River Delta. There, not far from a little town called Rosetta, a company of French soldiers was digging with a speed born of desperation. They were members of young Napoleon Bonapartes Egyptian Expeditionary Force. And they were under threat of attack from both land and sea.

All morning their commanding officer, Major Pierre Bouchard, had forced himself to move cheerfully among his men. But now, his back to his troops, he was staring bleakly out at the Mediterranean Sea. It was useless to go on acting as if all were well. The French army faced disaster. Napoleons Egyptian campaign, which had begun so brilliantly, was ending in catastrophe.

Just twelve months earlier, Napoleon had conquered Egypt in a lightning campaign of three weeks time. From that moment on, everything had gone wrong. England, fearing that French control of Egypt would threaten her vital land and sea routes to India, had ordered her fleet to the Mediterranean. Shortly after Napoleon had entered Cairo in triumph, the British navy surprised the French fleet at anchor near Alexandria. In a fierce naval battle, the English blew up and sank most of Napoleons ships, leaving Bonaparte and his forces stranded in Egypt.

Hard on the heels of this first calamity came a second. Egypt belonged to the Turks in 1798; it was part of their vast Ottoman Empire. Napoleon had assumed that the aged Turkish Empire was too enfeebled to fight his seizure of the Nile Valley. But Bonaparte was wrong. Not long after the British had destroyed the French fleet, the outraged sultan in Constantinople declared war on the upstart French general. Turkish troops and ships were dispatched southward to throw him out of Egypt.

And this was not all. Blockaded by the British and beset by the Turks, the stranded French faced still another enemy. Egypts military aristocracy, the fierce Mameluke cavalrymen, refused to accept defeat. After their first rout by Napoleon, they had galloped off into the desert to regroup their forces. Now they were reported to be thundering back toward Cairo, bent on revenge. Faced with these three formidable foes, the desperate French were digging in wherever they found themselves.

Major Bouchard!

Behind Bouchards back, a soldier had scrambled up over the top of his trench. There was a puzzled expression on his grimy, sweat-streaked face.

Major Bouchard, sir!

The call brought Bouchard back to the present. He turned, saw the beckoning soldier and made his way through the heat and dust and confusion to the mans side.

Beg pardon, sir, the soldier said uncertainly. It may be nothing, but would you have a look down there?

Bouchard bent forward. In digging a trench, the soldier had uncovered the ruins of an old wall. Embedded among its crumbling yellow bricksand winking up at Bouchard like a huge black diamondwas a chunk of polished stone. It was about two and a half feet across and three and a half feet high.

In spite of his troubles, Bouchard felt a flicker of interest. For the face of the stone seemed to be almost completely covered with a chiseled inscription. The Major jumped down into the trench for a closer look.

Squatting on his heels and narrowing his eyes against the suns glare, Bouchard studied the stone with surprise. Its flat surface was divided into three sections. And each section was engraved with a block of writing in a different language.

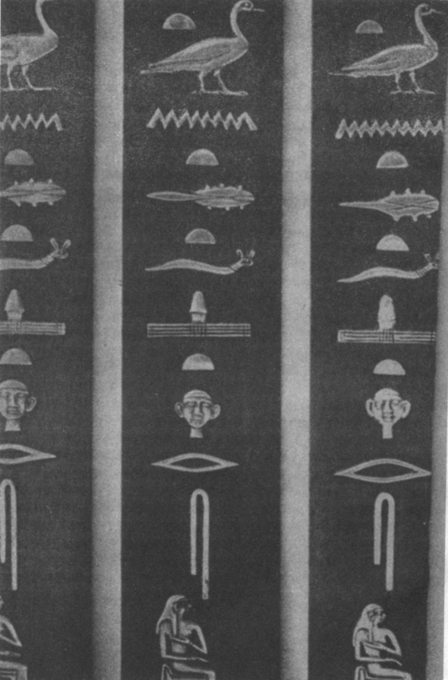

Across the top of the stone were fourteen lines of what Bouchard recognized as hieroglyphs, the mysterious picture-writing used thousands of years ago by the ancient Egyptians. Directly below the hieroglyphs were thirty-two lines of a script Bouchard had never seen before. And crowded across the bottom of the stone were fifty-four lines of Greek.

Bouchard grunted and straightened up. The soldier was watching him anxiously. In view of General Bonapartes order, sir, he said, I thought

Bouchard cut him short with a nod of approval. Everyone in the expeditionary force knew of Napoleons interest in ancient Egyptian history. Bonaparte had ordered his men to report at once any old curios or works of art they might come across in the course of their duties.

Well, Bouchard thought, the engraved chunk of stone was certainly ancient and undoubtedly a curio. But Napoleon was surely too hard-pressed at the moment to interest himself in an old fragment of black basalt. Still, an order was an order. With a shrug, Bouchard arranged to have the stone dug out of the ruined wall, and then reported the find to his superiors.

The black basalt was sent to Alexandriaand Bouchard forgot all about it. He had no idea that he and his soldier had made one of the most exciting archaeological discoveries of all time. For the Rosetta Stone, as the chunk of basalt came to be called, turned out to be the key to the lost history of ancient Egypt.

In Napoleons day historians knew almost nothing about Egyptpast or present. It was a land the world had all but forgotten.

And yet once, long before the birth of Christ, Egypt had been the most famous and powerful country in the world. At a time in history when the ancestors of Western man still lived as semi-savages in the dense forests of England and Europe, a great civilization had existed along the banks of the river Nile. Ruled over by awesome god-kings called Pharaohs, Egypt had been a land of bustling cities, golden palaces, huge stone temples, busy dock sides and luxurious country estates. Her people had been fun-loving and light-hearted, her nobles elegant and worldly and her gods the most powerful in all the world.