A t one time scholars believed that the civilization of ancient Egypt was the first in the history of the world and the progenitor of all others. We now know this to be untrue, but the ancient Egyptians retain one unique distinction: they were the first people on earth to create a nation-state. This state, embodying the spiritual beliefs and aspirations of the Egyptian race, was in all its major manifestations a theocracy. It served as the framework of a culture of extraordinary strength, assurance and durability which lasted for 3,000 years and which retained almost to the end its own unmistakable purity of style. In the Egypt of antiquity, State, religion and culture formed an indisputable unity. They rose together; they fell together, and they must be studied together.

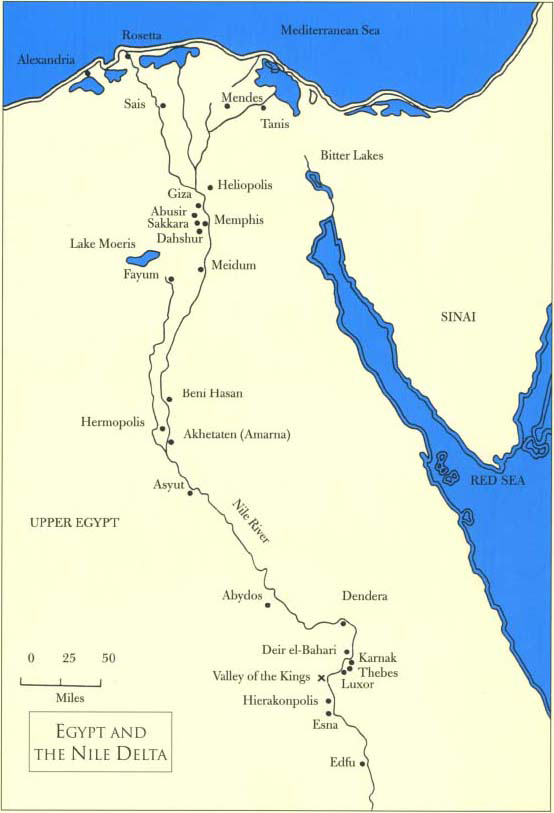

Moreover, there was a fourth essential element in this creative unity: the land. It is impossible to conceive of the civilization of ancient Egypt except in its peculiar geographical setting. It was nurtured and continued to be dominated right to the end by the physical facts of its setting: the rhythm of the Nile and its productive valley, and the circumscription of the desert. They gave the Egyptian people and their culture certain fundamental characteristics: stability, permanence and isolation. The Egyptians, indeed, were self-consciously aware of their national immobility and separateness. They assumed they had always inhabited the Nile valley as a distinctive race; and that the valley, with its enclosing deserts, had so existed since the Creation.

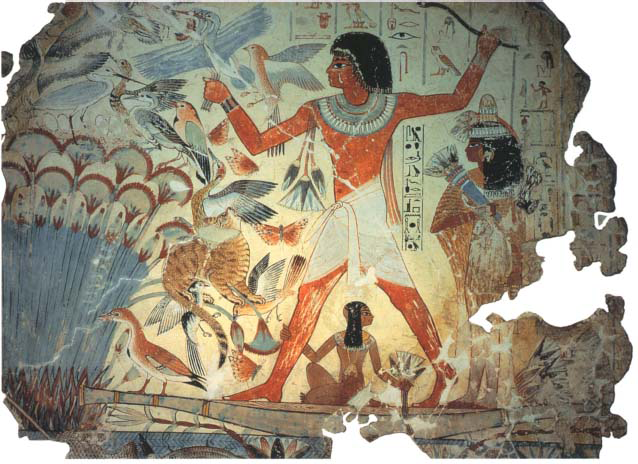

In fact neither assumption was correct: even Egypt and its people were subject to the slow transformations of time. At one time all Egypt, like most of Africa, was inhabitable. In the later part of the Middle Paleolithic Period, about 10,000 BC , there was an accelerating decline in local rainfall. The pastures and savannahs of the Egyptian plains became desert. Even as late as about 2350 BC , average rainfall in Egypt was much higher than today up to six inches a year but it was decreasing and continued to do so throughout historic times. Much of the country, therefore, became increasingly inhospitable to animals and men. The hippos, the gazelles, the buffaloes and ostriches gradually became fewer. Wild asses, wild cattle, ostriches and lions continued to be hunted well into the time of the pharaohs; Amenophis III boasted that in the first ten years of his reign ( c . 14131403 BC ) he had killed 102 lions with his own hand; and 200 years later, Ramesses III had carved onto the stone pylon of his temple at Medinet Habu the splendid panorama of a royal hunt for wild asses and bulls. There were, in fact, many hippos in the Nile delta even in Roman times. But, in general, the encroachment of the desert was inexorable, driving the fauna of the plains ever further to the south, and mankind to the desert oases and, above all, to the Nile valley.

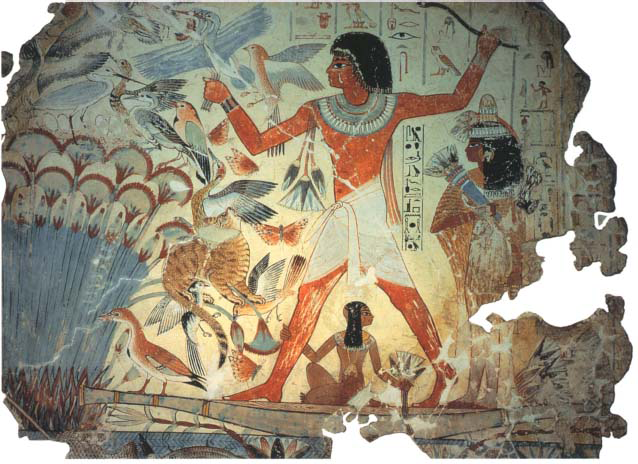

A fowling scene from the tomb of Nebamun, Thebes.

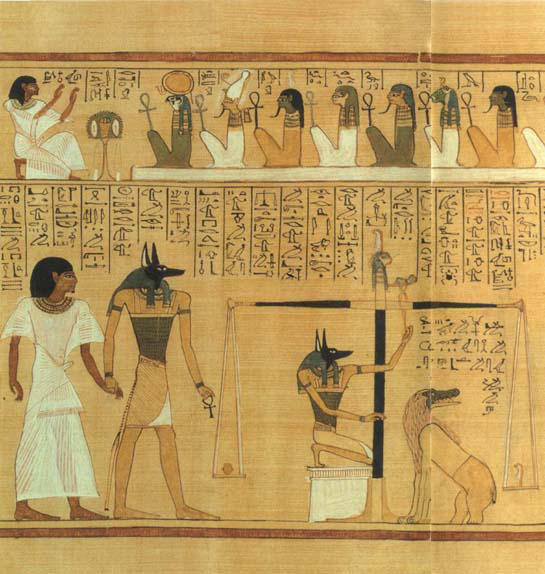

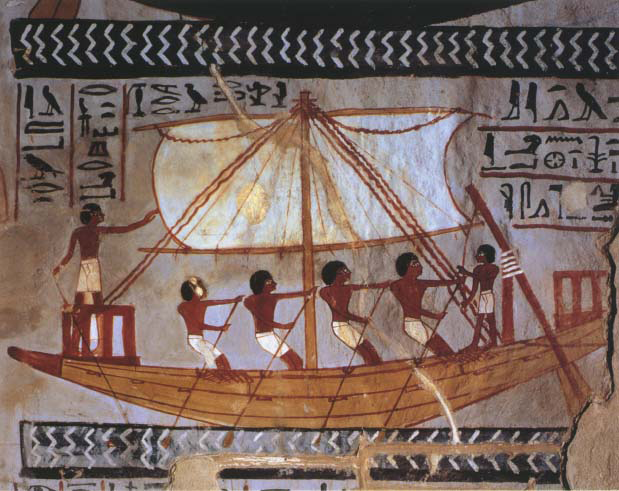

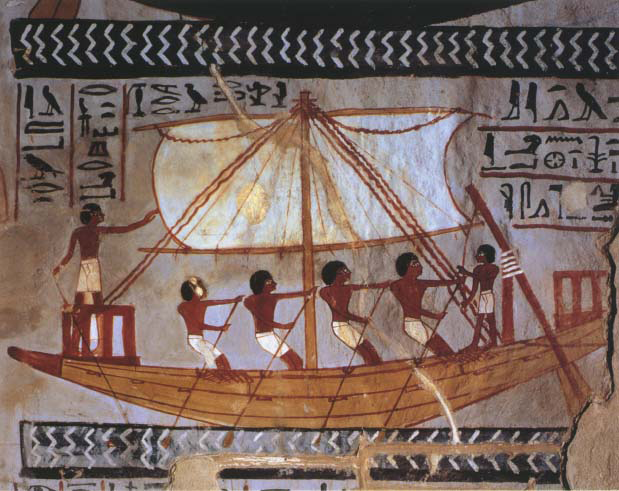

A river-boat steered by a stem-oar, from a fresco in the tomb of Sennufer at Thebes. Some Egyptian boats were built with the unsatisfactory wood of the sycamore.

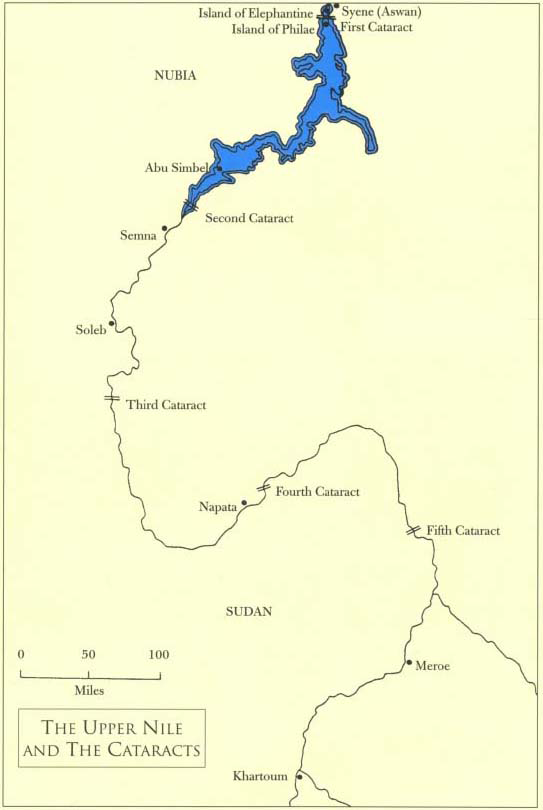

The Nile seems to have begun to assume its present course about 10,000 years ago. At the time when the plains were drying up, the rainfall of the African forests and the melting snows of Ethiopia were creating its annual flood and transforming the great river into a geographical constructor. It drove its way through the granite rocks to the south of the First Cataract, through the sandstone stretching almost as far north as ancient Thebes, and then through the limestone plateau to the Mediterranean Sea. At the sea itself, it piled up the alluvial delta, and in the series of terraces and valley bottom it carved out of the rocks, spread with the alluvial soil carried down with the flood, it created a continuous oasis 750 miles long from the First Cataract to the sea.

As the savannah turned into desert, palaeolithic man began to descend to the Nile terraces and then to the valley bottom. Of course the valley was initially marsh. For many millennia, the tract from the First Cataract to Thebes was a lake; and much of the delta remained marsh throughout our period. But potentially this was rich agricultural land 13,300 square miles in the valley itself, and a further 14,500 square miles in the delta. The Nile supplied not merely reliable water but equally reliable alluvial deposits and fertilization. By 5000 BC the palaeolithic hunters of the plains had transformed themselves into the neolithic farmers and herdsmen of the valley and delta, and the agricultural economics of historic Egypt had taken shape. What remained to be done was to complete the conquest of the marshland and to begin the harnessing of the river, by dyke, barrier, basin and canal and therein lies the story of the Egyptian State, and the culture it begot.

The Nile alluvium makes the soil black. From the very earliest times, the Egyptians divided their country into ke me, the black that is, the cultivable, inhabitable part and deshret, the red or desert. Such dualism seems to have been part of the Egyptian character. The country itself was seen as divided into two distinct halves: the Valley or Upper Egypt, and the Delta, or Lower Egypt; and the Delta in turn into a western, or Libyan, and an eastern, or Asian, half. The physical configuration of Egypt was completed by its external barriers: the cataracts cut if off to the south, the Libyan desert to the west, the Eastern Desert, the Red Sea and the Sinai Desert to the east, and the Delta, which with its marshes and myriad, ever-shifting channels, constituted as much an obstacle as an exit, to the north.

Thus isolated from the world beyond, Egypt was dominated by the seasonal rhythms of its river. Not only the river but the inundation itself, termed Hapy, was worshipped as divine. Hapy was bearded, with water-plants sprouting from his head, and with female breasts, symbolizing fertility, hanging from his body. The Egyptians believed that he drew his power, that is the waters of the flood, from underground basins around the First Cataract and long after this explanation had been shown to be false they worshipped the gods of this region fervently. And so they might, for the Nile is perhaps the most beneficent and dependable great river on earth. The conjunction of its two sources, the White and the Blue Nile, and its long journey through the plateau, give the annual flood the character of a reliable annual system rather than an unpredictable catastrophe.