Ramesses the Great

Ramesses the Great

Egypts King of Kings

Toby Wilkinson

ANCIENT LIVES

ANCIENT LIVES

Published with support from the Fund established in memory of Oliver Baty Cunningham, a distinguished graduate of the Class of 1917, Yale College, Captain, 15th United States Field Artillery, born in Chicago September 17, 1894, and killed while on active duty near Thiaucourt, France, September 17, 1918, the twenty-fourth anniversary of his birth.

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of William McKean Brown.

Copyright 2023 by Toby Wilkinson.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

.

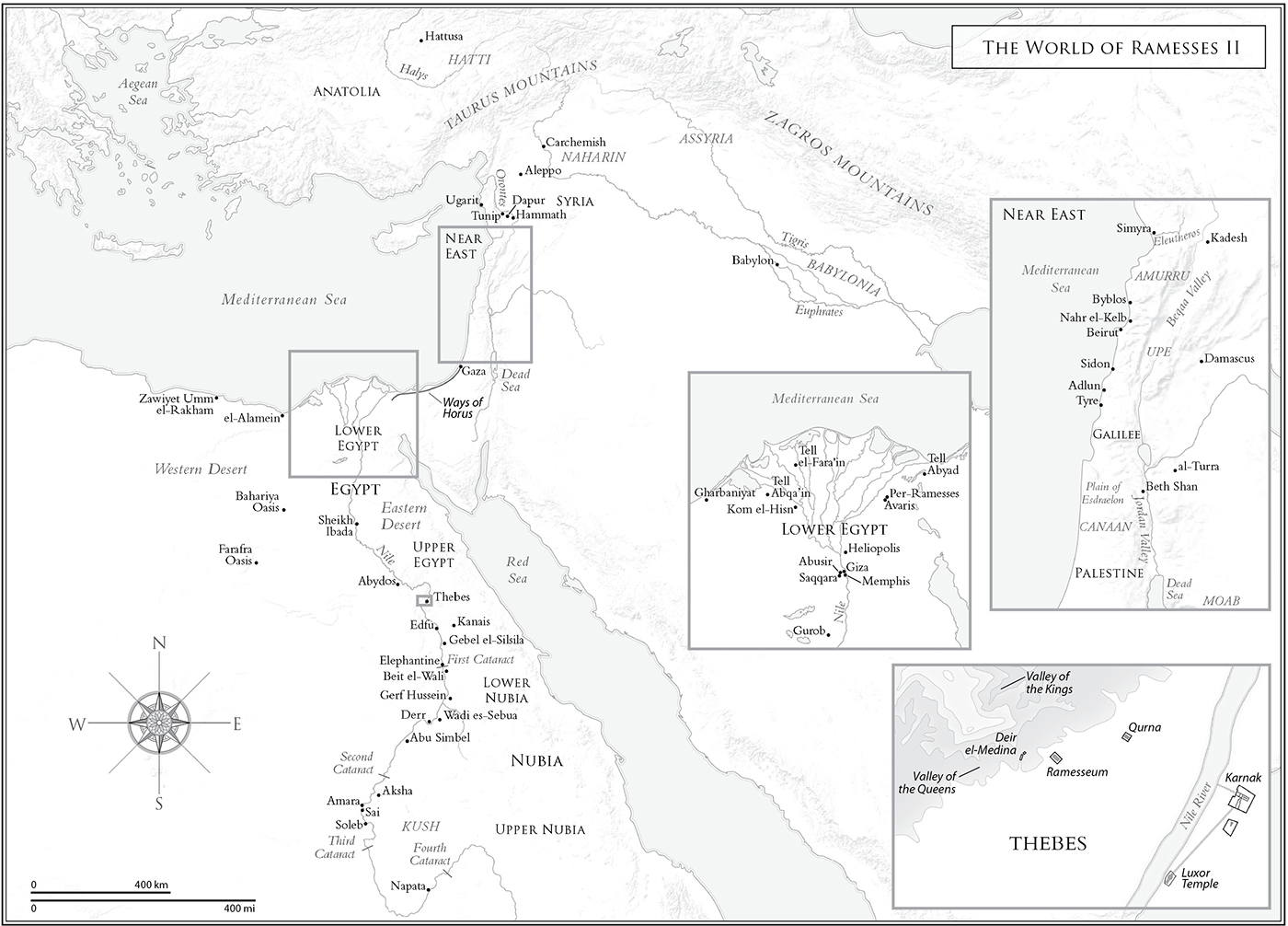

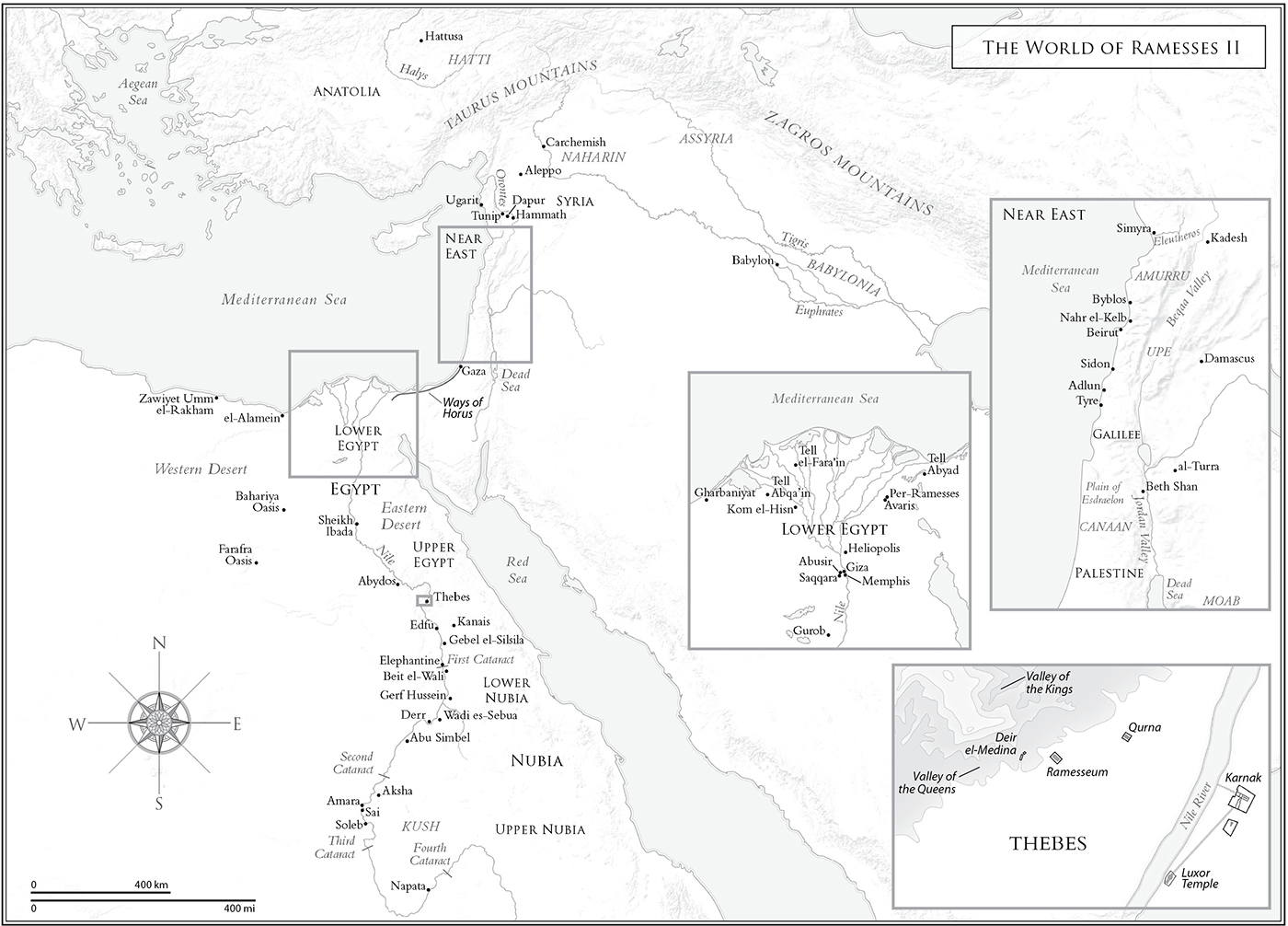

Map of the Battle of Kadesh by John Gilkes.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in the Yale typeface designed by Matthew Carter, and Louize, designed by Matthieu Cortat, by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022941449

ISBN 978-0-300-25665-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ANCIENT LIVES

ANCIENT LIVES

Ancient Lives unfolds the stories of thinkers, writers, kings, queens, conquerors, and politicians from all parts of the ancient world. Readers will come to know these figures in fully human dimensions, complete with foibles and flaws, and will see that the issues they facedpolitical conflicts, constraints based in gender or race, tensions between the private and public selfhave changed very little over the course of millennia.

James Romm

Series Editor

Contents

Ramesses the Great

Introduction

Of the hundreds of kings who ruled ancient Egypt over the twenty-six centuries between its foundation as a nation-state (c. 2950 B.C.) and its absorption into the Hellenistic world (332 B.C.), only one is accorded the epithet the Great by modern Egyptologists. Ramesses II, known to his contemporaries as Usermaatra and to later legend as Ozymandias, bestrode the Nile Valley, and the wider ancient Near East, like a colossus. Indeed, he left more monumentsusually adorned with immense statues of himselfthan any other pharaoh. He also sired more children, his sons and daughters numbering at least one hundred. His unusually long reign of sixty-six years and two months (12791213 B.C.) saw foes come and go, and three designated successors predecease their seemingly immortal father.

These are the bare facts of an exceptional life, yet they do not in themselves explain the particular prominence of Ramesses reputation, both in his own time and in every era since. Other pharaohs ruled over a larger empire, were more successful military leaders, achieved greater sophistication in art and architecture. As Ramesses, then, was not as exceptional as he might have wished to be. All kings of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with pomp and pageantry, veiled themselves in a cloak of divinity, and took great pains to project their name and status, both to shore up their current position and to secure their eternal reputation. What was it about Ramesses II that made him different, special, and noteworthy in the long line of pharaohs? That is the overarching question I seek to address in this book.

In an examination of the life and times of Ramesses the Great, several factors come to the fore. First was the age in which he lived. The period known to Egyptologists as the New Kingdom (15391069 B.C.) marked the peak of ancient Egypts power and prosperity. At the start of the New Kingdom, Egypts rulers threw off foreign occupation and, to ensure there could be no repeat, carved out an empire of their own in the Levant and Nubia. At its greatest extent, Egyptian-controlled territory stretched from central Syria in the north to the Fourth Nile Cataract in the south, a distance of over a thousand miles. As an imperial power, Egypt enjoyed unfettered access to the gold mines of Nubia, the trading networks of the Near East, and the ports of the eastern Mediterranean. By the time Ramesses acceded to the throne, the era of empire building had ended but the era of imperial grandeur was at its zenith. Under Ramesses, Egypt was richer and more powerful than it had ever been before, or would ever be again. As a consequence, he had access to greater resources than any of his predecessors or successors.

Second, Ramesses used his position as a great king (one of an exclusive club of Bronze Age rulers which also included the rulers of the Hittites, Babylonia, and Assyria) to project Egypts influence and secure itsand hiscontinued prominence. Although Ramesses came from a family of army generals and his dynasty was steeped in martial tradition, it was as a diplomatic strategist, not a military tactician, that he achieved his greatest successes. His armed campaigns generally ended in pyrrhic victories or stalemates, but they nevertheless served to maintain the status quo, giving Ramesses time to maneuver Egypt into a strong bargaining position. Previous rulers of the New Kingdom had been either invincible warriors or consummate diplomats; Ramesses was neither, but he was perhaps the first to employ both approaches in combination to navigate the shifting sands of Near Eastern politics to Egypts advantage.

In addition, Ramesses acted on a scale that few other pharaohs, before or after, could match. His monuments were more impressive, even if many of them were reused from earlier epochs. His immediate dynasty was more numerous, even if many of his children died young. (But such was the fate of most people in ancient Egypt.) Ramesses roles as builder and father were the most prominent means by which he sought to establish his monarchical and dynastic credentials.

Finally, in every facet of his reign, Ramesses seems to have been obsessed with his legitimacy and his legacy. This had much to do with the circumstances under which Ramesses royal line, termed by Egyptologists the nineteenth dynasty (12921190 B.C.), had come to power. His grandfather, after whom he was named, had started life as a commoner, and Ramesses was acutely conscious of his familys plebeian origins. One of his abiding preoccupations was therefore to assert his legitimacy by reference to the unbroken sequence of Egypts kings that stretched back to the dawn of history. At the same time, Ramesses wanted to be seen as the progenitor of his own dynasty and the founder of a new order. Hence, the character of his reign presents a complex amalgam of tradition and innovation. The result was a period of uncommonly rich cultural invention and expression.

When it came to usurping the statues of earlier rulerssomething Ramesses did with great enthusiasmhis strong preference was for the works of the twelfth and eighteenth dynasties, not just because they were especially well crafted, and especially large, but also because they epitomized the classical eras of the past and hence symbolized continuity. At the same time, Ramesses artists absorbed elements from the revolutionary style of an earlier reign (that of Akhenaten, the heretic pharaoh, who died just fifty-seven years before Ramesses accession), deploying the same naturalism and emotional sensitivity, albeit in a more traditional style. Under Ramesses patronage, the large-scale depiction of battle scenesperhaps his favorite artistic genrebroke free of the earlier system of rigid registers to flow across entire walls. In the field of literature, too, the shackles of tradition were thrown off, as new texts were composed for the first time in the modern spoken vernaculareven as the royal court and scribal training schools were showing a renewed interest in the classical writers of the past. And in religious matters, perhaps the most tradition-bound sphere of ancient Egyptian culture, the choice of texts for the decoration of Ramesses royal tomb demonstrated a fresh new direction.

Next page

ANCIENT LIVES

ANCIENT LIVES