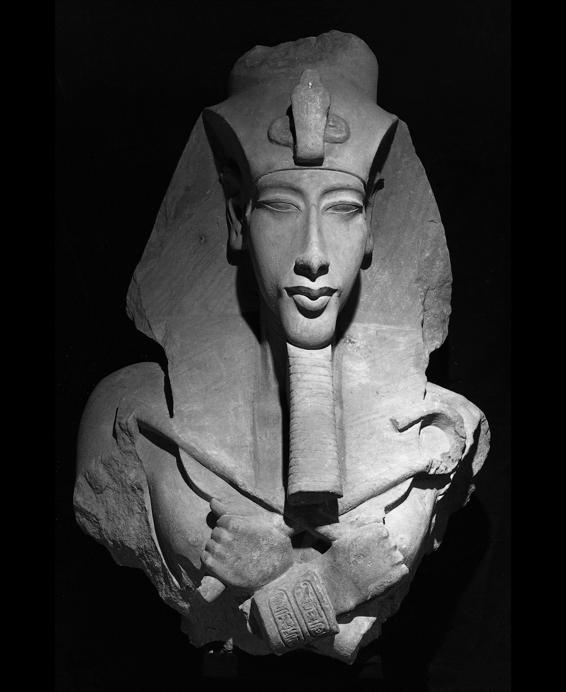

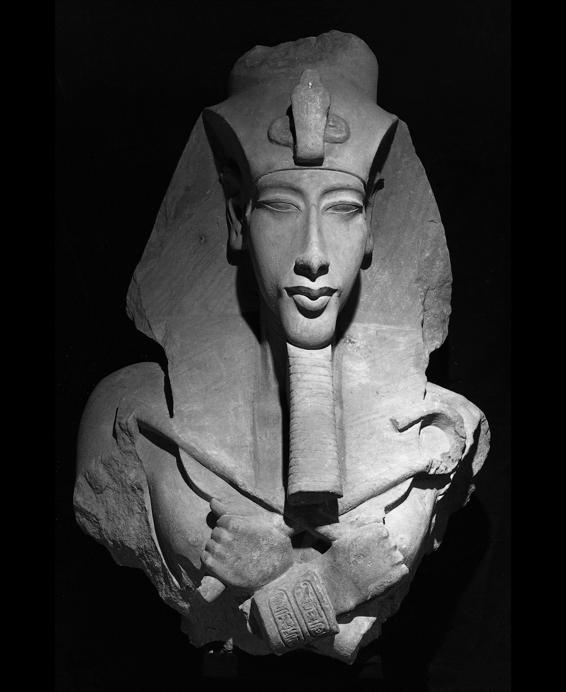

Colossal statue of Akhenaten, from Karnak

About the author

Nicholas Reeves is a renowned Egyptologist and one of the worlds leading experts on Ancient Egypt. Over the last 35 years he has curated Egyptian collections at the British Museum, Eton College and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, among others, and organized several major exhibitions. From 1998 to 2002 he was Director of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project in Egypts Valley of the Kings.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Searching for the Lost Tombs of Egypt

The Great Cities in History

The Great Empires of the Ancient World

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

Late Predynastic | c. 3100 BC |

Early Dynastic Period |

1st3rd Dynasties | 29202575 |

Old Kingdom |

4th8th Dynasties | 25752134 |

First Intermediate Period |

9th11th Dynasties | 21342040 |

Middle Kingdom |

11th14th Dynasties | 20401640 |

Second Intermediate Period |

15th17th Dynasties | 16401532 |

New Kingdom |

18th Dynasty Ahmose Amenophis I Tuthmosis I Tuthmosis II Tuthmosis III Hatshepsut Amenophis II Tuthmosis IV Amenophis III | 15501307 |

Amenophis IV-Akhenaten Smenkhkare Tutankhamun Ay Horemheb | 13531335 |

19th Dynasty including: Ramesses I Sethos I Ramesses II | 13071196 |

20th Dynasty | 11961070 |

Third Intermediate Period |

21st25th Dynasties | 1070712 |

Late Period |

25th Dynasty2nd Persian Period | 712332 |

Greco-Roman Period |

Macedonian DynastyRoman Emperors | 332 BCAD 395 |

Conventional chronology after J. Baines & J. Mlek, Atlas of Ancient Egypt (Oxford, 1980), .

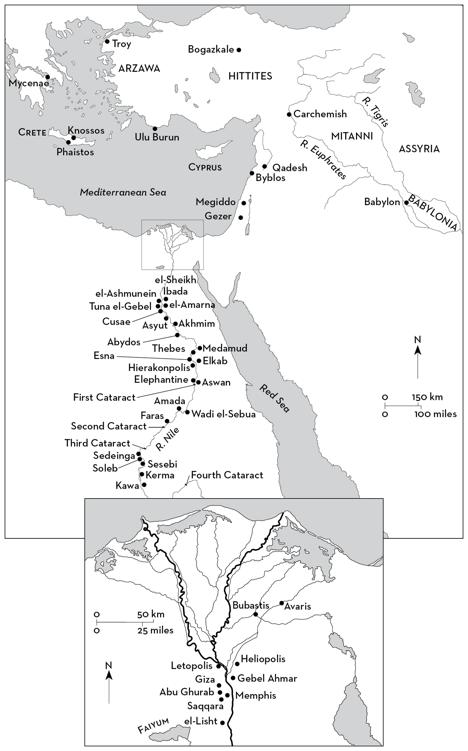

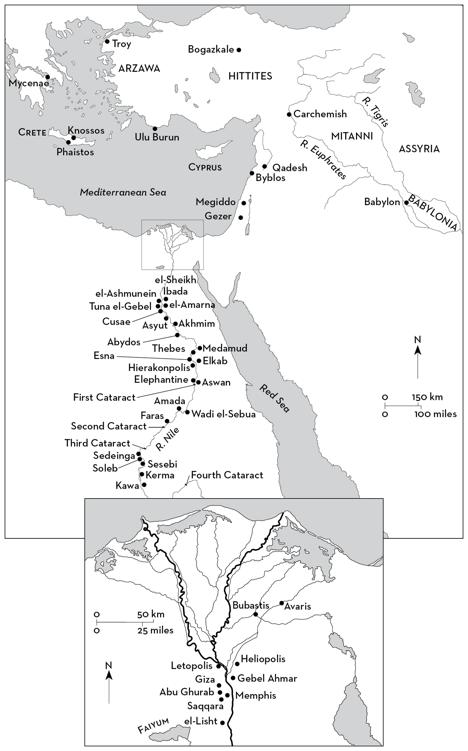

Map of Egypt and the Near East

at the name Akhnaton there emerges from the darkness a figure more clear than that of any other Pharaoh. For once we may look right into the mind of a king of Egypt and may see something of its workings ARTHUR WEIGALL

The setting for this book is Egypt, and the ruins of a city founded and abandoned more than three thousand years ago one and a half millennia before the birth of Christ, and some twenty centuries before the advent of the prophet Muhammad. The name given to this city in antiquity was Akhetaten, Horizon of the Aten; it is a site better known today as el-Amarna and it is the source for almost all we yet know of Egypts most intriguing king.

This king was Amenophis IV, more familiar to the modern world by his later name, Akhenaten. In the endless procession of Egypts pharaonic masters, Akhenaten stands alone. He looks different: his often freakish appearance in art elongated and effete is totally at odds with that of the traditional Egyptian ruler-hero. And he appears to have acted differently also most famously by his abandonment of Egypts traditional pantheon in favour of a single god, the Aten, or solar disc.

A younger son of the 18th-Dynasty pharaoh Amenophis III and his consort Tiye, prince Amenophis became heir with the unexpected death of an elder brother. Married early in life to the beautiful Nefertiti, the new king fathered six children all daughters; his only living son would be Tutankhamun, by a secondary wife named Kiya. A mystery woman, Kiya disappears soon after the birth, closely followed by Nefertiti herself at which point Akhenaten adopts an obscure co-ruler, Nefernefruaten/Smenkhkare, to share his throne. Akhenatens co-regent is succeeded in turn by Tutankhamun and then by the gods father Ay, with whom the greater Amarna period draws to a final close. It was an era which, though starting off well enough, degenerated rapidly into mayhem and widespread religious persecution, an orgy of wanton destruction and almost total economic collapse. For the events he set in train, Akhenaten could never be forgiven: with a ruthlessness not seen in Egypt before or since, Amarna, both as a city and a concept, was razed and all trace of pharaohs existence systematically expunged.

What manner of man was Atens first prophet? Because of his religious reforms, Akhenaten has for long struck a chord in todays predominantly monotheistic world; and the fact that pharaohs revolution ultimately failed has seemed only to confirm his role as an early revealer of religious truth a power for good. Such a spin, promoted almost a century ago by James Henry Breasted and Arthur Weigall and eagerly taken up by scholars and general public alike, is certainly wrong, and now beginning to give way to darker visions. As prophets go, it seems clear that Akhenaten was a false one, and working very much in his own political interest.

One early critic of Amarna historiography was the American anthropologist Leslie A. White: Only where one knows so little can one write so much, he despondently remarked in an article written in 1948; the absence of facts gives the imagination free reign. It would be idle to claim that imagination plays no part in the pages which follow; inevitably it does. I trust, however, that it is an imagination checked by critical scrutiny of the available sources and balanced by considerations of historical precedent and probability. For the real problem with Amarna is not so much a shortage of good evidence as a superabundance of speculation misrepresented as fact. Readers must decide for themselves how successful I have been in separating the wheat from the chaff and how convincing the result.

I close this preface with a quote from John Pendlebury, who wrote his own book on el-Amarna in 1935:

highly theoretical it does seem to me to fit the facts as we know them at present. Based as it is mainly on the results of excavation, [however,] where even a broken ring bezel may be a piece of evidence of the first order, it may easily be modified or even flatly contradicted by future discoveries .

If the picture I paint differs markedly from that of Pendlebury and others, in this respect, at least, the situation remains the same.

Nicholas Reeves

The year is 1887, the place an expanse of sanded-up ruins on the east bank of the Egyptian river Nile, a short distance from the modern village of el-Till. The sky shines a clear, deep blue, dominated by a relentless sun; beneath its rays a peasant woman is occupied patiently digging

Next page