MOSES

AND

AKHENATEN

The Secret History of Egypt

at the Time of the Exodus

AHMED OSMAN

Bear & Company

Rochester, Vermont

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A NUMBER of people have given their help and support to the preparation of this book. I should like to thank in particular Dr Eric Uphill, Honorary Research Fellow in Egyptology at University College, London, for reading the manuscript and for his valuable advice and suggestions; the French archaeologist Professor Jean Yoyotte for discussing the time of the Exodus and the location of Zarw; the French archaeologist Professor Alain-Pierre Zivie for giving details of his recent discoveries, as yet unpublished, in the tomb of Aper-El at Sakkara; Professor Younes A. Ekbatrik, the Egyptian Cultural Counsellor in London, for arranging a discussion about the fortified city recently found at Tell el-Heboua, East Kantarah, and its possible identification with Pi-Ramses; my friend Gerald OFarrel for his support; Cairo Museum and its director, Mohammed Mohsen, for providing, and allowing the use of, many of the photographs to be found in this volume, and, finally, H. J. Weaver for his assistance in editing the material and making it less complex than it might otherwise have been.

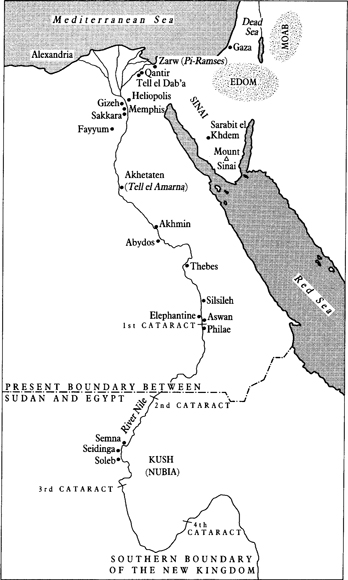

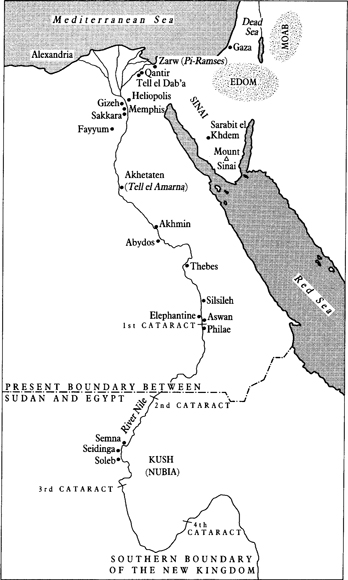

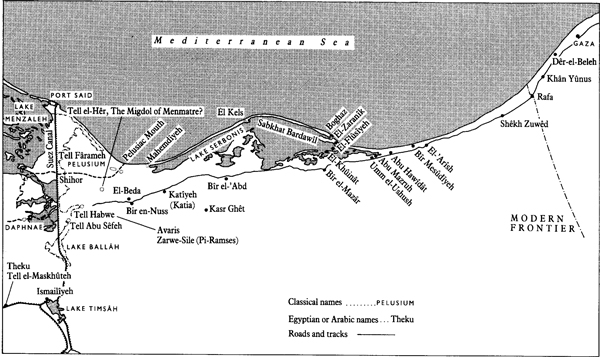

Map of Egypt during the time of the Empire, 16th 12th centuries BC

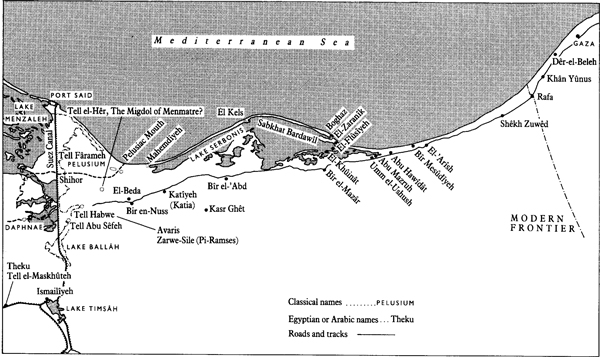

The Ways of Horus, the ancient road (mentioned in the Bible) between Egypt and Palestine in northern Sinai

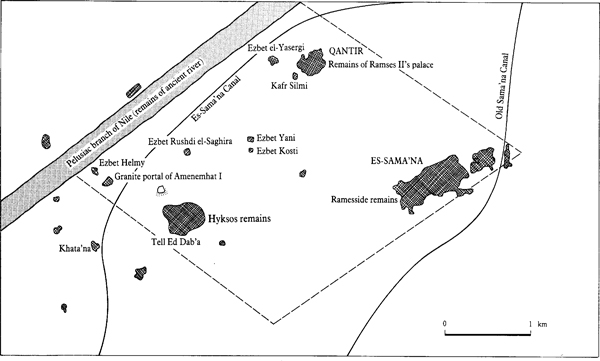

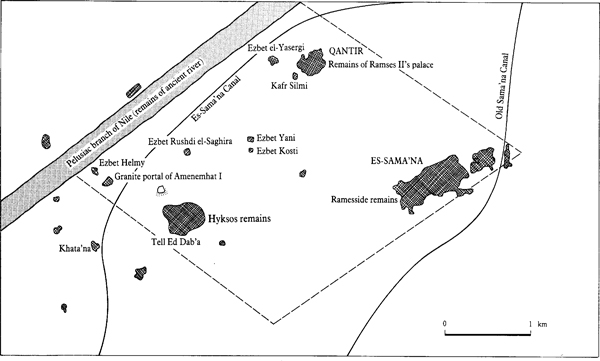

Map indicating the artificial borders of the location hitherto accepted for Pi Ramses/Avaris.

As can be seen, there are no archaeological connections between the different ancient sites

PREFACE

I CAME to London from Cairo a quarter of a century ago, intending to devote most of my time to trying to establish links between the Bible and what we know, from a variety of sources, of Egyptian history. The choice of London was dictated by the far superior research facilities to be found there.

Initially, while earning a living by teaching Arabic, I embarked on a course of intensive study. I enrolled in the Egypt Exploration Society and spent six years familiarizing myself with the ancient history of my country and mastering hieroglyphics. I also learned Hebrew and studied the Bible.

However, when I tried to put this knowledge to use I found myself facing the same problem that had baffled scholars for more than a century establishing a starting point by identifying a major biblical figure as a major figure in Egyptian history. Who was Joseph, the Patriarch who brought the tribe of Israel down to Egypt from Canaan? Who was the unnamed Pharaoh who appointed him as a senior minister, the virtual ruler of the country in the kings name? Who was Moses? If, as I believed, the Old Testament was fundamentally a historical work, the characters who appear in its stories had to match characters in Egyptian history.

It was another fifteen years before I stumbled upon the vital clue (in what seems in retrospect a moment of inspiration) embedded in a biblical text so familiar that I found it hard to believe that its significance had not struck me years earlier. The passage in question occurs in the Book of Genesis. The brothers of the Patriarch Joseph, we are told, had sold him into slavery in Egypt where, as a result of interpreting Pharaohs dream about the seven good years that would be followed by seven lean years, he was appointed the kings senior minister. The brothers later paid two visits to Egypt at times of famine in Canaan. On the second occasion, Joseph revealed his identity to them, but told them reassuringly that they should not blame themselves for having sold him into slavery because it was not they who had sent him hither, but God; and he hath made me a father to Pharaoh (Gen. 45:8).

A father to Pharaoh! I thought at once and, as I have said, could not understand why I had not made the connection before of Yuya, minister to two rulers of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Although Yuya was not apparently of royal blood, his tomb had been found in the Valley of the Kings in 1905. Little attention was devoted to him because he was considered comparatively unimportant. Yet Yuya is the only person in whose tomb the title it ntr n nb tawi holy father of the Lord of the Two Lands, Pharaohs formal title has been found. It occurs once on one of his ushabti (royal funeral statuette No. 51028 in the Cairo Museum catalogue) and more than twenty times on his funerary papyrus.

Could Joseph and Yuya be the same person? The case for this being so is argued in my first book, Stranger in the Valley of the Kings. Once this link was established, all manner of things began to fall into place:

It became possible to create matching chronologies from Abraham to Moses on the one hand, and from Tuthmosis III, the sixth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty, to Seti I, the second ruler of the Nineteenth Dynasty, on the other.

It also became clear that:

Of the three periods of time given in the Old Testament four generations, 400 years and 430 years for the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt, four generations is correct, a view which Jewish scholars have arrived at by another reckoning;

As it is known that the Israelites were in Egypt at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty and beginning of the Nineteenth, the Descent must have taken place more than two centuries later than most scholars believed, which explains why their efforts to match biblical figures with Egyptian figures has been so protracted; they focused their quest on the wrong era;

The four Amarna kings Akhenaten, Semenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Aye who ruled during a tumultuous period of Egyptian history when an attempt was made to replace the countrys multitude of ancient gods with a monotheistic God, were all descendants of Joseph the Patriarch;

The Exodus was preceded by the ending of Amarna rule by Horemheb, the last king of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

This book is an attempt to take further the story told in Stranger in the Valley of the Kings by demonstrating that Moses is to be regarded as the Pharaoh Akhenaten.

INTRODUCTION

IN August 1799, while French troops were repairing fortifications to the north of Rasheed on the left bank of the Nile, thirty miles east of Alexandria an officer engaged in demolishing an ancient wall struck a black stone with his pick. The stone, thought to have formed part of a temple in earlier times, proved to bear three inscriptions. At the top were fourteen lines of hieroglyphs; in the centre thirty-two lines of demotic, the simplified form of Ancient Egyptian writing; and, at the bottom, fifty-four lines of Greek. The Greek text was translated and published, but the real importance of the Rosetta Stone, as it was called from the European name of the place where it was found, did not emerge until 1818. Then Thomas Young (17731829), a British physician, scientist and philologist, succeeded in deciphering the name of Ptolemy in the hieroglyphic section and in assigning the correct phonetic value to most of the hieroglyphs. Although the British scholar took the first steps, the final decoding of the stone was done three years later by a brilliant young French philologist, Franois Champollion (17901832).

With his new-found knowledge Champollion was able to translate some Egyptian texts that had until that time been a complete mystery to historians. Among them were the cartouches of the king-list on the walls of the Osiris temple at Abydos in Upper Egypt. The list, which included the names of the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty, made no mention of Akhenaten or the other three Amarna kings Semenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Aye who followed him. In the circumstances it is not surprising that when, in the middle of the last century, archaeologists came across the strangely-drawn figure of Akhenaten in the ruins of Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt they were not sure initially what to make of him. Some thought that, like Queen Hatshepsut, this newly discovered Pharaoh was a woman who disguised herself as a king. Further cause for conjecture arose from the fact that Akhenaten had ascended to the throne as Amenhotep IV and later changed his name. Were they dealing with one Pharaoh or two?

Next page