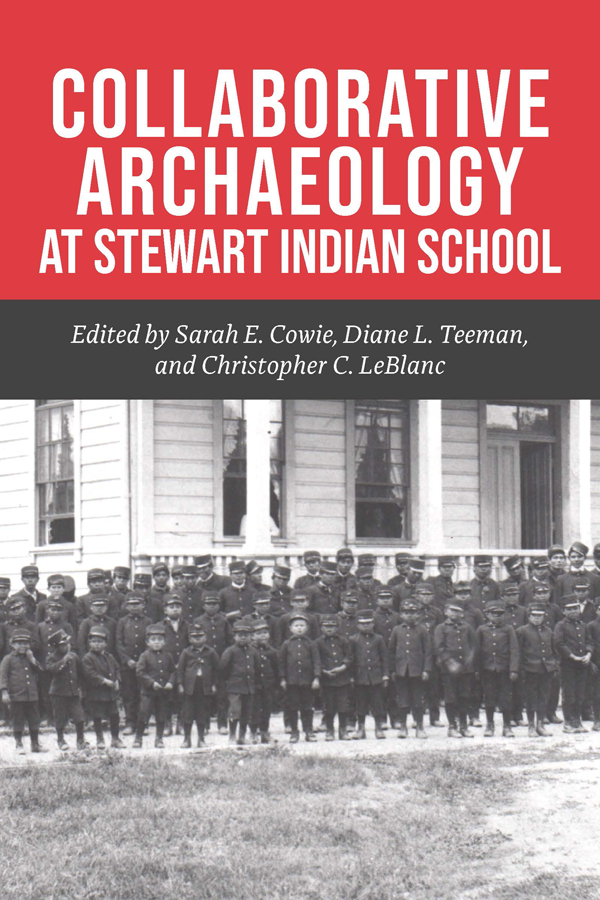

Sarah E. Cowie - Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School

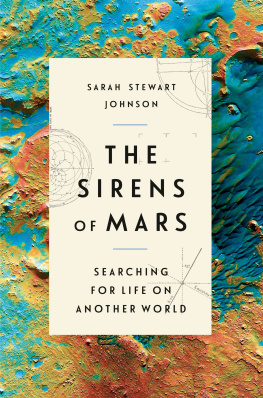

Here you can read online Sarah E. Cowie - Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses), genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School

- Author:

- Publisher:Chicago Distribution Center (CDC Presses)

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First and foremost, the editors, authors, and everyone associated with this project acknowledge and give thanks and respect to the children of the Stewart Indian School. It is an honor to dedicate this volume to them. Special thanks to all the alumni and community members who visited the excavation and shared their stories of this important place. The editors would also like to thank everyone at the Nevada Indian Commission and its Stewart Advisory Committee, especially Sherry L. Rupert and Chris A. Gibbons, for their partnership in the project, assisting in all of the developmental procedures, and, of course, for providing the opportunity to collaborate with tribal members on an archaeological field school. Also, we are grateful to the Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office, especially Darrel Cruz, the Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, for his significant contribution to the project as a research partner and stakeholder. Richard Arnold, Chair of the Nevada Indian Commission, gave an influential talk at the field school and provided considerable advice on the interpretations of faunal remains, which became a significant component to the interpretations discussed in this volume. We would also like to extend heartfelt thanks to the late Albert Phoenix, tribal elder from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, for his blessing of the participants during the field school. Thanks also to the late William Oliver who shared his knowledge of the Stewart Indian Schools history. Thanks to Terri McBride for volunteering on the project, helping us connect with each other, and sharing her extensive knowledge of collaborative archaeology and the Stewart Indian School.

We are also grateful to Dr. Debra Harry, member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, for her excellent presentation on informed consent and research involving Indigenous peoples during the field school. Her discussion of decolonizing methodologies inspired us to research those issues more thoroughly and to eventually focus this volume on such methods in archaeology. The authors would also like to express gratitude to Jo Ann Nevers, Washoe tribal elder and historian, and alumnus of Stewart Indian School, for a talk on her personal experiences living at the school, and what life was like for Washoe tribal members before and after contact with Europeans. Thanks also to Larry Hale, tribal member and retired Stewart Facility Supervisor, and to Ron Bodnar, current Stewart Facility Supervisor, for providing the rare, original campus maps that provided invaluable information on the location of historic buildings on campus.

Ron James, former State Historic Preservation Officer, and Rebecca L. Palmer, current State Historic Preservation Officer, provided advice and guidance in obtaining permissions for the site. Thanks also to Ron James for his visit to the field school and presentation on the archaeological history of the site. Thanks to Gene Hattori of the Nevada State Museum for giving guidance on the excavation, and on working with regional tribes.

Additionally, we thank all of the wonderful students and volunteers who participated in the 2013 field school: Amy Balagna; Patrick Burtt, a Washoe tribal member; Delaney Childs; Eric DeSoto, a Fallon Paiute-Shoshone tribal member; Callie Greenhaw; Charles Hutcheson; Dania Jordan; Jessica Leonard; Lonnie Teeman, a Burns Paiute tribal member; and Nick Teipner.

Thanks also to the many volunteers who aided in the cleaning, cataloging, and analysis of artifacts after the field school: Ashley Atwood, Amy Balagna, Lisa Ena, Robert Furlong, James LeFleur, Leona Novio, Austin Offenbacher, Samantha Redman, and Cavin VanGeem. Special thanks must go to Robert Leavitt and Lisa Machado, who both provided vital assistance during this process. Also, Dania Jordan and Rose Matschke worked many hours during all of the cleaning, cataloging, and analysis of artifacts. Callie Greenhaw and Eric Terzich helped create figures for the volume. Ashley Younie and Evan Pellegrini conducted the faunal analysis, and Ian Springer analyzed wood and soil samples.

Special thanks go to the late Mark Johnson, a Washoe and Paiute tribal member of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, who volunteered on the project, shared his experiences as an archaeological technician, and gave us some of our most important lessons on spirituality and respectful protocols. We are also grateful to A. J. Johnson, who joined this project in 2018, for his kindness and support of our efforts to honor the memory of his late brother Mark Johnson, as well as sharing his own important stories of attending Stewart as a student and later working as an archaeological technician. Thanks also to Amanda Hartman for introducing us to A. J. Johnson; we appreciate the many good things that come from collegial heritage networks. The editors are also grateful for the many participants in this project who thoughtfully contributed their knowledge and experiences in writing essays for this volume, making possible our shared goals for multivocality.

We are also grateful to Justin Race for his encouragement and support of publishing our multivocal approach. Two anonymous peer-reviewers provided excellent feedback that much improved the manuscript and offered welcome encouragement. Patrick Burtt, Ashley Long, and Daniel Montero provided editorial assistance in finalizing the manuscript, contributors essays, and figures. Luke Torn and Cindy Coan of University of Nevada Press provided copyediting and indexing that was much appreciated. We appreciate Alrica Goldstein, the Editorial, Design, and Production Manager at the University of Nevada Press, for moving the manuscript toward completion.

The research reported here was funded under grant awards entitled Governmentality and Social Capital in Tribal/Federal Relations Regarding Heritage Consultation (#W911NF1210205 and #W911NF1610150) from the U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory (ARO/ARL), Young Investigator Program (YIP), and Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE). The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the ARO/ARL. We are grateful to Dr. Lisa Troyer and Dr. Stephen Lee at ARO for supporting high-risk research in social science, and for recognizing archaeologys potential to help modern societies.

Any errors or oversights are the responsibility of the editors. We are grateful to everyone for contributing their insights and knowledge to this project, and we hope to do right by them in this volume.

Sarah E. Cowie, Diane L. Teeman, Christopher C. LeBlanc, Terri McBride, and Ashley M. Long

The woman who initially reprimanded us began to weep as she told us her story. We were in the midst of a collaborative archaeological field school at the site of Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada, with a great deal of involvement from tribal members from multiple tribes, many of whom had members that passed through Stewart, as this alumna had, during its complicated ninety-year history as an off-reservation boarding school in Nevada. Like many other alumni and community members, she had heard about our widely advertised project and was visiting Stewart, as many alumni do on a semiregular basis, to reconnect with the place and the memories associated with it. She had been shouting at us from a distance as she passed by, saying that we didnt know what we were getting into with excavating this place, that terrible things had happened here, and that we should leave such things alone. This is a common sentiment among many American Indians about archaeology in general, that things left by people in the past are too powerful to tamper with, especially things associated with negative experiences. Most people that talked to us about the project were either supportive or curious, but occasionally someone expressed concern. One tribes attorney contacted us, concerned that we might excavate graves of children who had died at the school, assuming that digging up graves was archaeologists primary occupation. On each of these interactions we had the opportunity to learn more about the school and what it meant to alumni, their families, and their tribes, as well as the history of the federal governments attempt to forcibly assimilate Native Americans. We also had the opportunity to do better archaeology through public involvement, train students in a multivocal and collaborativeapproach to archaeological field methods, and demonstrate that archaeologists are not always grave robbers.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

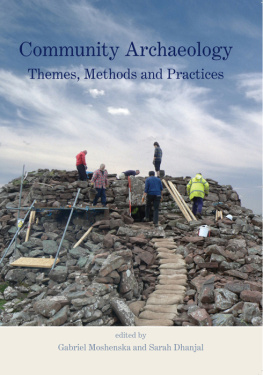

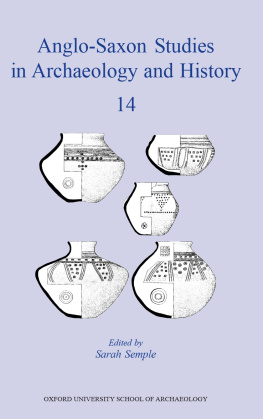

Similar books «Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School»

Look at similar books to Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.