ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Most of this book was written during the pandemic year, and so my most sincere acknowledgments are to those I met long, long before the virus wreaked such havoc on our lives and culture. Many have passed onDonald Richie, Kazuko Shibata, Kashiko Kawakita, John Gillett, Glenn and Kikuko Iretonbut without their mentorship, this book might not have come to light. I also want to thank Teruyo Nogami, that fount of information concerning Kurosawa, and Marty Gross, who facilitated many of my meetings in Tokyo and who has himself done so much to promote a better understanding of Japanese pottery-making techniques. I should also recognize the friendly counsel of David Streiff, who arranged retrospectives of both Naruse and Kinoshita during his time as director of the Locarno Film Festival.

A nod of gratitude, also, to my friends at Criterion in New York, in particular Kim Hendrickson and Fumiko Takagi. Thanks to the Criterion Channel, I was able to review more than a hundred Japanese classics in pristine condition. In addition, Im happy to have among my friends David Bordwell and Mark Le Fanu, authorities on Ozu and Mizoguchi respectively. My wife, Franoise, has accompanied me throughout much of this personal journey and shared my enthusiasm for Japanese culture and cookery.

Finally, my thanks to Peter Goodman, at Stone Bridge Press, who believed in this project. An author always cherishes publishers of this caliber. My editor at Stone Bridge, John Sockolov, and the director of publicity, Michael Palmer, also have proved indispensable in the creation and publication of this book.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abe, Kobo. The Woman in the Dunes. Translated by David Mitchell. London: Penguin Modern Classics, 1964.

Alpert, Steve. Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2020.

Bergman, Ingmar. Images: My Life in Film. London: Faber and Faber, 1995.

Bock, Audie. Japanese Film Directors. Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International, 1978.

. Mikio Naruse. Locarno, Switzerland: Editions du Festival International du film de Locarno, 1983.

Bordwell, David. Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

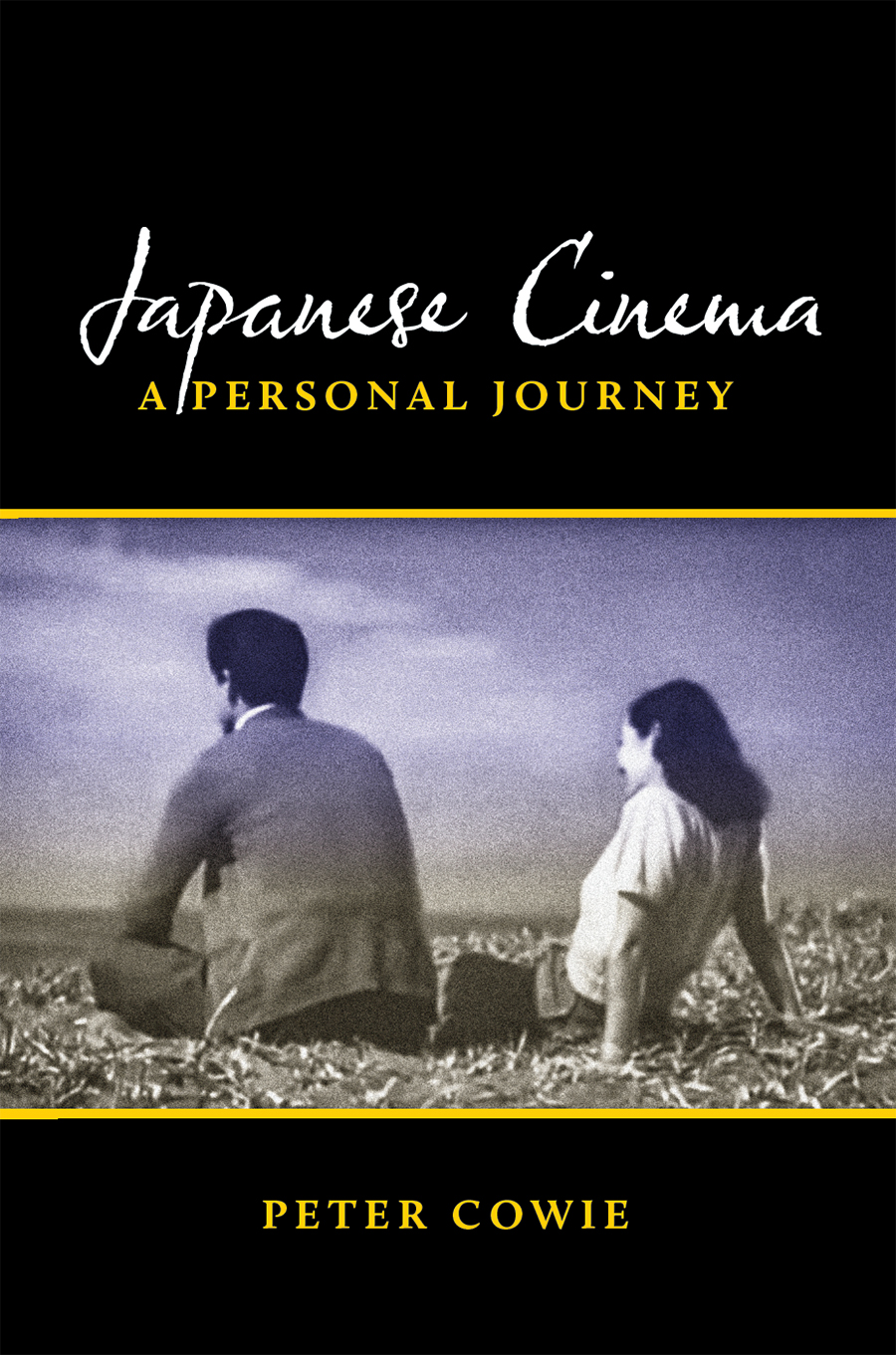

Cowie, Peter. Akira Kurosawa, Master of Cinema. New York: Rizzoli, 2010.

Iyer, Pico. Autumn Light: Japans Season of Fire and Farewells. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

Kawabata, Yasunari. Dandelions. Translated by Michael Emmerich. New York: New Directions Books, 2017.

Kinoshita. Locarno, Switzerland: Editions du Festival International du film de Locarno, 1986.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like an Autobiography. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.

Le Fanu, Mark. Mizoguchi and Japan. London: British Film Institute, 2005.

Misek, Richard. Chromatic Cinema: A History of Screen Color. London: John Wiley, 2010.

Mizubayashi, Akira. Petit loge de lerrance. Paris: Editions Gallimard, 2014.

Nathan, John. Modern Japans Greatest Novelist. New York: Columbia University Press, 2018.

Natsume, Soseki. Kokoro. Translated by Edwin McClellan. Tokyo and Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1969.

Nitob, Inazo. Bushido: The Soul of Japan. Sweden: Wisehouse Publishing, 2020; first published in 1900.

Nogami, Teruyo. Waiting on the Weather. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2006.

Ozu, Yasujiro. Carnets 19331963. Paris: Carlotta, 2020; first published in 1996.

Richie, Donald. The Inland Sea. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2015; first published in 1971.

. Japanese Portraits. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2006.

. Ozu: His Life and Films. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Sansom, George. A History of Japan to 1334. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958.

. A History of Japan, 13341615. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961.

. A History of Japan, 16151867. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1963.

Sato, Tadao. Le Cinma japonais 1. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997.

. Le Cinma japonais 2. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1999.

Tucker, Richard N. Japan: Film Image. London: Studio Vista, 1973.

1

The Samurai World

Akira Kurosawa

My enthusiasm for the work of Akira Kurosawa has its roots in my early youth, spent in the bucolic depths of Gloucestershire, in the west of England. My parents would take me to see Westerns like Shane and Bend of the River, and every so often we would visit the circus in some nearby town. From the Western, my favorite film genre, I assimilated a certain kind of morality. And from the circus stemmed my affection for clowns, enabling me to identify with the zany antics of Tahei and Matashichi in The Hidden Fortress, and of course Toshiro Mifune in his lighter, rump-scratching, rip-snorting moments in Seven Samurai.

In my undergraduate years at Cambridge University, I reveled in the opportunity to discover the profusion of films that reached the Arts Cinema in the center of town. Looking back through the reviews I wrote during that period (195962), I find that almost every week brought some revelationworks by Bergman, Antonioni, Resnais, Satyajit Ray, Fellini, Visconti, and, among Japanese directors, Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. Ozus lone masterpiece, Tokyo Story, shone like a lighthouse, and we had at that time scant knowledge of his scores of other films. Mizoguchis Ugetsu was screened at Londons Academy Cinema, and the Cambridge University Film Society even found a battered 16 mm print of Kurosawas Those Who Tread on the Tigers Tail, which I praised in Varsity, the campus newspaper: a jewel of a film that gently parodied the Kabuki period drama, with its extravagant facial expressions, its stylized gestures, and its bizarrely-dressed players.

I encountered Kurosawa at the Indian Film Festival in New Delhi, in 1977. We exchanged a few words at a reception, where Kurosawa felt, and seemed, out of place. We were the same height (six feet two or so), but even in a brightly lit room his eyes were hidden behind dark glasses as though he wished to discourage conversation. Impassive, Kurosawa would relax the following day when we strolled around the Taj Mahal with Michelangelo Antonioni and Satyajit Ray. His films revealed a persona infinitely more sensitive than his forbidding mien suggested. Beneath the sound and fury of Seven Samurai or Kagemusha dwelt a troubled soul rich in compassion for fellow human beings. In this respect, Kurosawa reminds one of Beethovenan artist driven to express his dreams and aspirations while at the same time seeking fresh ways of shaping those concerns. Action becomes a way of exploring life, whether it be a traveling shot in the forest in Rashomon, or hectic dancing in a nightclub during Ikiru. A medieval castle looming in the mist signifies as much to Kurosawa as an image of smokestacks in Tokyo does to Ozu.

Many decades after meeting Kurosawa, while researching my book on his work for Rizzoli, I sought out the Ishihara ryokan in central Kyoto. During the final period of his career, Kurosawa stayed at this haven of tranquility in order to work on his next screenplay, writing at a plain white table provided by the ryokan. Yasujiro Ozu, Kurosawas senior by ten years, also enjoyed writing in a ryokan, the Chigasaki in the Shonan Bay area southwest of Tokyo. Like Ozu, Kurosawa relaxed most while drinking with close colleagues, and Ishihara-san told me that postprandial sessions would continue in Kurosawas suite until as late as 2 a.m.

Next page