Table of Contents

1. !

2. |

WHAT IS JAPANESE CINEMA?

WHAT IS JAPANESE CINEMA?

A HISTORY

YOMOTA INUHIKO

TRANSLATED

BY PHILIP KAFFEN

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Yomota Inuhiko

English translation 2019 Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54948-6

Originally published in the Japanese as Nihon eigashi 110 nen (Tokyo: Shueisha, 2014).

English translation rights arranged with Yomota Inuhiko through the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Yomota, Inuhiko, 1953 author. | Kaffen, Philip, translator.

Title: What is Japanese cinema?: a history / Yomota Inuhiko; translated by Philip Kaffen.

Other titles: Nihon eigashi 100-nen. English

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2019] | Originally published in the Japanese as Nihon eigashi 110 nen (Tokyo: Shueisha, 2014). | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018054005| ISBN 9780231191623 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231191630 (paperback: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231549486 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesJapanHistory.

Classification: LCC PN1993.5.J3 N542513 2019 | DDC 791.430952dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018054005

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

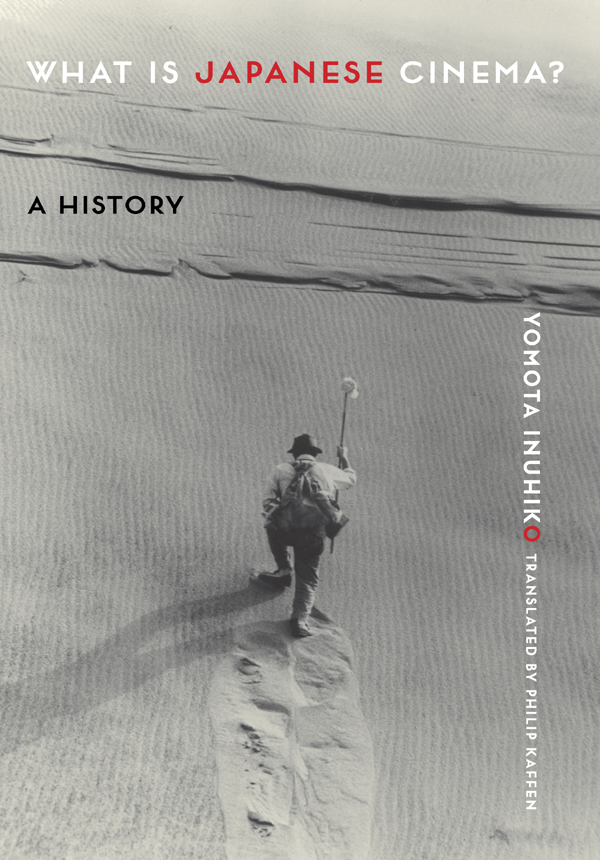

Cover design: Chang Jae Lee

Cover image: Teshigahara Hiroshi, Woman in the Dunes, 1964. Sogetsu Foundation

In memory of Kuzui Kinshir (19252014)

CONTENTS

N ames are in the Japanese order with family name first. Film titles are a bit problematic, but to the extent possible, the English translation of the title has been provided with the original Japanese title in parenthesis. In cases in which a standard translated title has remained fixed or an official release title exists, that is the title that will be used (e.g., The Life of Oharu for Saikaku ichidai onna). When no official release title and no standard translation exist, an approximation of the Japanese has been used. On occasion, if a film has become famous outside Japan under its original title (e.g., Ikiru), that will be the sole title, although generally an indication of what the title means is provided. In recent years, many Japanese titles have been given in English either written with the alphabet or transliterated phonetically into Japanese. In cases in which an English title but no Japanese title is given, this probably is the case.

S amurai. Godzilla. The life of a traditional Japanese family unfolding in tatami-mat rooms. The brute violence of yakuza films and the pure shjo girls of anime. For most film lovers in English-speaking areas this is the image of Japanese cinema.

This view isnt wrong. These are certainly essential elements of Japanese cinema. This book, however, was written for people who want to know the ways in which these elements are related to one another or who have an intellectual interest in the deeper world hidden in the background. It is the tale of how the Japanese people took an optical machine originally invented in the Westthe cinematographand made it their own, absorbing it and utilizing it to create a distinctive culture. In other words, it is none other than the story of modernity in Japan.

When encountering a work of art, you must always be wary of a certain trap. That is the temptation to praise a work before really understanding it. I hope that readers will come to see that behind any film they have watched and enjoyed there is a huge accumulation of culture and that no single work is complete in itself but always emerges as part of a chain of relationships to history.

Japanese cinema is made up of two words: Japanese and cinema. For those who are interested in Japanese cinema, the choice of which of those words to emphasize makes a big difference in the direction of their explorations.

Those who prioritize cinema will put all filmmakerswhether Kurosawa Akira, D. W. Griffiths, Jean-Luc Godard, Charlie Chaplin, or Steven Spielbergon one horizontal plane. The history of Japanese cinema is but a portion of the history of world cinema. That Kurosawa is Japanese is merely incidental and what is significant is the extent to which his works contribute to the expansion of the global language of technical images. A person who loves cinema transcends ethnic or national boundaries. A film lover is a resident of something we might call the World Republic of Cinema. Cinema has its own specific language and by becoming conversant in it, one should be able to understand the cinematic works of any filmmaker in the world. For someone who believes in the international nature of film, more than being Japanese, it is fundamentally important that Japanese cinema is cinema. From this perspective, lovers of Japanese cinema also love the films of John Ford, Godard, and Im Kwon-Taek.

Conversely, another viewpoint insists that Japanese cinema must be seen as part of the culture of Japan. After all, the camera movements of Mizoguchi Kenji are strongly influenced by the methods of traditional Japanese painting. Kurosawa Akira borrows many of the themes for his works from Kabukithe popular theater of Edo period Japan. Youth melodramas of the 1960s are sharply inscribed with the class divisions of postwar Japanese society, and to understand the anime of Miyazaki Hayao, one must know about the distinctive imaginative world of Japanese folklore. From this perspective, it is impossible to ignore cinemas intimate connections with Japanese culture, from literature to painting and theater. Or rather, you need to know not just culture but also the realities of Japanese history and society. Only when one can understand both the images in the hearts of the people who made Japanese films and those in the hearts of those who laughed or cried along when they watched those films is it possible to grasp the depth of Japanese cinema.

Which of these two perspectives is correct?

In fact, both are correct and both are necessary. Although Japanese cinema cannot be separated from the cultural particularities of Japan, we must also see it as a part of the universal history of humanitys desire for images and movement. The situation is the same in the United States. The depth of someones grasp of American cinema can vary considerably based on whether he or she is knowledgeable about the ethnic diversity of American society, or the New and Old Testament, or Jewish comedic traditions, or the trauma exerted by the Vietnam War. Yet, at the same time, it is precisely because film fans around the world have discovered something universal that transcends history in Japanese and American cinema that they love and respect them.

As a film historian, I would be delighted if Japanese cinema becomes a launching pad for the readers of this book to develop a general interest in Japanese people and Japanese culture. At the same time, I believe it would be equally wonderful if an encounter with Japanese films stimulates readers interest in seeing more films from around the world.