HAYAO MIYAZAKI

For Nurit, Matan, and Michael

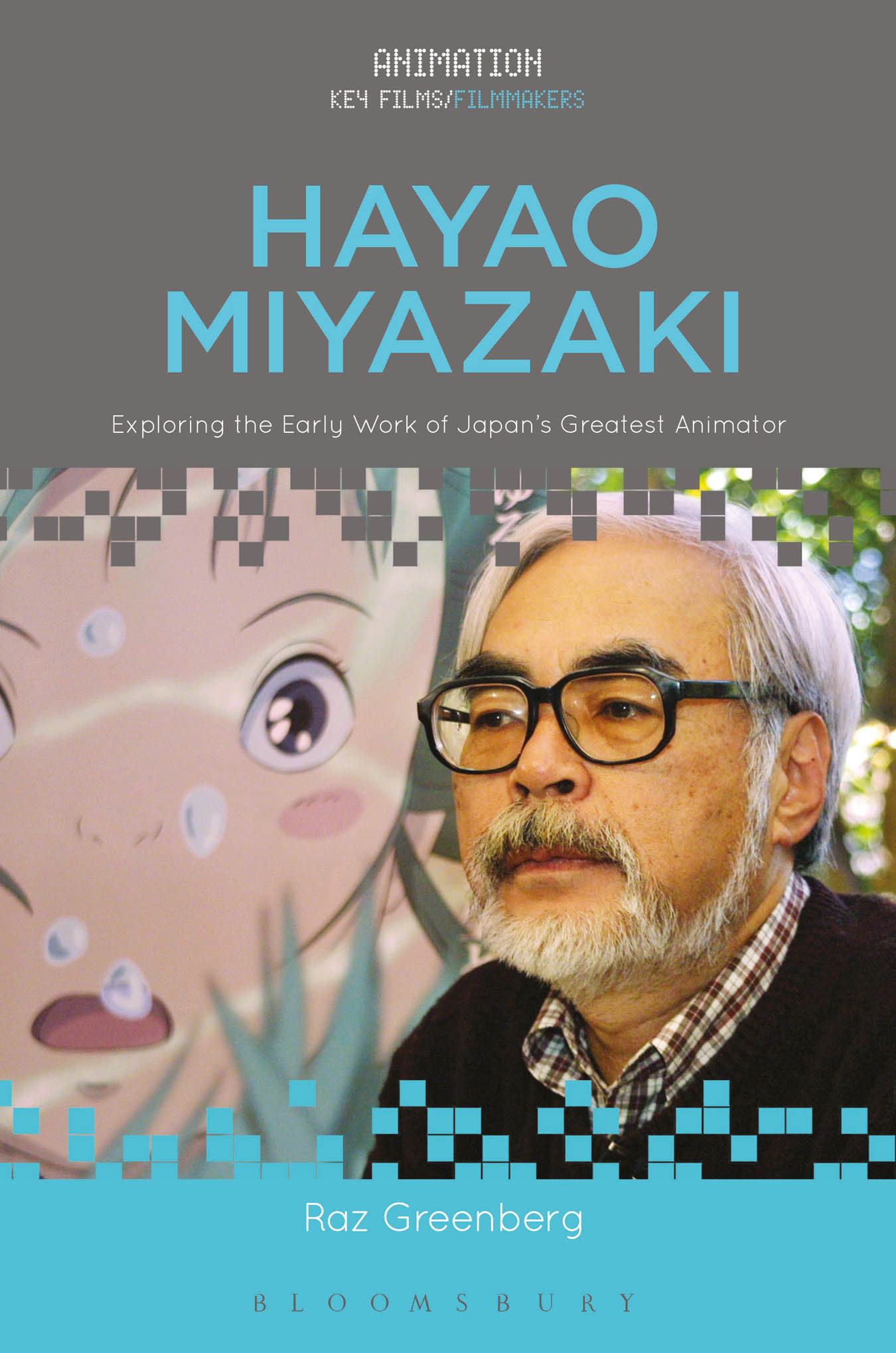

Animation: Key Films/Filmmakers

Series Editor: Chris Pallant

Titles in the Series:

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature edited by Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers

Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghiblis Monster Princess edited by Rayna Denison

Norman McLaren: Between the Frames by Nichola Dobson

C ONTENTS

This book grew out of the many projects that I have been involved with over the last decade, and I would like to thank the many people who supported my work on these projects. First among them are Professor Paul Frosh and Dr. Shunit Porat, who both supported, encouraged, and greatly aided my study and research into Miyazakis films and Japanese animation. Further thanks also go to Professor Esther Schelly-Newman for her support and to Professor Aner Preminger, whose seminar on intertextuality in the cinema provided me with useful tools and a chance to examine the connection between Miyazaki and the works that inspired him.

Following my study of Miyazaki, I have written about his work for both academic and popular publications. I would like to thank: Tsvika Oren, who edited a special issue on animation for the online journal of the Israeli art school Bezalel, for commissioning and editing an article by me about European motifs in Miyazakis works; Ben Simon and Randall Cyrenne of the Animated Views website, who ran an article by me celebrating 30 years of Miyazakis debut feature The Castle of Cagliostro; Rami Shalheveth, who published an article by me about Miyazakis film Castle in the Sky in the short-lived Israeli science fiction magazine Leprechaun; and Elsie Walker, who published my analysis of My Neighbor Totoro and its roots in childrens literature in the Literature Film Quarterly journal.

Special thanks also go to: Dr. Nissim Otmazgin, for some helpful bibliographical advice provided while working on this book; Jonathan Clements, for reading the books first draft and providing many helpful comments based on his extensive familiarity with the anime industry and its history (any mistakes are, of course, mine and mine alone), and to Mary Reisel for her help in obtaining bibliographical materials.

Another special thanks goes to the people at Bloomsbury Academic who believed in this book and made it possible: my editor Chris Pallant, Erin Duffy, Susan Krogulski, Katie Gallof, and Merv Honeywood.

Finally, I would like to thank my familymy wife Nurit and my children Matan and Michael, my parents, Yossi and Tzila, and my brother Shai, whose love and support made this book possible.

The initial inspiration for the writing of this book came from a childhood memoryone that I share with many other children of the 1980s in my home country (Israel). Throughout that decade, there was only a single broadcast channel available for us to watch, a public channel whose childrens broadcasting hours content was dictated by an educational agenda. In accordance with this agenda, many of those hours were filled with long-running animated shows that adapted classics of childrens literature, among them The Adventures of Peter Pan by James Barrie, Louisa May Alcotts Little Women, and many others.

One of the earliest of such adaptations to appear on the screen of Israels public channel, and definitely the most memorable, was Heart, based on the 1886 childrens novel Cuore by Italian author Edmondo De Amicis. De Amicis book followed the childhood of schoolchildren and the hardships they endure as their country becomes a modern nation-state. The animated show adapted and extended a short story from De Amicis book, about the courageous boy Marco and his journey from Italy to Argentina to find his missing mother. De Amicis novel had its share of fans among the previous generation of young Israelis who found the books patriotic spirit to be a good fit with their own countrys national mood in the 1950s and 1960s; by the time the show was broadcasted, many members of this generation had become parents themselves and they enjoyed rediscovering Marcos story alongside their own children, especially as it was given an excellent emotional Hebrew dub and its theme song was performed by one of the countrys most beloved singers. And yet, throughout the endless cycle of the shows reruns (almost every summer vacation), there was an element that left both the shows young and old viewers puzzled: why would a show about an Italian boy traveling to South America have Japanese-language credits at the end of each episode?

As subsequent animated shows that adapted classic childrens literature appeared on Israeli television screens, featuring a design style that was somewhat similar to that of Heart, their viewers became vaguely aware that these shows were produced in Japan; indeed, throughout the 1980s, it was the main exposure (alongside very few science-fiction shows) of my generation to Japanese animation. What we did not realize, at the time, was just how significant these shows werehow, despite adapting western literature, they very much reflected Japanese culture and, above all, the fact that the production of Heart employed the services of a man who at the time was already one of Japans most acclaimed animators, and who would go on to win an Academy Award in 2003 for his film Spirited Away: Hayao Miyazaki.

For me, this realization came toward the end of the previous millennium, when my interest in comics led me to the discovery of manga (Japanese comics) and anime (Japanese animation), further leading me to major in Japanese during my BA studies. It was during that time that I read and fell in love with Miyazakis manga masterpiece Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, shortly before being awed by his epic historical fantasy film Princess Mononoke (1997). I became a fan of Miyazakis works and, as I dug deeper into his filmography, I discovered that, along with his longtime partner Isao Takahata, he was indeed one of the people behind Heart or 3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother, as the show was known in Japan upon its broadcast in 1976. The design similarities between the show and Miyazakis later acclaimed works were strong, but as I watched and read more of these works, which led me to write my MA thesis about him, I understood that the connection goes deeper into the thematic foundations upon which Miyazaki rose to his prestigious position as Japans leading animator.

3,000 Leagues in Search of Mother is discussed in the second chapter of this book. Like the other chapters, it examines an important stage in Miyazakis early career, showing how it inspired his later acclaimed works. Although several books and many articles have been written about Miyazaki in English (an annotated bibliography of recommended sources is included at the end of this book), this book aims to be the first that offers deep examination of his early career in film and television, alongside works of film, television, and literature that inspired him, shaping his style and themes.

But there is more to Miyazakis early career than mere hints of his future acclaimed works. Anime scholar Helen McCarthy has described her wonderful book Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation (published in 1999) as a Miyazaki 101 introduction to the director and his works. This books aims at being Miyazaki in context in its reflection of how Miyazaki grew within the emerging post-World War II Japanese animation industry and how his rise within the same industry is a very important part of his country becoming an animation superpower, a status that it maintains to this very day. The two stories Miyazakis rise to prominence and the Japanese animation industrys rise to the same position are inseparable; each completes the other in showing the richness of styles, narratives, and themes that dominate both Miyazakis works and the industry as a whole, and this richness strongly echoes throughout the chapters that comprise this book.

Next page