THE ADVENTURES OF, THOMAS WILLIAMS, OF ST. IVES, CORNWALL,

PRISONER. OF WAR IN FRANCE, FROM MARCH, 1804 TO MAY, 1814.

I was taken prisoner of war by the French on the 28th day of March, 1804, during my apprenticeship on board the brig Friendship, of London (Josias Sincock, Master). We were coming from London to Devonport Dockyard, laden with copper and flour, and having weighed anchor in the Downs, after sailing down the Channel with a fair wind under convoy of the Spider gun brigthe Friendship not being a very fast sailerwe were detained to take on board a new long boat, which made us much astern of the fleet when night came on. About six o'clock in the evening I was on the forecastle looking out, when we espied a lugger coming towards the shore upon a wind, which went into land ahead of us, close under the stern of an East Indiaman, who was then reefing topsails. We lost sight of the lugger for some time, but at length espied her coming up close astern of us. We hailed her, but got no reply. Presently she sheared up under our quarter and hove a grapnel on board, followed by a great number of the crew who came on board well-armed and took possession of our ship, driving all the ship's company below, and keeping sentry over the hatchways. I was ordered on deck again to shew them where the leading ropes were. They soon altered our course for the coast of France, the lugger keeping us company the whole night. Early in the morning we came close into Dieppe, not having seen an English cruiser during the whole time. When the tide suited, we were put into the harbour, and the same night put into a round tower on shore, and kept there for three days. Before landing, however, they took away all our clothes except those we had on, and had the audacity to come to see us in the prison with some of our men's clothes on them, saying to us, Our day today; yours to-morrow. At the end of three days we were marched towards Givt and Claremont in the province of Ardennes, being the first day of April, 1804. I believe we were a fortnight in getting to our journey's end, being lodged in filthy prisons at night and marched with a guard by day having travelled nearly three hundred miles on a pound of brown bread and two pence-halfpenny per day, the latter being stopped when on the march. When we arrived at Givt prison we found several other ships' companies there before us that of H.M.S. Le Minerva, which was lost at Cherbourg; some of the Harwich Packet's, who were detained in the country at the breaking out of the war; some from H.M.S. Hussar, lost on the Saints' Rocks near Brest, with several others belonging to merchant men.

The prison in which we were confined was a very large horse barracks, divided into corridors or passages. Each corridor contained eight rooms, with accommodation in each room for sixteen persons. The doors were all locked at night. In the morning we were at liberty to go into a long narrow yard close to the River Meuse. This yard, when we were mustered (which was customary three times a day} would scarcely contain us. Our provisions from the French were very mean indeed: we had one pound of brown bread, half-a-pound of beef (said to be, consisting of heads, liver, lights, and other offals of the bullock, not very fat), a little salt, and about a noggin of peas, which were served to us every four days; and 3s. 4d. in money paid once a week. They would then deduct a certain portion from each person for the repairs of the prison, etc. We were so reduced, that we could scarcely fetch our own food from the town, which we were obliged to do every fourth day. The truth of this statement is emphasized in a book published by the Rev. R, Barbor Woolfe, the chaplain of the Dept, who came to the prison from Verdun some time after the Dept was established.

You can easily picture to yourself the state of society in such a place, without any restraint. Captain Jahlell Brenton, of H.M.S. Le Minerve, before he left our Dept for Verdun, laid down certain rules for the Commandant of the Dept to observe, with respect to the prisoners, as to spirits, beer, etc., which he strictly adhered to, as far as he could in a direct way; but the old men-of-wars men found out many inventions, and smuggling was carried on in every possible way, and you can easily guess what followed. In the meantime, however, amid much confusion, I did all I could to improve my learning, but not having many books, and wanting the means to buy paper, pens, and ink, my progress was not very rapid, but I did, with much pains and self-denial, get on pretty well with arithmetic. I then began to learn navigation, but having only one old bookHamilton Moore's Treatiseamongst us, I was obliged to copy out all the tables in that book before I could proceed with my learning. When this was completed I began study in good earnest, though very often, when I was in a corner with my books, the greater part of my room-mates were drunk and fighting all around me; but they never attempted to molest me. By close attention I made myself master of the science, and soon became a teacher to many others, thereby making myself more perfect, and receiving many a sol to help me in my own necessities.

Some three or four years after we arrived at Givt we were allowed one penny per day from the English, it was said to be from Lloyd's and, by this addition to our French allowance, although very small, we may safely attribute our escape from starvation.

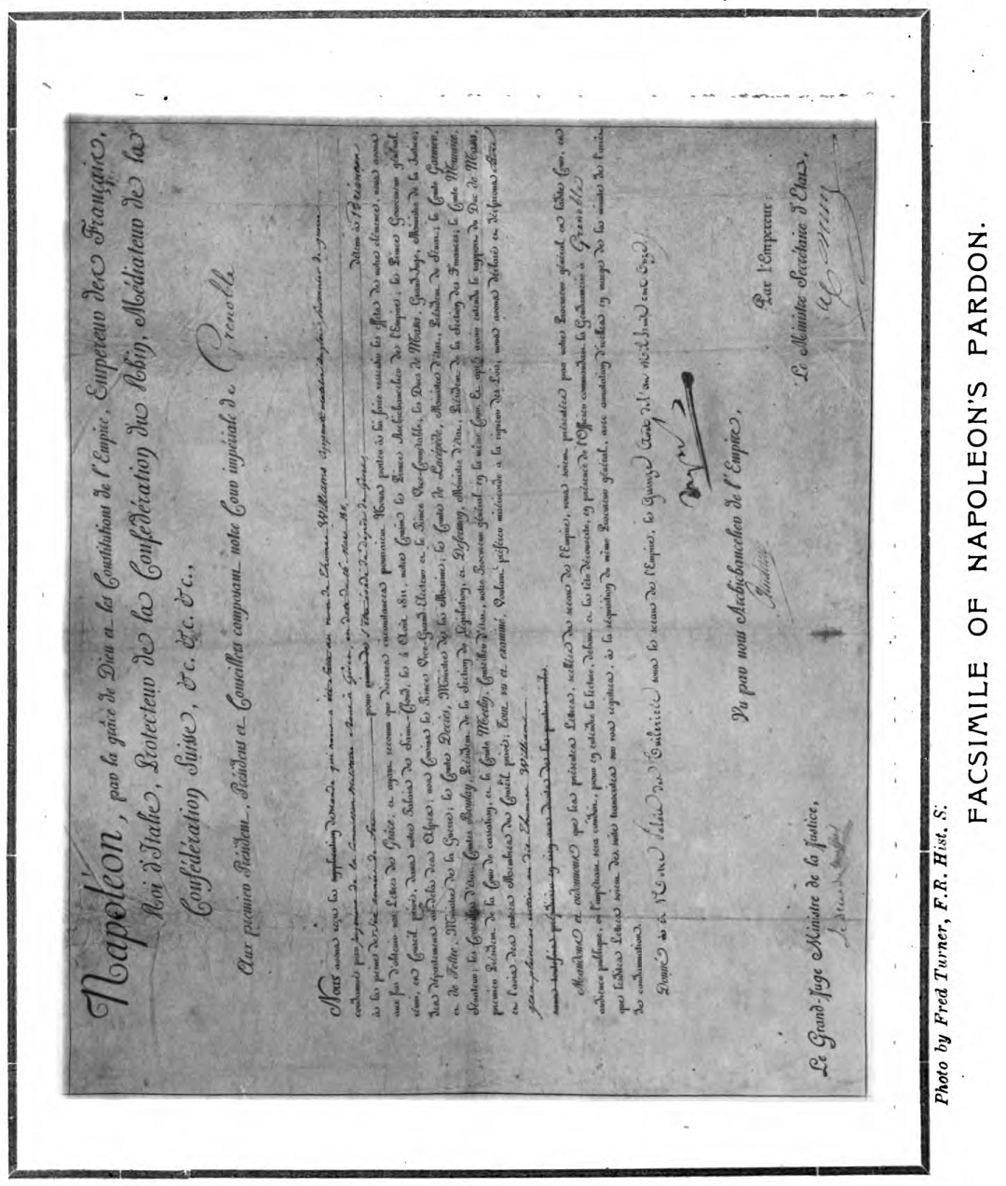

At the time of Mr. Wolfes coming to Givt, religion was at a very low ebb, almost everyone lived as they liked, not having many good books, or any place of worship. There were a few well-disposed persons amongst us, who endeavoured to do all they could to stop the tide of sin, but to very little purpose. Soon after his arrival he got permission from the Commandant to use a part of a granary over the prison as a place of worship; here we had service twice on Sundays and two or three times during the week. It had a very good effect on the Dept generally, and very many found pardon and lived consistently to their profession during the time I was with them.

Now after having been confined in Givt prison for about 7 years without hope of an exchange of prisoners, and having completed my lessons as far as permissible there, I made up my mind, with two others, to get away, if possible, and run all risk of life and limb, for they would not scruple to fire at you on the least alarm being given. Several of the prisoners made an attempt to escape, but being taken in the act, were cut and beaten most severely. Two midshipmen started from the town one evening and concealed themselves in a cave until night, but their own servant, a marine named Wilson, belonging to