THE LONG, LONG LIFE OF TREES

Copyright 2016 Fiona Stafford

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro and Copperplate by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016944967

ISBN 978-0-300-20733-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

C ONTENTS

B UDS , B ARK AND A G OLDEN B OUGH

T HERE is a pine cone on my desk, about the size of a sparrow. It is too fat for my fingers to encompass fully, but I like to feel the rough, woody flakes in the warmth of my palm. When submerged in water, each smoothly curved scale fits as tightly as tortoiseshell and then, as it dries out, the tapered cone quietly relaxes into a tough, dry ball. As the gaps widen, the unyielding chocolate-brown chips begin to reveal caramel-coloured chevrons, which mark their more contracted form. I picked it up on holiday in Croatia three years ago and so, as it opens, each wooden spatula offers a small scoop of unremembered time a sweltering trek through olive groves, an amphitheatre overlooking a busy harbour, a black octopus darting out from under a rock, creating drama in a quiet cove ringed by bright umbrellas and dark, stone pines.

Next to the cone is a little branch with a bunch of dried oak leaves, still firmly attached. There must be about forty, each one different in length, colour and curl. Their undersides are mostly like pale brown paper, lined with raised veins and marked with sporadic specks and flecks, but the topsides retain the deeper tan of polished, unstained leather. Their haphazard, waving, asymmetric outlines seem quietly anarchic. One reminds me of the last attempt at a pancake, when the batter is running out and no amount of tipping and turning will quite make a proper circle in the pan. The thin layers of crisped leaves harbour the smell of autumn and, if given a quick flick, will begin to mimic the scratching sound of the wind. The branch came from a mature oak a couple of miles from the house. I took it home when the land changed hands and the new owner began clearing old hedges and filling in ponds. Some of the acorns went into pots, some directly into odd corners of the garden to see if they would germinate. So far, the tree has been spared, but a few of its acorns have also sprouted into miniature versions with four or five small leaves of their own.

There are other things to plant. Black walnuts from a friends tree, which are sitting side by side like basking toads, some already dry and smooth, others much darker and slightly sticky; all giving off varied hollow tones when tapped. I have no idea whether any of them will ever grow into trees. Their smell is more pungent than that of the oak leaves, a more insistent reminder of the world outside. And there is a horse chestnut gathered one September from the stately grounds of Chatsworth House. It should have been planted years ago, but now that it has hardened and has lost all its gloss I leave it to take its place with the other stolen mementos and promises. It sits beside a sliver of birch bark, half unrolled like a small vellum scroll or an unfilled cigarette paper. The whole house is full of things that were once alive, from the bead necklace and the bamboo bookcase to the oak floorboards and the olive wood fruit bowl, the pine chest and the cedar pencil, the beech bread bin and the bentwood chairs. Somehow the little thefts from trees I have seen for myself provide quicker connections to the natural environment.

The oak branch is my golden bough, offering immediate safe conduct from one world to another. It transports me to a particular day and tree, and then on to other oaks and their places, some of these known personally, others vicariously through things I have been told, or through poems and stories, photographs and paintings. Sometimes it will take me full circle, from heroes to local histories, tales of magic and metamorphosis, panegyrics and protests, fables of planting and felling, and on through forests of wood carvings, masts, musical instruments and furniture, until I am back in the same room, surrounded by familiar things. They are never quite the same afterwards: the table is no longer just a table. Oaks, like every species of tree, bristle with layers of meaning, forever undulating, opening, growing, fading, interleaving. The golden bough takes me to imagined futures, too, which spring just as abundantly from the arrested buddings at the end of each dried-out twig. Most of all, though, it compels me outside, even on the coldest, wettest days, to breathe in life from the nearest trees and generally take stock.

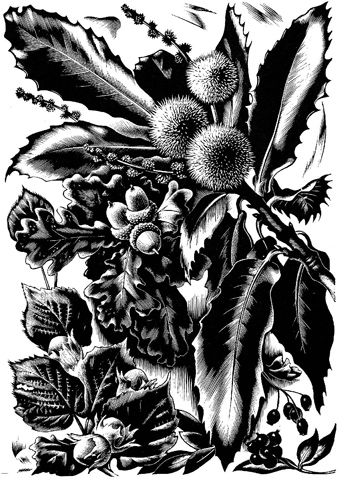

AGNES MILLER PARKER, ACORNS, BERRIES, CHESTNUTS, HAZELNUTS

Well, perhaps not on the wettest days. The local clay, cracked and hard in August, becomes so waterlogged in winter that field gates are almost impassable and the sensation of cold mud seeping over the top of a boot can detract a little from the beauties of nature. It is only after rain, though, that the trees become translucent, every extremity glistening with tiny crystal balls. A January morning can be the best time of all for seeing trees, because it is when the leaves have been stripped away entirely that the graceful symmetry of an alder or the wispy cascade of a silver birch is clearest. It is easier to spot things that are normally hidden away, too: last years nest of tangled sticks blotting the line of an upper branch, or an outcrop of creamy fungus, like a stand of ghostly parasols, at the foot of a nettle-free trunk. Even when the day is drenched in grey and there is hardly anything to be seen, the ashes will still be brandishing their black buds as if pointing towards some higher region of colour and light.

In spring, you can feel life stirring in the barest twigs and the silhouetted catkins look as if a diminutive duck has run across the sky. One day the twigs are just beginning to thicken and brighten and bulge; by the next they are covered in pincer-paired leaves and pale, lime-white or pink-tinged blossom. There is nothing tentative about these vernal explosions. When the days are longer, it is all sap and fresh smells, and the liquid calls of birds hidden in the drifts of thicker foliage. The bark has been through it all before, but the craggy faces of ageing willows and the peeling skins of cherry trees seem less pinched in the bright light. By early November, when it is all dank and dark, the woods have a different taste, which does not quite match the ember-fall, sugar-brown shaken leaves.

Next page