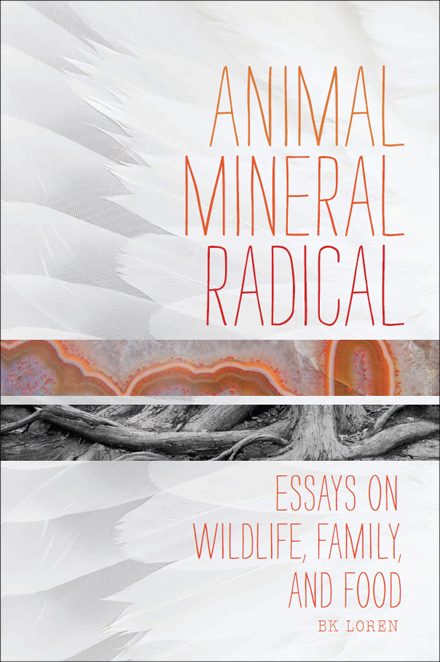

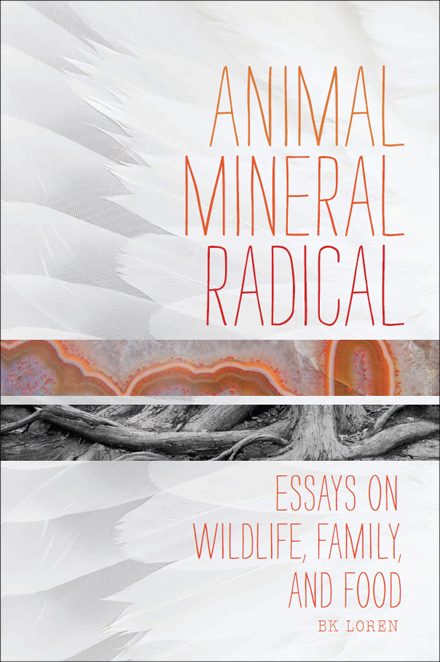

ANIMAL MINERAL RADICAL

ANIMAL

MINERAL

RADICAL

ESSAYS ON

WILDLIFE,

FAMILY,

AND FOOD

BK LOREN

Animal, Mineral, Radical:

Essays on Wildlife, Family, and Food

Copyright BK Loren 2013

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Loren, BK, 1957

Animal, mineral, radical : essays on wildlife, family, and

food / BK Loren.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61902-201-0 (ebook)

1. Contemplation. 2. Nature. 3. Conduct of life. I. Title.

BV5091.C7L668 2013

814'.6dc23

2012040570

Cover design by Domini Dragoon

Interior design by Tabitha Lahr

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Lisa Cech

always has been, always will be

AUTHORS NOTE

M ost names in these essays have been changed to respect the privacy of the individuals in the stories. Some of the places have been slightly changed if their exact location risks the privacy of the people involved. I strive for complete honesty on the page; however, I have no faith that recollection ever produces an absolute truth. Memory is never perfect, never static, and as far as I can tell, it evolves constantly with age. Im grateful for that.

CONTENTS

W riting is listening. I have never believed writing has anything to do with having something to say. It always comes to me as listening. Its a little like prayer, I imagine, though I have never leaned toward any religion. But Ive been told that, in prayer, there is a moment of asking for something, and then theres a longer period devoted to waiting. That waiting, in and of itself, decreases the desperation and the desire. In it, already, theres a giving up. It throws a person into a state of listening, andI would guessthe person who asked in the form of prayer begins to see and hear things that make sense in ways that hadnt before asking. In the aftermath, the ragged beauty and reason of everyday life become more lucid. This, to me, is the same process as writing.

If a person comes to writing with something to say, it risks drowning out this listening and replacing it with verbiage from the ego. I make no claims of lacking ego. But when I write, I pray that ugly beast retreats into its shell and lets something more important emerge.

Each essay in Animal, Mineral, Radical grew out of a great deal of silence and listening. At times, this silence-listening was forced on me by a physical illness that wracked my body for over a decade and, on occasion, took away my facility for language altogether. (I talk about this in Word Hoard, the final essay in this book.) During these years, I was unable to write a word. Then one day, on the almost-other side of the illness, I went for a short run. When I came back from the run I wrote the first three pages of Trends of Nature. I had never written creative nonfiction before, and I didnt know exactly what the lines Id written would becomea story? A poem? The form confused me, but I trusted it. I typed one page after the other, and then let the words stand on their own. I didnt worry about form or what I might do with the pages. I spent the next few months reading creative nonfiction, studying that form as I had others in the past.

More than ten years after I wrote Trends of Nature, Ive decided to gather a selection of these essays into a book. During this time, the writing world has changed about as much as my body and psyche changed during that long-term illness. When I first started to write again, the Internet was just on the verge of becoming the behemoth it is now. Facebook did not yet exist, CDNow was all the rage, no one had ever twittered a tweet, and a newish company called Amazon had yet to turn a profit. (Though it had been in business since 1994, Amazons first profit came in 2001.)

But these days the Internet is the center of all media and a focal point of many peoples lives. A few mornings ago, I awoke, bypassed the newspaper (as I have done for the past few years), and went straight to my computer for the news.

Though the essay didnt say anything I hadnt read before in some form, its concision and the overall cumulative effect of it and others like it sent me into a week or so of wrestling with what writing means today, what this book can possibly mean to readers. I looked back over the pages, and I remembered what it was like to write again after not being able to write for so long.

During that silent period, what saved me were my daily excursions into nature. I dont mean wilderness. I mean the small patches of nature available to almost everyone, no matter how mannered and procured the land may be. A tree in a planned park is still a tree, and sky will always be sky. Even these small remnants of the wild shifted my consciousness; I slowed down; I breathed differently; I listened, and the process was reminiscent of the days when I was able to write for hours. I felt a palpable connection between the mindfulness required by writing and the mindfulness induced by even the smallest bits of any natural landscape.

About this time I read a book entitled The Tree, by John Fowles, first published way back in the predigital age We jump to the end product and forget about the lengthy, multidecade process it takes to truly comprehend any art form. In short, he posits the notion that writingthe kind of writing that takes time and patienceis always in process and nature is always in process. Neither is ever finished. The flip side of this reveals that the degree to which we value writing that is short on process is on par with the degree to which we devalue the natural world. The care and patience that we are willingly forsaking in our approach to language, writing, and reading is directly related to the carelessness and lack of patience we demonstrate collectivelyand unconsciouslyto the natural world. If we lose patience and care in writing and reading, we will lose it in the way we view and interact with nature. Any aesthetic that devalues patience plows the cultural mind-field into fallow ground that begins to tacitly accept the inevitability of oil spills, deforestation, human-induced climate change (global warming), in short, into a consciousness that is linked to, if not synonymous with, the state of mind that allows commerce to take precedence over people and all forms of life.

And in the twenty-first century, it is far less literature that is in true danger than our attitude toward it.

I am keenly aware that, as a writer, I am not an anomaly. Most, if not all, working writers take care and patience with their words. But for every careful sentence that a writer labors over into the wee hours of the morning, there is also a professed cultural value for that which is quick, off-the-cuff, and uncrafted. If the editors of n+1 are right, and soon, if not yet already, it will seem pretentious, elitist, and old-fashioned to write anything, anywhere, with patience and care, then I hope Animal, Mineral, Radical offers a pretentious, elitist veritable fossil of a book.

But, smart and prodigious as their words may be, I thinkor maybe, I hopetheyll turn out to be wrong. No doubt we, as a species, have waged (are waging) war on the natural world. For the sake of our survival and that of other living beings, I hope we stop soon. But in the realm of geologic time, the natural world will continue; it will survive, with or without us.

Next page