Third Reader

by

Harriette Taylor Treadwell

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Row, Peterson and Company in 1912. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-267-7).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Purpose and Plan

Those who have examined this book, together with the Primer and First and Second Readers, should have no difficulty in apprehending the purpose of the series, to train children in reading and appreciating literature through reading literature.

The Primer contains nine of the best folk tales, true to the original, and yet written in such a simple style that children can begin reading the real story during the first week in school. The First Reader contains thirteen similar stories, of gradually increasing difficulty, and thirty-three of the best rhymes and jingles suitable for young children. This constitutes a course in literature, twenty-two stories and thirty-three child poems, as well adapted to first-grade children as are the selections for "college entrance requirements" to high-school students.

The Second Reader introduces fables and fairy stories and continues folk tales and simple poems. Others have used some of the same material in readers, but in a quite different way. Their purpose seems to have been to "mix thoroughly." We have organized the material: a group of fables, several groups of folk and fairy stories, a group of Mother Goose, of Rossetti, of Stevenson, and so on; so that the child may get a body, not a mere bit, of one kind of material before passing to another. Thus from the first he is trained to associate related literature and to organize what he reads.

The transition to this Third Reader will be found easy and to accord with the normal interests of the children. In prose the folk and fairy story is retained, but is merged into the wonder tale, which becomes a dominant note, while the fable gives place to more extended and more modern animal stories. The poetry begins with the group from Stevenson, whom the children have already learned to enjoy. Then follow selections from Lydia Maria Child, Lucy Larcom, Eugene Field, and a score of others dealing mainly with children's interests in animals and other forms of nature.

With these books, besides merely learning to read, the child has the joy of reading the best in the language , and he is forming his taste for all subsequent reading. This development of taste should be recognized and encouraged. From time to time the children should be asked to choose what they would like to re-read as a class, or individuals who read well aloud may be asked to select something already studied to read to the others. This kind of work gives the teacher opportunity to find out what is in a selection that the children like, and to commend what seems to her best.

The fact that some children voluntarily memorize a story or a poem should have hearty approval. It shows abiding interest and enjoyment, and it is likely to give, for the young child at least, the maximum of literary saturation.

The authors and publishers gratefully acknowledge permission of Charles Scribner's Sons to reprint the three selections from Eugene Field's "Poems of Childhood."

The Authors.

Contents

Group of Robert Louis Stevenson's Poems

Group of Lydia Maria Child's Poems

Group of Lucy Larcom's Poems

Group of Eugene Field's Poems

Group of Miscellaneous Poems

Group of Humorous Poems

Group of Miscellaneous Poems

The Enchanted Horse

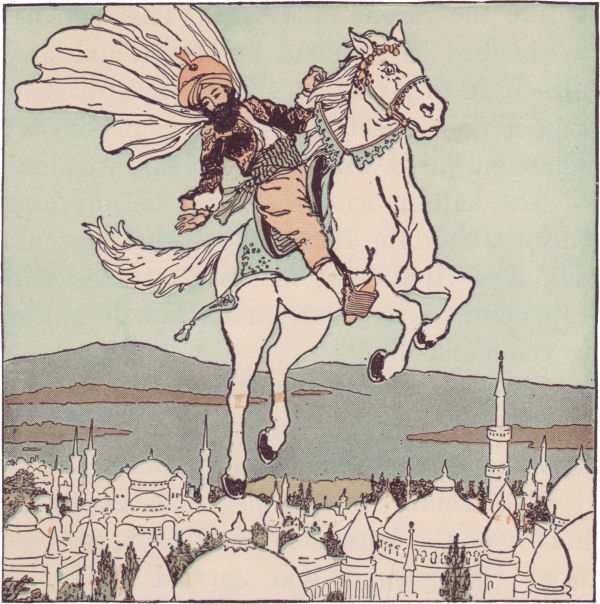

I N far away Persia the sultan held great feasts on the first day of the year. To one of these feasts came a Hindu with a wooden horse. It was so well made that it looked in every way like a real horse.

The Hindu threw himself upon his face before the throne, and said, "This horse is a wonder. If I mount my horse and wish myself in any part of the earth, in a short time I find myself there. If your majesty command me, I will show you this wonder."

The sultan, who was fond of anything curious, bade the Hindu show what he could do. The Hindu put his foot into the stirrup, mounted the horse, and asked the sultan to command him.

"Ride to yonder mountain," said the sultan, "and bring me a branch of the palm tree that grows at the foot of the hill."

The Hindu turned a peg that was in the hollow of the horse's neck. The horse rose from the ground and carried his rider through the air with the speed of the wind. In a few minutes the man returned with the palm branch and laid it at the feet of the sultan. The sultan was filled with wonder and wished to have the horse.

"Sire," said the Hindu, "I will not part with my horse unless I receive the hand of your fair daughter as my bride. This is the only bargain I can make with you."

The people laughed at this proposal, and the prince was very angry. "Father," he said, "I hope you will consider that an insult."

"Son," said the sultan, "I will not give him my daughter, but before I bargain with him try the horse yourself and tell me what you think of it."

The Hindu was delighted to have the prince try the horse. He ran before the prince to help him mount the horse, and to show him how to guide it. But the prince mounted the wonderful horse without waiting for the Hindu to help him. He turned the peg which he had seen the Hindu use. Instantly the horse rose into the air and they were soon out of sight.

The Hindu was alarmed. He threw himself at the feet of the sultan and cried, "Sire, your majesty saw that the horse flew away so rapidly I could not tell the prince the secret of bringing him back. Let us hope that he will find the peg which will do so."

The sultan saw the danger for his son. "May he not land on a rock or in the sea?" he asked the Hindu.

"No," replied the Hindu. "The horse will go where he wishes, and he will wish to land in a place of safety."

"Your head shall answer for my son's life if he does not return," said the sultan. He then ordered his officers to throw the Hindu into prison.

In the meantime the prince was carried into the air, higher and higher. At last he rose so high he could not see the earth. It was then he began to think about returning. He turned the peg the other way, but to his horror he found that the horse rose still higher. Then he remembered he had not waited to learn how to descend. He examined the horse's head and neck, and found a small peg behind his ear. He turned this peg and soon found that he was slowly descending.