Mauriac - 1972;1996;

Here you can read online Mauriac - 1972;1996; full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Paris, year: 1972;1996;2014, publisher: Flammarion, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

1972;1996;: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "1972;1996;" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

1972;1996; — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "1972;1996;" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

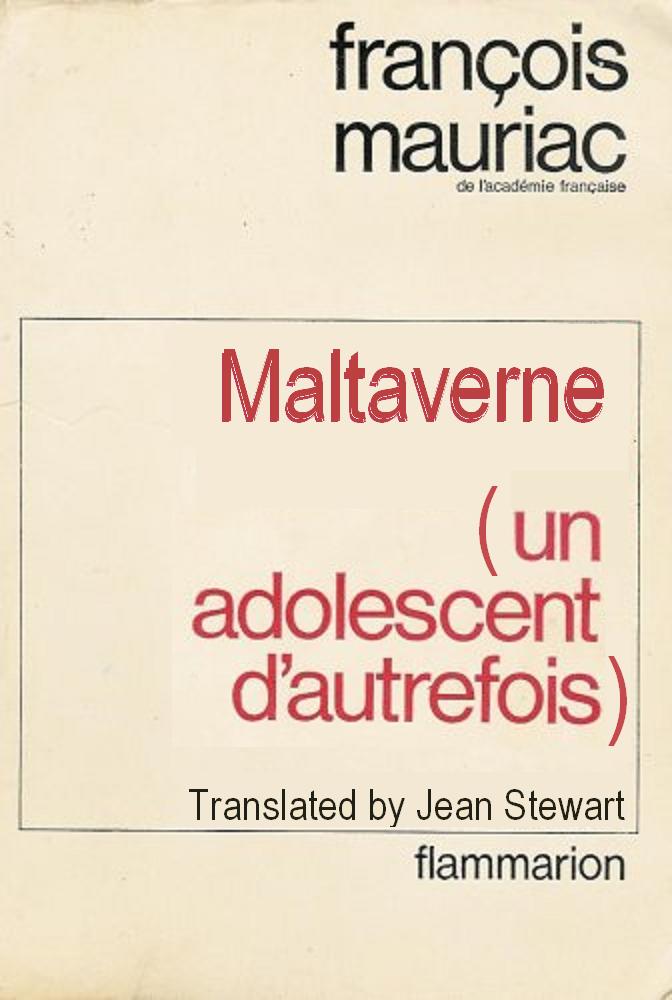

FRANOIS MAURIAC

Maltaverne

(Un adolescent dautrefois)

TRANSLATED BY JEAN STEWART

*

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published in French under the title Un adolescent dautrefois, Flammarion, 1969

This translation Maltaverne 1970 Eyre & Spottiswoode

All rights reserved

Library of Congress catalog card number: 70-113774

First printing, 1970 Printed in the United States of America

Table Of Contents

I write otherwise than I speak,

I speak otherwise than I think,

I think otherwise than I ought to think,

and so on into the deepest heart of darkness

KAFKA

I am unlike other boys. If I were like other boys, at seventeen I should go shooting with Laurent, my elder brother, and Duberc, our bailiff, and Simon Duberc his younger son, who is an abb and who at this time of day ought to be at vespers, and Prudent Duberc, his brother, who prompts Simon to make his bow to the cur. I should know how to use a twenty-four-calibre gun instead of beating the bushes and acting like a dog instead of pretending to be a dog.

Yes, Im pretending to be a dog, but at the same time Im wondering whats going on in Simons head. He has tucked up his soutane on account of the rushes and branches; why are his thick calves in their black woollen stockings so ridiculous? He loves hunting as the gun-dogs Diane and Stop love it; its in his blood, he cant help it, but he knows that at this time of day Monsieur le Doyen, who is serving Mass, is staring at the empty stall where Simon ought to be but is not. After vespers, M. le Doyen will come to our house to talk to Mother about it. I hope I shall be home by then, although they mistrust me and stop talking as soon as I come near. I talk a lot of nonsense, according to Mother, and M. le Doyen thinks Im perverse because I ask myself questions that he has never asked himself, that nobody, least of all myself, has ever asked him; but he knows that I think him stupid.

You think everybody stupid! Mother scolds me. At home, its quite true, no one seems intelligent except myself, but I know that I dont know anything because I have been taught nothing. My teachers had nothing to teach me beyond the rudiments of knowledge. My schoolfellows are better than I am at everything that matters to them. They despise me, and theyve every reason to despise me; I play no games, Im as weak as a chicken. I blush when they talk about girls and if they pass round photos I turn my head away. And yet some of them are friendly to me, even more than friendly.

They know what theyre going to do, they have jobs waiting for them. But as for me, I dont know what I am. Im well aware that the things M. le Doyen preaches and my mother believes bear no relation to reality. I know they have no sense of justice. I loathe the religion they practise. All the same I cannot do without God. Thats what makes me different, deep down, from all the rest, and not the fact that I play at being a dog and beat the bushes instead of shooting with Laurent and with Prudent and Simon Duberc, and that Im not even capable of using a twenty-four-calibre gun. Everything that M. le Doyen says seems to me idiotic, and so does the way he says it; and yet I believe its true, I might almost dare to assert I know its true, as if a blind man who was at the same time a professional guide might lead me to the real truth, by absurd paths, mumbling Latin and making others mumble it after him, though there are fewer and fewer of them and, in the end, a flock thats barely capable of grazing where he leads it. But then, they walk in the light without seeing it, while I see it, or rather its within me already. Let them say whatever they like: they are the dunces, the idiots that infuriate my friend Donzac, who is a modernist. All the same, what they believe is true. There you have the whole history of the Church, as I see it.

They got the hare on the edge of Jouanhauts field. The trek back was exhausting: seven kilometres along that gloomy road that Im so fond of, between two walls of pine trees: as far as you can see, it all belongs to Madame! Duberc invariably proclaims all along the road, with that extraordinary muzhiks pride of his Its horrible to be writing this. I knew beforehand that on the way back I should have Simon, the abb, walking beside me in silence. It was Laurent, now, who suddenly turned childish; he began kicking a pine-cone in front of him; if he got it all the way home hed have won.

Simon and I never talk about anything. He must have heard the cur complain of my perversity, and Simon admires me for being able, at seventeen, to disturb that narrow-minded man under whose thumb he will be so long as he is a seminarist on holiday.

Here I am going to admit, before God, that Im an impostor: if the Doyen is afraid of me, if Simon admires me, maybe, its on account of some vague notions Ive picked up from my friend Andr Donzac; hes always dinning into my ears what hes read in the Annales de philosophie chrtienne. Hes enthusiastic about a certain Pre Laberthonnire, an Oratorian who edits this review, and whose very name makes our Doyen see red: hes a modernist, he smells of the stake. I despise the cur for using that cruel, stupid image: the stake! Theyre ready to burn anyone who believes with his eyes open.

I am an impostor, none the less, since I bombard them with Andrs inflammatory comments as though they were my own, and pretend to know more than they do, although Im as abysmally ignorant as they are No, Im unfair to myself. As Andr says, I have got inside Pascal. I dont have to make an effort to read Pascal, particularly the notes in the Brunschvicg edition that Andr gave me. Everything that relates to Port-Royal moves me.

Simon Duberc has passed his bachot, but has he read Pascal? I suspect him of knowing none of his set books by direct contact, but only through the medium of his manual He was walking beside me. I was conscious of that smell of sweat in which his cassock is steeped. Not that he is dirty; he is cleaner than his peasant family, who dont know what washing means, and even perhaps than ourselves, since hes in the water almost every day, up at the mill pond where he goes fishing. He fishes for pike and dace by poking among the alder stumps, in front of which he has spread nets But I dont propose to tell fishing stories.

Really, its not so much Simons smell that makes me feel sick as that sixth little finger he has on each hand, that quivering appendage, and a sixth toe on each foot, so that his made-to-measure shoes look as broad as theyre long, like elephants feet! But I seldom have an opportunity to see those sixth toes, whereas that bit of boneless gristle on each hand fascinates me. He does not try to hide it, moreover, and rejoices openly that his extra fingers have enabled him to dodge military service. His elder brother Prudent thinks otherwise: You could have got into Saint-Cyr That was the only time I have heard Prudent play the tempter towards his younger brother, although thats the role attributed to him by Mother and M. le Doyen.

I have thought of a novel I could write round this theme: Prudent, who is lean, puny and swarthy, and whose teeth are all rotten, and who, I know, loves Marie Duros, the girl next door, the sister of Adolphe Duros who is twenty and looks like the picture of Hercules in my Greek history book Prudent might make use of his brother to be revenged on the world where he himself is a sort of mildew Except that, like all the Dubercs, he is intelligent. His revolt shows that. In the story I am inventing, Prudent would give up Marie Duros and bring her and Simon together. Actually Marie Duros must loathe the younger brother just as much as the elder and indeed much more, because of those little fingers and the way his cassock must stick to his skin What do I know about it? Ive made that up, but I am sure its true, because I know the boy that Marie loves, at least the boy she goes with, a friend of her brother, Adolphe the giant.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «1972;1996;»

Look at similar books to 1972;1996;. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book 1972;1996; and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.