A complaint: when a collective is necessary to bring something about.

Living in the Ruins

Introduction

Hannah M c Gregor, Julie Rak, Erin Wunker

A lot of sad feelings about CanLit. A lot of sad feelings about just fuckin being alive.

Katherena Vermette, Cant Lit

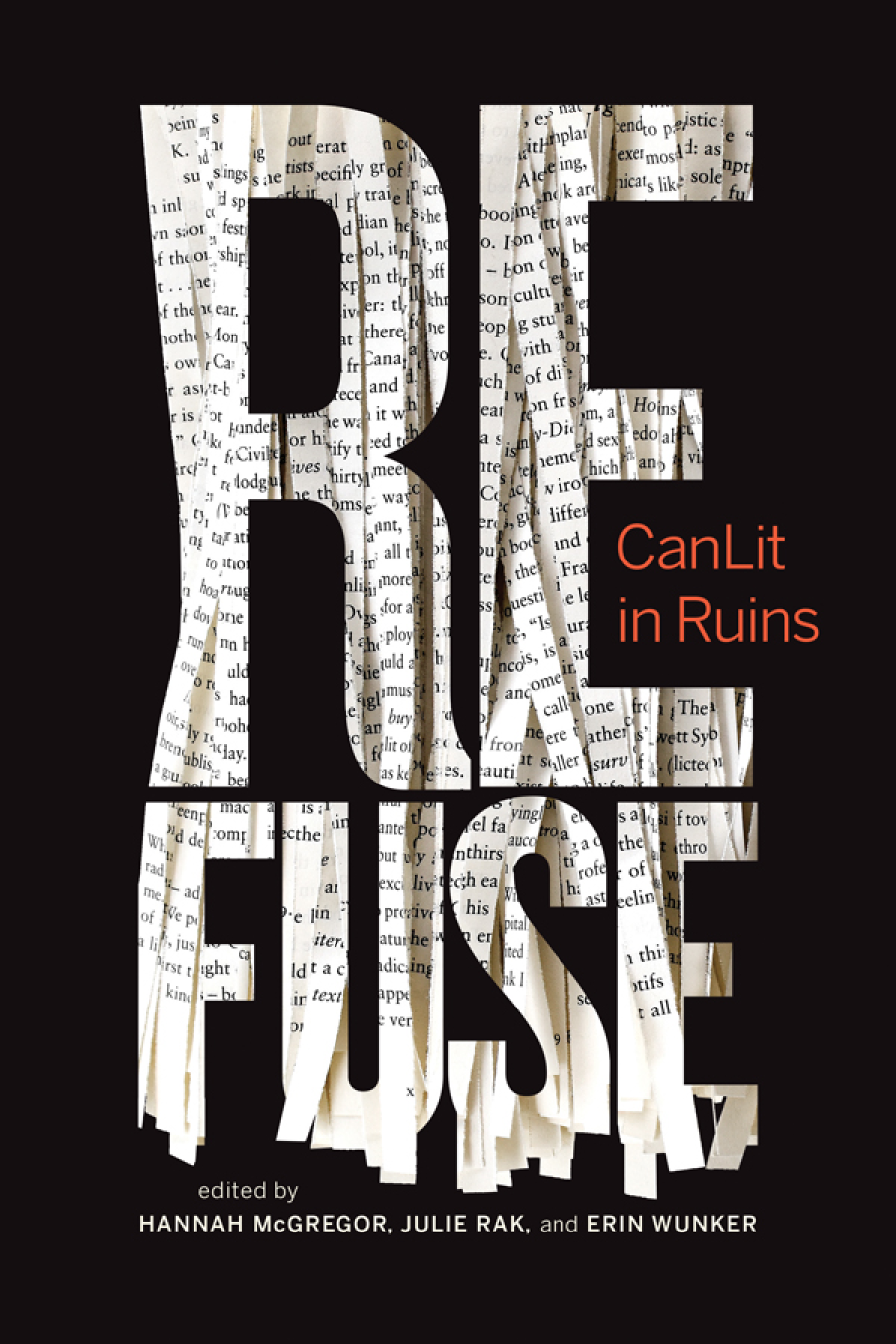

We think of refuse in many ways. It is saying no to the serious inequities, prejudices, and hierarchies that exist within Canadian literature as an industry (often shortened to CanLit) and an area of academic study. Refuse is another word for garbage, for waste. And what wastes our time, and our lives as writers and teachers, is the kind of endorsement of the status quo that we want to see taken out of CanLit. But refuse can also mean re/fuse, to put together what has been torn apart, evoking the idea that, after something is destroyed, something better can take its place. No matter what we mean by refuse, this much is clear: after a series of controversies and scandals, the signifier CanLit currently lies in ruins.

Somethings rotten in the (nation-)state of CanLit. And to point to that rot, we first have to do a few things. We have to name the symptoms, and we have to try to name the causes, including explaining what we mean by CanLit. We think the many writers generously lending their voices to this book can light a new way, and we wanted to make this book into a space where that conversation can continue to unfold, as it has already been unfolding, in poetry, journalism, tweets, open letters, and blog posts. Much of that conversation has been immediate and tied to specific controversies, and it is important that it not remain ephemeral within the debates about the state and future of Canadian literature. But the controversies themselves are also a symptom of deeper problems with CanLit and with Canada. Refuse works to connect urgent and immediate writing about this moment to long-standing problems in CanLit related to racism, colonialism, sexism, the literary star system, and economic privilege. That is our contribution to this important conversation about writing in Canada.

This isnt the last word on the subject. We hope that it is one contribution of many, and part of a larger conversation that seeks to understand the necessity of structural changes within many cultural industries and institutions.

Refuse as a contribution to debate has several goals. It is a venue for creative and academic writers to think about the recent CanLit controversies in light of the larger issues at stake. The collection also does the work of archiving and preserving important activist contributions that were part of the response to the controversies that have affected CanLit since 2016: notably UBCA ccountable, the sexual harassment revelations at Concordia University, the Appropriation Prize, and debates about Joseph Boydens identity claims. It is important not to lose that activist work, because many of the most significant interventions took place on social media or were written in ephemeral online venues. This introduction and the introductory material for each section aim to provide background about what has happened to CanLit, and to point out that problems with colonialism, racism, and sexism are not new to the writing, production, and study of Canadian literature. CanLit, to some extent, may even depend on the existence of such problems. Thats why we are thinking about CanLit as a formation in ruins. But we are most interested in thinking about how ruins might be figured not only as the ending of something, but also as the beginning of something else.

Living in the Ruins, Staying with the Trouble

In his important 1997 book The University in Ruins , Bill Readings says it is too late to save the institution of the university from its newest incarnation as a corporation, at the moment when its status as a symbol of the public good goes into decline. But, he adds, we can dwell in the ruins of the university and make something interesting happen, something that works against the university as a corporation but does not yearn for the old days, when universities supposedly mattered to the nation-state. In the ruins, the university will have to become one place, among others, where the attempt is made to think the social bond without recourse to a unifying idea, whether of culture or of the state. In other words, something new can come from something damaged. We think that CanLit, too, will have to imagine new connections that do not have recourse to a unifying idea of what Canada signifies, or even what it means to write in Canada, now. If CanLit as an institution is in ruins, maybe thats a good thing, even though it is a painful thing for many. These essays and poems point to some of the ways weve reached this place were calling the ruins, and they do so by thinking through or referencing many of the crises that have broken open CanLit. The contributors think about ways to stay in the ruins of a national literary culture that cannot and should not speak for all, and to learn about other ways of being and writing together.

The beginning of living in the ruins inevitably involves recognizing and then mourning what has been lost. As controversies about sexual harassment, neo-colonialism, racism, and industry hierarchies enter mainstream news cycles, it is increasingly impossible to believe that CanLit is an environment where diverse writing, and writers, can flourish. It is time to lose that pervasive, inclusive image of CanLit, because it is clear that CanLit is far from inclusive, or safe, for many of the writers working within it. If we dont own up to what CanLit is and what it does, we risk CanLit being an instance of what Lauren Berlant calls the state of cruel optimism, which happens when what we desire is an obstacle to our own flourishing. Cruel optimism is about a vague hope that things get better, without the political action needed to actually change what is wrong. Its about hanging on to ideals that will never come to be. If CanLit is a ruin we live within, we have to mourn the ideal of CanLit if we hope to move through it to something better than this.