Publication of this book was assisted by a grant

from the National Endowment for the Arts.

License edition and reproduction of microscripts

by permission of the owner of rights, the Carl

Seelig-Stiftung, Zurich Suhrkamp Verlag 1986

Translation 2005 by the Board of Regents of

the University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in

Publication Data

Walser, Robert, 18781956.

[Short stories. English. Selections.] Speaking to

the rose: writings, 1912-1932 / Robert Walser;

selected and translated by Christopher Middleton,

p. cm. ISBN 0-8032-4807-5 (cloth: alk.

paper) ISBN 0-8032-9833-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

I. Walser, Robert, 18781956Translations into

English. I. Middleton, Christopher, 1926

II. Title.

PT2647.A64A25 2005

833.912dc22

2005041793

PREFACE

The two earlier books of translations from Robert Walser, Selected Stories (1983) and Masquerade (1990), were drawn largely from Walsers eight collections of short prose texts published between 1904 and 1925. There were, however, in both earlier selections texts drawn from work not collected or published during Walsers lifetime. The present selection includes only two translations from his books. All else is drawn from that uncollected work, except for fourteen translations from what has come to be called the pencil area, or Bleistiftgebiet.

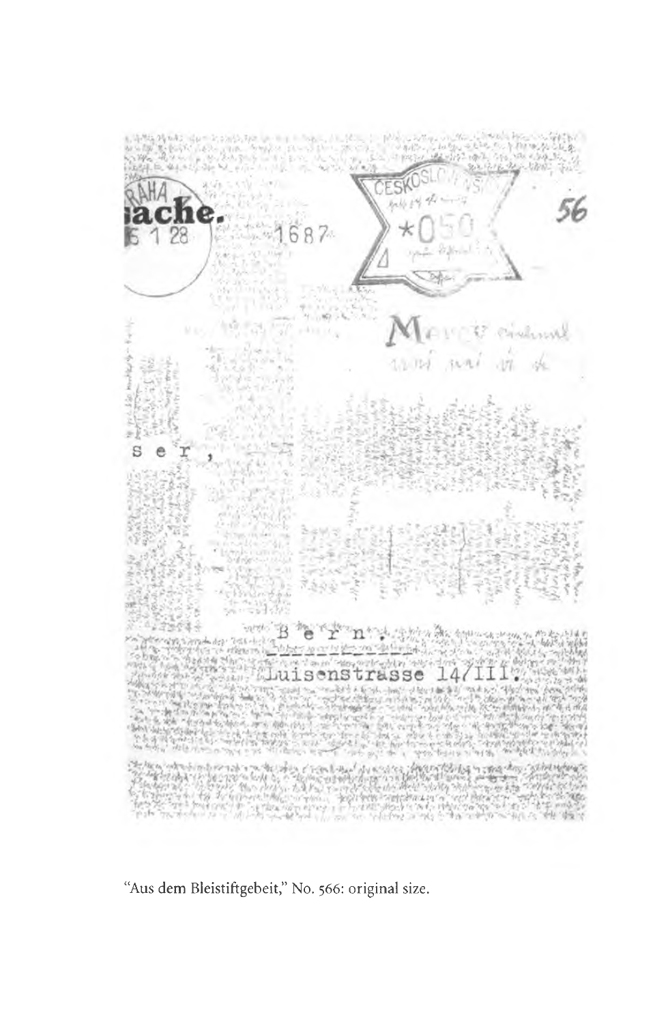

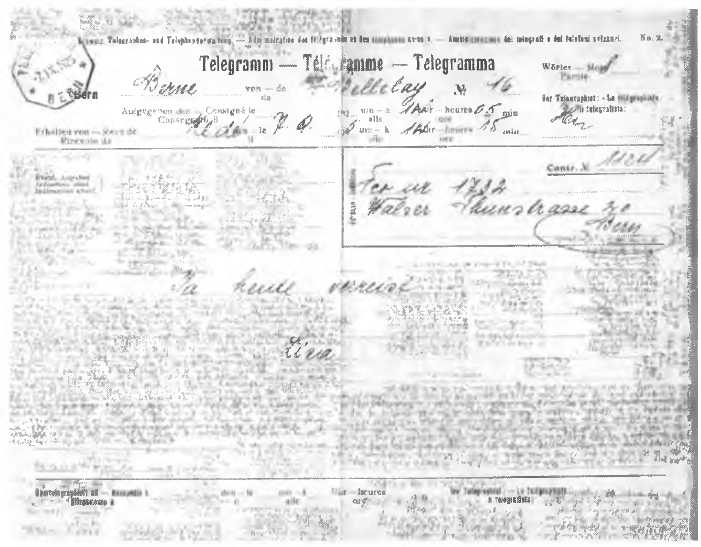

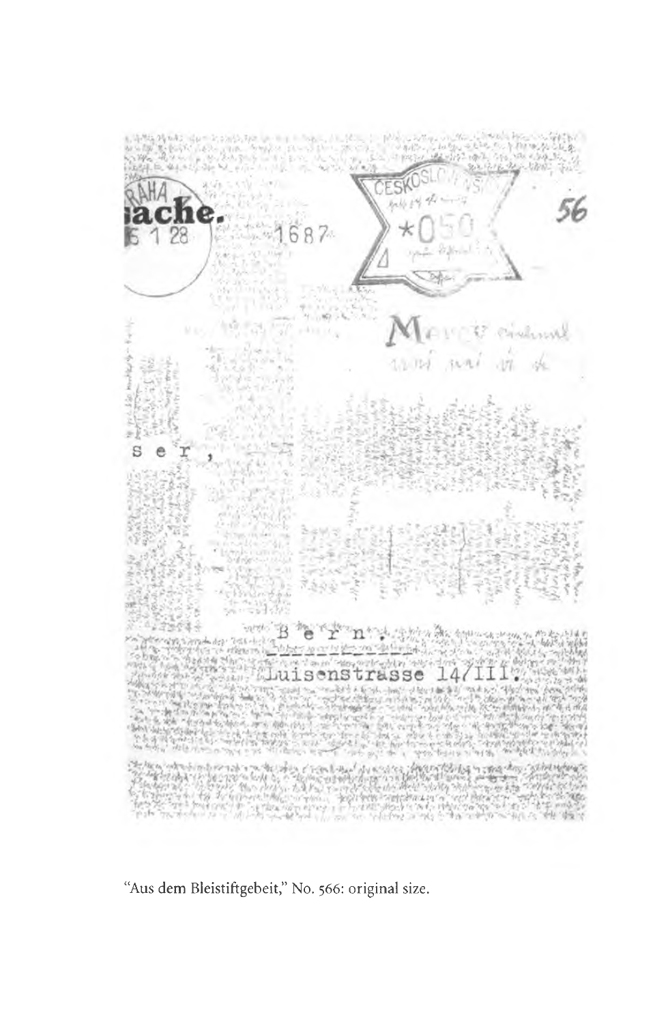

The pencil area was for a long time thought to be a corpus hermeticum, closed to the mortal mind because composed in an entirely private cipher. It was by matching certain strips of script to extant published texts that Jochen Greven first showed that the cipher had been all along an adroitly, if most idiosyncratically, abbreviated script. The 526 packages of this writing now fill 2,000 pages in the six volumes of Aus dem Bleistiftgebiet, 19852000, edited by the meticulous decipherers Bernard Echte and Werner Morlang. So here was a real trouvaille: sometime even before 1924 or 1925, Walser had begun to pencil, on the backs of calendars, on blank spaces offered by rejection slips, telegrams, bank statements, and other sorts of used stationery, an immense reserve of stories, feuilletons, sketches, improvisations, from which to extract, at will, fair copies. To make this new selection I then relied on volumes numbered 1520 in the collected works (Smtliche Werke in einzelnen Bnden, 1966), and on those faithfully deciphered multifarious calligraphic pencil microscripts.

The date at the end of each text is that of first publication or of writing: of the former when a source is spelled out, of the latter when followed by SW (for Smtliche Werke). Some notes, a chronology of Walsers life and work, and details of prior translations appear at the end of the book.

The chronological sequence of the texts should not be mistaken for a means to focus attention on Walser as a person. As author and individual, Walser articulates a large and general cast of mind, such as strictly personal writings seldom do. He can be considered a voice of the unvanquished downtrodden (in early work, of the employee), of people never quite small enough to slip through powers mesh, of the powerless who do not squirm but resist. Elusive as he is, his mimicries, his discontinuous digressions, ironies, even simulations, project an authentic and vital type, homo ludens , for whom creative play is the desirable thing, even the sublime thing. His prose, more agile than proper, more obstinately naif than burnished, certainly has ancestors, but it stands apart from other literary registers (as does that of Joyce or of Beckett). This otherness may be Swiss: that Walser spoke Swiss-German his prose does remind us. Yet he also did maintain a stand, seldom without his slingshot, in opposition to the grander writing in German of his time.

Through the 1960s, most of Walsers new admirers were apt to detect in his writings one single main (if secret) motif, such as Angst (Elias Canetti), Irony (Martin Walser), or else a type of folk tricksters Buffoonery. Spread the twenty volumes and the six of microscripts now before you, and such divinations are thrown in doubt. There are, for instance, several later straight texts about Jesus and his family, which cannot possibly be construed in the ironic voice audible in The Cave Man (We are workers, Christians). In the microscripts we can even discover Walser taking a positive shine to Catherine of Siena. No doubt his running contest with polymorphous selfhood finds a paradigm in worldwide religious exhortation to purge the soul of its deluded, layered, infernal self-will and unite it in charity with universal Spirit. Some of Walsers foibles might even have made him, in certain moods, a moderate Tolstoyan. But the selection I have made (not least for the pleasure of translation) does not in any way legitimize a religious, let alone Christian, reading of the entire work. To confine Walser, to locate his work, in any system of beliefs, or in any pathology (however generalized), can only be a most grudging response to the sensibility of such a wild particle.

The owl of Minerva flies, Hegel thought, at nightfall. Under Minervas tutelage Walser certainly was not. Yet there is an owlishness about his narrative gaze. While forging on with these new translations I have often been made aware of a daimon of owlishness exposing Walser at a curious angle to the European culture he had at his fingertips, while his spirited address to all existence had to meet, head-on, the catastrophic darkening of his times, their pivot being the First World War. Europe became a theme he flexes every which way, its chivalric past, the puny ceremonies of its present. And it is no small irony that such an enchanting disenchanter should write in 1927: In my opinion a writer who means to some extent well by his fellow beings should, if he can, so conduct himself as to help to save the illusions and protect them from being supplanted by illusionlessness.

The qualification to some extent surely touches with ambiguity the rest of the statement. To save the illusions: yet was the pencil areaas Werner Morlang has wryly suggesteda total work of art in a nutshell? The fourteen texts translated allow no more than glimpses of the whole fabric. And there it is, cryptically inscribed on ruins of paper, as if broken columns became trees again, and akin to Mons Desiderios seventeenth-century illusionary canvases of vast crumbling towers and palaces, a cosmos in fragmentation, the haunt (as William Gaunt wrote of Desiderio) of a lunar spirit which led to the construction of dead cities and disquieting arcades of fancy.

Even so, there is a caveat to be observed: the reader must bear it in mind that the B texts are the outcome of judicious and gradual deciphering, but not texts that Walser himself pruned, polished, and proofread. We must devoutly allow for a difference in kind, and as regards internal consistency, between microscript and finished work. The translations pass over only a few and not substantial doubts as to the transcription (such as are editorially indicated in the source).

Next page