This story, like another, begins with an apple. The apple in my tale was not ripe and tempting but wrinkled and old, too high to pluck and too stubborn to drop. It hung from a whip-thin branch, dancing in the cold March wind. The goats pranced around the tree trunk, bleating their frustration.

Do not be so greedy, goats, I called as I climbed. You are so much like pigs that Cook will carve you into hams! But I laughed as I scolded to lighten the threat. The branches clawed this way and that, for the orchard had not been pruned in two years, and the shoots were as tangled as bird nests. Stop scratching me, tree, I whispered. I will not hurt you. I promise. The apple tree was higher than I had supposed, but I am not feared of heights and I am not feared of climbingyoucould climb a cloud, Father Petrus used to say, may God rest his soul. Youre a miracle, Boy, he would add, so often that I almost believed him.

Up I climbed, till my head was as high as the orchard. I could see the manor, guarding us from wicked men. Goats, I called, I can see our shed!

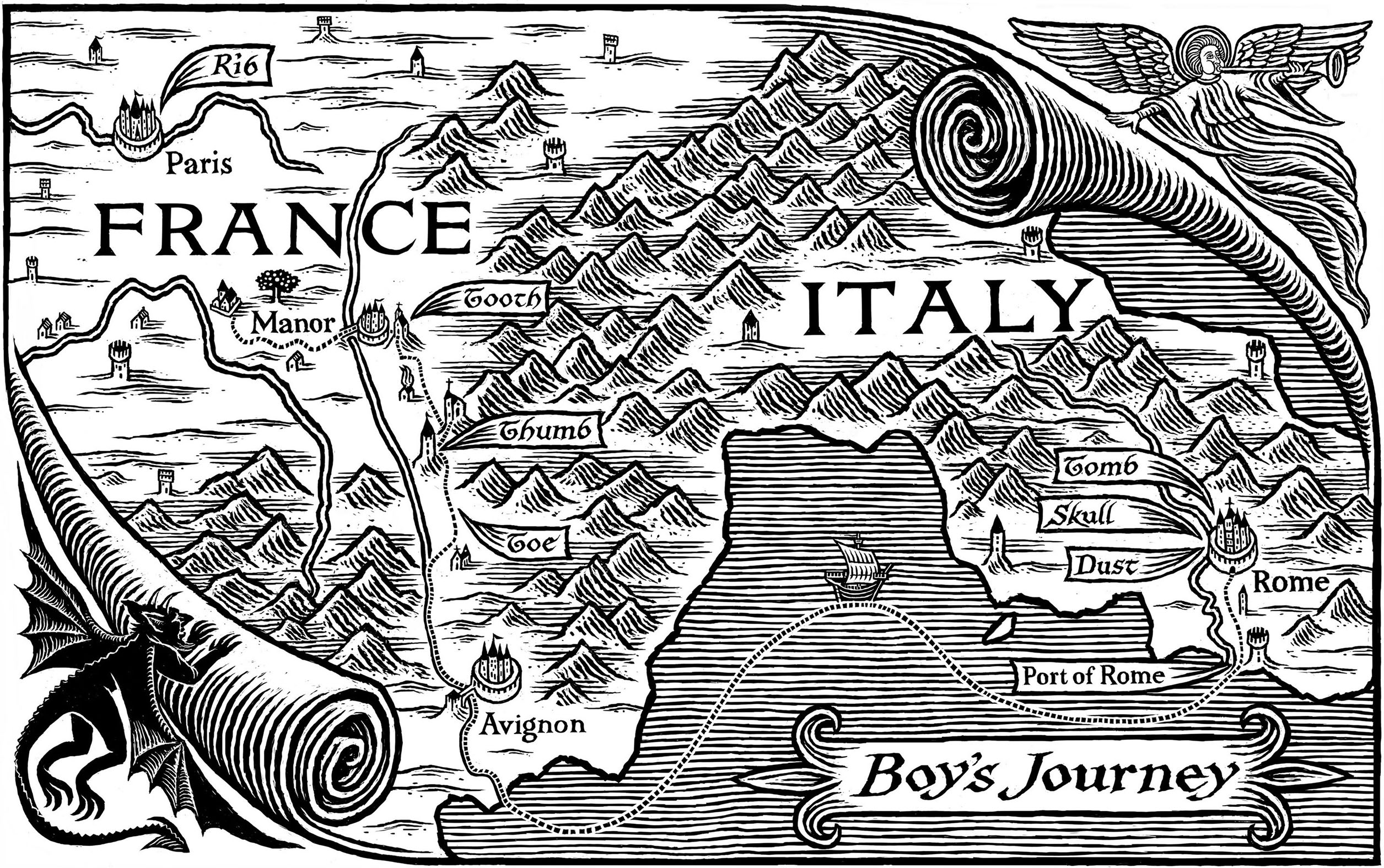

Twas then I glimpsed the pilgrim. The goats could not see him because the ditches also had run wild these past two years. He is tall, goats, and wears a brown pilgrim robe and cloak and wide hat, with a staff as tall as he, and he carries a pack on a long pole. Perhaps he journeys to the Holy Land, or to Rome to see the key to heaven. I marveled at a soul so fortunate as to travel the earth whilst seeking Gods favor, and I waved. But the pilgrim did not wave back.

So I resolved to impress him. I walked along one branch and another without even holding a twig, for pride is the downfall of every soul. Closer I stepped to that apple... I leaped and snatched it, and I fell through the chill March air, but I am not feared of falling, and I tumbled on the cold ground with leaves on my hood and a laugh on my lips. Naught in the world is so joyous as the feeling of flight.

The goats pushed in: bah! they snorted. You should jump less and feed us more. The brown nanny snatched the apple from my fist and dashed off, her eyes gleaming with gluttony, for goats know well the vices.

I lay giggling at life and the goats and the bright cold day. Twould not be cold forever, and soon enough the apple blossoms would swell as life swelled already in the bellies of the goats....

The pilgrim loomed over me, the brim of his hat blocking the sky.

Oh, he startled me. This was my orchard, a place for me and the goats.

Whos your master? The pilgrims face was shadowed, his voice dark.

He did not even greet me. Should I greet him? Was it my place to?

Do you speak?

Y-yes.

Where would your master be?

I scrambled to my feet, brushing dead grass off my hood and goatskin and hose. The pilgrim had a dozen pilgrim badges pinned to his hat: the shell of Saint James, the head of Saint Thomas... goodness but this man had traveled far.

I pointed across the weed-choked ditch toward the manor. There.

Hmph. He turned, staff in hand, and started off. Well? Take me there.

Oh! Yes... milord. I should add milord, to be polite.

And stand up straight.

My cheeks flushed. Why did he notice? Why did everyone notice? I am, I whispered.

Hmph. A hunchback. You can walk at least. He snapped his fingers at the pack he had been carrying, the pack on the end of the pole. Bring that for me. And careful: tis worth more than you are.

I hurried for the pack, unsure whether to hold it in my armswas it truly worth more than me?or to balance the pole on my shoulder as the pilgrim had. The goats gathered around, but I held the pack out of reach. No telling what a goat might do.

I set off after the pilgrim, keeping my head down. Everyones a hunchback when they hunch.

He strode toward the manor, not asking the route, but he did not need to, for the goats had marked the path in their way. I followed, the pole tangling in my legs. He moved so fast I had to trot.

What do they call you?

I sensed him staring at me, and wished he wouldnt. Boy.

He snorted. What does your mother call you?

Havent got a mother.

Ah. Pestilence.

Never had one.

Never? he asked mockingly.

I shook my head. Father Petrus hadnt been a mother, though hed come close. He was the one who named me Boy. Never reveal yourself, Boy.... He hit me when he spoke this, to make certain I minded.

What of your father?

I shrugged. The manor had more than one child without a pa.

Beneath the wide brim of his hat, his eyes caught the light. Ah. The face of an angel and body of a fiendI suppose that defines a boy right enough.

Not a boy. Boy. Thats my name. I did not care for the words he tossed about. I did not care for people calling me anything other than Boy.

We passed the huts, or what was left of them. The pilgrim walked straight, not following the swerve in the trail, for even the goats avoided the huts.

In the first hutnow a blackened scar full of two years weeds had lived a shepherd, God rest his soul, who played a pipe. He had promised to teach me, but pestilence took him away before he could. Perhaps he lived now in paradise, piping.

The second hut once held a widow and her son. They perished, too, the both of them. They went to sleep but never did they awaken, and their hut was now only four charred posts. Please, I prayed. Heavenly saints, see them into paradise.

I crept past the final hut, its thatch rotting and doorway dark. No one had been left to burn it. In that place lived the family that called me a monster, even the smallest who barely could talk, and the mother laughed when her children threw stones.

I tried to pray for them as I passed, but the words would not form in my mind. My fingers reached beneath my hood for the scar on my scalp. May God forgive my absence of mercy.

Both hands with that pack, Boy, the pilgrim ordered, his boots crunching on the frosty grass.

Quick I snatched my hand back. I did not like this pilgrim. I did not like a man who saw what he neednt and did not fear what he should. This pilgrim man was dangerous.

The pilgrim broke a path through the ditch. I hurried after him, the goats close behind me, for the ditch had been known to shelter wolves.

There stood the manor on its hill, vineyards draped around it like a fine ladys skirts. Sir Jacques is there. I pointed. Milord.

Take me to him.

But What to say? I swallowed. Yes, milord.

The goats held back as we climbed the hill. We were none of us welcome at the manorI because of my hump, and the goats because they irked the dogs. We had been welcome once, for milady enjoyed the goats spunk and my service, but milady was gone now, milady and her three sweet babies, and another woman made the rules.

The dogs ran up when I entered the courtyard; we were great friends, the dogs and I. They kept their distance from the pilgrim, however, for dogs are wise to strangers. I hunched inside the wagging circle, holding the pilgrims pack away from their curious noses. Keeping an eye out for stones.

To Jill

To Jill