I have yet to see any problem, however complicated, which when you looked at in the right way did not become still more complicated.

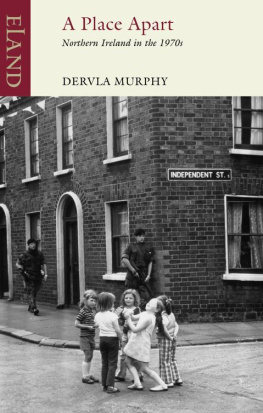

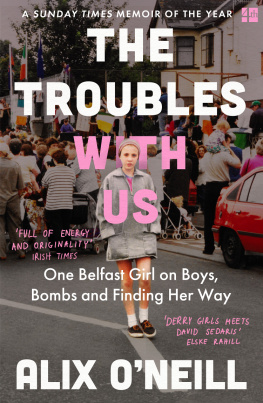

Before June 1976 I had spent in Northern Ireland precisely thirty-six hours out of forty-four years. My one crossing of the border, in September 1973, was to give a talk in Enniskillen; and as soon as possible I was on my way home having felt no urge to stand and stare. To me, in County Waterford, Northern Ireland was merely a squalid little briar-patch swarming with human anachronisms who often seemed sub-human and seething with dreary dissensions punctuated by ghastly excesses. Since there seemed to be nothing anybody could do about it, it was best forgotten. So I went to South India that winter, and to Baltistan the following winter, and wherever I went people asked me why Christians were fighting in Ireland. To which I replied impatiently that I didnt know myself. It never occurred to me that this reply, from an Irishwoman, betrayed an attitude both stupid and unkind; even, some might say, irresponsible.

In the spring of 1976, after listening to two of the more bone-headed Northern politicians arguing on the wireless one evening, I was appalled to hear myself saying viciously, Why dont the Brits get out and let them all slaughter each other if thats how they feel? Theres nothing to choose between them. Why did we ever long for a united Ireland? It was then that this book was conceived, by shame out of repentance. It is not a study of history, politics, theology, geography, sociology, economics or guerrilla warfare. It is simply an honest portrayal of emotions my own and other peoples and an attempt to find the sources of those emotions. At one stage I had hoped to be able to clarify the present Northern Irish turmoil for the ordinary citizens of Britain and the Republic. But the more time I spent up North the less capable I felt of doing any such thing.

In Ireland, during recent years, many Southerners have been voicing anti-Northern sentiments with increasing vehemence and frequency. Some such outbursts may be excused on the grounds of frustration and despair but most, I fear, are symptoms of a spreading infection. To me it seems unlikely that the Norths physical violence will ever overflow seriously into the South, yet this is a tiny island and gradually the emotional violence up there has affected the atmosphere down here. Moreover, because the Provisional IRA hope one day to be free to transfer their attentions to the Republic, many less optimistic than myself feel threatened by the Northern chaos. And the maggots of bigotry breed so fast on fear that we may soon see a new form of intolerance in Ireland, between Southern and Northern Catholics.

It is ironical (or do I mean comical?) that so many in the Republic are so thankful now that Westminster rather than Dublin is responsible for Northern Ireland. And it seems odd that, despite decades of political bombast and emotional white-heats about a united Ireland, so few of us have ever crossed the border or taken a normal neighbourly interest in our Northern fellow-countrymen. It is true, sadly, that there is nothing tangible we in the South can do. But the intangible also counts. Why should we not travel in the North to express a concerned interest in the people there and to see for ourselves what really goes on, as distinct from what the media choose to tell us? When I urge my friends to holiday in Northern Ireland they look at me as though I were delirious. Yet it is an entirely sensible suggestion, from every point of view. Visitors from the South would find books, beer and butter cheaper than at home. And they would find the people as welcoming, the scenery as good, the roads better and the weather no worse.

Having cycled hundreds of miles through superb countryside, and into (and safely out of) dozens of small towns and villages, I feel no hesitation about recommending the rural North of Ireland as a holiday area for families of any nationality. During July and August I was accompanied by my seven-year-old daughter, Rachel, who rode her pony, Scamp, for more than 300 miles while I cycled ahead and her elkhound, Olaf, trotted along behind. We camped out in a tiny tent in the counties of Fermanagh, Tyrone, Londonderry and Donegal and spent one night in a field bisected by the border. While we slept in Northern Ireland Scamp grazed in the Republic. It was not a bit like what you read in the papers.

However, these were not my sentiments as I cycled North in early June from my tranquil home in the far South. I then experienced, at intervals, sick little spasms of fear. Even those of us who cherish our independence of thought can no longer protect our emotions from the influence of the media; though we may continue to think for ourselves, our feelings are all the time being manipulated. Also, for weeks my local friends (perfectly sensible people, most of them) had been begging me to forget Ulster which naturally increased both my determination to go and my nervousness. Never before had I embarked on a journey that required courage.

The difficulties involved in writing about Northern Ireland at this time will be apparent to every reader. In a situation that has developed out of centuries of fear, distrust, resentment and contempt, the enquiring outsider is given an enormous amount of biased misinformation. I discarded as likely to be inaccurate at least 75 per cent of the facts I collected. But this does not mean that my collection was worthless; the manner in which facts are consciously or unconsciously distorted, and the reasons why they are distorted, can be very illuminating.