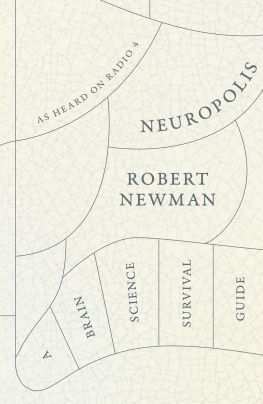

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Text Robert Newman 2017

Cover design by Jonathan Pelham

The author asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008228651

Ebook Edition April 2017 ISBN: 9780008228699

Version: 2017-04-11

For Yana and Billy

LIST OF CONTENTS

To read the current crop of brain science books and articles is to discover that we live in a colourless, odourless, tasteless, silent world,

David Eagleman, The Brain: The Story of You , 2015.

V. S. Ramachandran, Phantoms in the Brain , 1998.

Dick Swaab, We Are Our Brains , 2014.

Brian Cox, interview by Hannah Devlin, The Times , 6 September 2014.

David Eagleman, The Brain: The Story of You , 2015.

This sort of talk slanders and libels us but it is also very funny with its runaway extrapolations that leave science far behind. In fact this book grew out of a stand-up comedy show called The Brain Show , which toured for a hundred gigs, and then developed into a BBC Radio 4 comedy series.

My argument in this book is that brainless interpretations of brain science are doing our heads in more than we know by giving us a dehumanising and pessimistic picture of ourselves. This picture, I argue, derives not from science at all but from philosophical stowaways. Indeed if we look at what the latest neuroscience actually tells us, then a very different picture emerges.

But who are you to talk about any of this? was one interviewers opening question to me on live national radio. I opened and closed my mouth like a roach on a riverbank. Minutes passed. I just didnt know what to say. I never did come up with a reply. Who am I indeed to trespass on the brain scientists bailiwick?

In his 1940 lecture series Dynamics of Psychology , however, German psychologist Wolfgang Khler praised trespassing as a scientific technique, on the grounds that what is merely special data in one field may turn out to have much broader significance in another. Now this doesnt mean the trespasser sees the big picture in a way that eludes everyone else. Trespassing can be helpful by accidentally treading spores from one field into another, where they unexpectedly start fizzing and wriggling into life. Or the trespasser might find fertilizer sacks full of rubble and rusty cogs blocking the entrances to badger setts. Certainly one of the great joys of researching this book has been to disinter fascinating brain science buried under all the reductive bluster.

And then theres the fact that brain science appears to have arrogated to itself all understanding of human behaviour anyway, which makes it kind of hard to move a muscle without trespassing. In fact, since the brain science fiefdom now includes life, the universe and everything, the question is who is the real trespasser here? In the words of the great comedian Michael Redmond:

People are always saying to me, What are you doing in my back garden? To which I reply: What are you doing in my house?

Lets go and climb the back steps and see what they are doing in our house.

From the get-go, it is important to remind ourselves that brain-imaging does not actually film your brain in action. There is no live action footage of thoughts or feelings. No one will ever be able to read your mind except your mum. Brains do not light up during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG). Strictly speaking fMRI and EEG are not techniques of brain imaging but of blood imaging, since they track blood flows to different brain regions on the working hypothesis that active neurons devour more oxygen, and blood is the brains oxygen delivery service.

On 17 May 2016 the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA published the first comprehensive review of 25 years of fMRI data. The conclusions were damning:

Anders Eklund, Thomas E. Nichols & Hans Knutsson, Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates , PNAS , 2016.

In theory, we should find 5 per cent false positives but instead we found that the most common software packages for fMRI analysis can result in false-positive rates of up to 70 per cent. These results question the validity of some 40,000 fMRI studies and may have a large impact on the interpretation of neuroimaging results.

In 2009, the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science published Puzzlingly High Correlations in fMRI Studies of Emotion, Personality and Social Cognition. (Original title: Voodoo Correlations in Social Neuroscience). Two of the papers authors, Ed Vul and Harold Pashler first became suspicious when they heard a conference speaker claim he could predict from brain-images how quickly someone would walk out of a room two hours later. This had to be voodoo.

Ed Vul et al ., Perspectives on Psychological Science , 2009.

Imagine a scenario in which roaring floodwaters smash the office windows. Your colleagues flee, but then turn back to see you stranded in the rising water.

Save yourself! they cry. Run for you life!

You go on ahead, you holler back. Im not gonna make it. I decided a couple of hours back on an airy saunter through the doorway.

Well, sashay for your life! Mince like youve never minced before!

Vul et al. set about re-examining the data. They surveyed the authors of 55 published fMRI papers and found that half acknowledged using a strategy that cherry-picked only those voxels exceeding chosen thresholds. These cherry-picked voxels were then averaged out as if they were the average of all voxels, not just the ones that fit the hypothesis they were supposed to prove. This strategy, says Ed Vul, inflates correlations while yielding reassuring-looking scattergrams.

Voxels are the organisation of statistical correlations into cuboid 3D pixels. Each cube represents a selective sample of billions of brain cells. They provide a computer-generated image of what brain activity would look like if cherry-picked statistics matched raw data. Together the cubes build a Minecraft map of the mind.

To form each cuboid voxel, you collate all the neuronal clusters that have a blood oxygen level of x at split second 0.0000001 with all the ones that have a value x at split-second 0.0000007. Junk all the non- x brain cell activity going on between 0.0000002 and 0.0000006. (Call it noise). Now amalgamate your cherry-picked voxel with other voxels, (themselves boxes of cherry-picked data), and there you have your fMRI picture showing which region of the brain spontaneously lights up when we are thinking about love or loss or buying a house. There you have the murky world of the technicolour voxel.