1971, 2018 Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart

All rights information:

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress. A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Lapiz Digital Services, Chennai, India

Published for the book trade by OR Books in partnership with Counterpoint Press.

Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West.

paperback ISBN 978-1-944869-83-0

ebook ISBN 978-1-944869-84-7

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION TO THE FOURTH EDITION

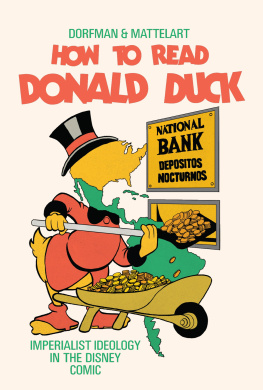

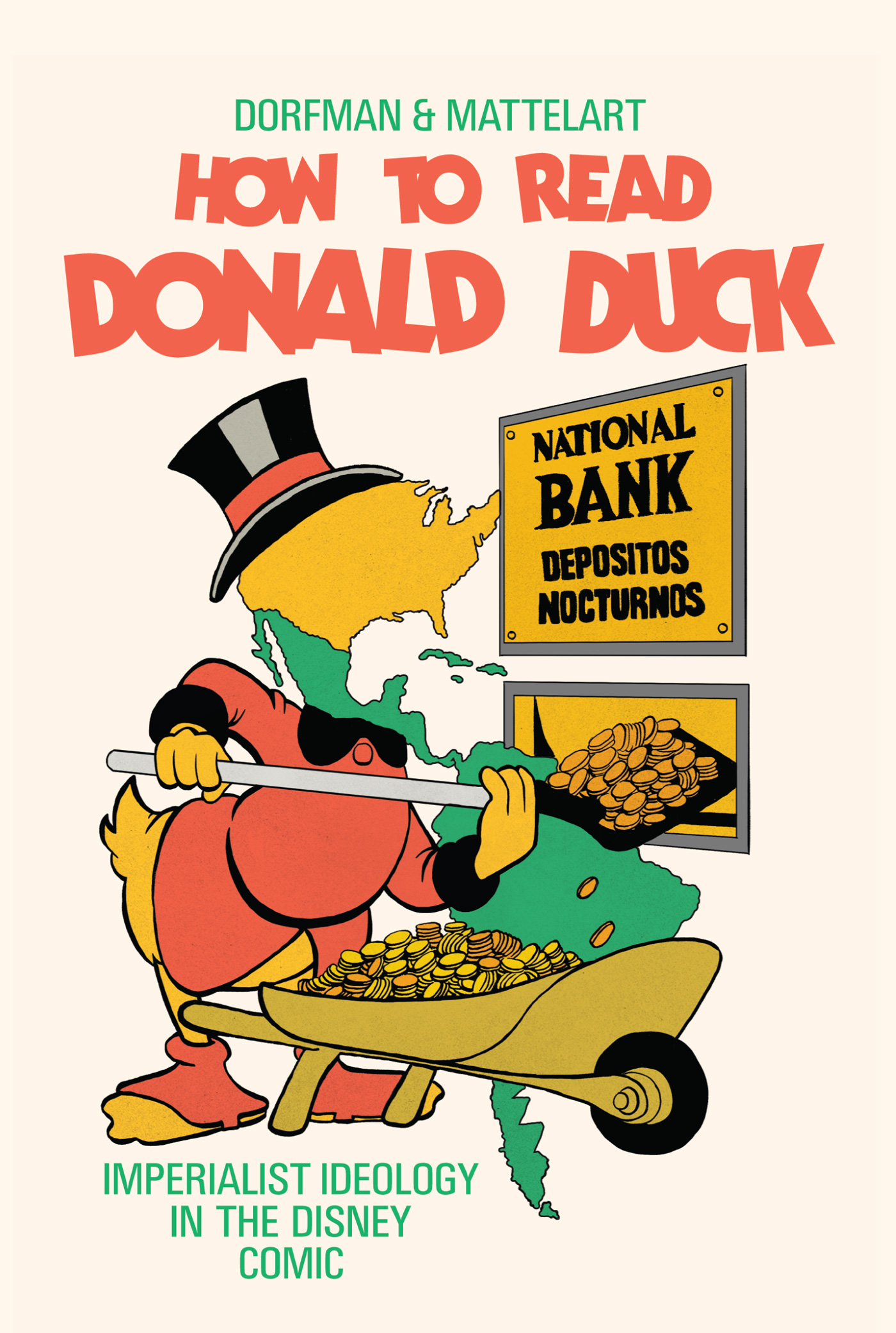

Forty-two years ago, in July of 1975, an obscure official from the US Customs Services Import Compliance Branch whose name has been swallowed by time and bureaucracy came upon a shipment from London of a book called How to Read Donald Duck , and decided that the four thousand copies that International General, its publisher in the UK, was trying to bring into the United States should be impounded, because it constituted an infringement of the Disney Corporations copyright. Considering it a piratical copying, the book was therefore detained under the provisions of the Copyright Act (Title 17 U.S.C. 106). The authorities invited the parties in dispute (the publisher and Disney) to submit briefs pending a final determination regarding the books fate.

If I have been careful to use the word detained (that Division of the Treasury Department also stated that the book had been seized and was being held in custody), it is because the violence done to that critique of Walt Disney and his imperialist ideology that I had co-written with the Belgian sociologist Armand Mattelart, the fact that it was treated as an enemy alien trying to breach the borders of the land of the free and home of the brave, was merely one more form of aggression against our manifesto. Published in 1971 in revolutionary Chile, it suffered the ravages of water and fire after the government of Salvador Allende, our constitutionally-elected president, who was trying to build socialism through peaceful means, was overthrown in a coup. In the violence that ensued, thousands of patriots were killed and hundreds of thousands more were jailed, tortured and exiled.

Water: ten thousand copies of the third edition of the book, that had become a runaway bestseller, was snatched by the Navy from a distribution warehouse and thrown into the bay of Valparaiso.

And fire. A few days after the neo-fascist takeover of our democracy on September 11, 1973 (the other 9/11), I was in hiding, lodged at a clandestine house, when I happened to see, on television, a live transmission of a group of soldiers burning books among which was my own Para Leer al Pato Donald . I was not entirely surprised at this inquisitorial blaze. In the months after we had published it, that sardonic assault upon Disneys comics and how they insidiously promoted a world vision and values inimical to any and all revolutions had touched a nerve in the Chilean right wing. I had avoided being run over by an irate motorist who shouted, Viva el Pato Donald!, I was saved by a comrade and his expert karate kicks from being beaten up by an anti-Semitic mob, and the modest bungalow where my wife and I lived with our young son Rodrigo had been the object of protests, with children of the bourgeoisie holding up placards denouncing my attack on their innocence while their parents shattered our living-room windows with some well-directed rocks.

Even so, there was something particularly disquieting about the spectacle of watching a book burning on television. Partly it was that the mediatization made the event so public and, indeed, flagrantly shameless. Somehow, I had mistakenly assumed that after the Nazi bonfires of May 1933, where tons of volumes deemed subversive and un-German had been consigned to combustion (incited by Joseph Goebbels who saw the acts as a resounding No to decadence and moral corruption), such assaults would be considered so reprehensible that, at the very least, the perpetrators would conceal their crimes from the world at large. Instead, four decades after the Nazi pyres, the Chilean military was broadcasting their furious exhibition of hatred and bigotry and making me, perhaps, the first author in history who was given the dubious privilege of gazing at his own book go up in flames through a medium that was ubiquitous, communal, pervasive and instantaneous (there had been no television, fortunately, in Hitlers time). But most alarming for me was that such viciousness against the Duck book suggested that those assailants would have no compunctions in deploying that same virulence against its author if I was unlucky enough to fall into their clutches. I have often thought that this experience helped to convince me, a month later, to accept orders from the Resistance, however reluctantly, to leave Chile in order to assist in the campaign against General Pinochet from abroad. As for Armand, who was expelled from the country, he became part of the solidarity with the Chilean cause, that was particularly massive and fervent in France. He was accompanied by his wife and fellow writer, Michle, herself a major contributor to Chiles cultural renaissance under Allende.

I carried into exile that image of our book being incinerated, and had many years to ponder its deepest and desperate meaning. We had intended to roast Disney and the Duck, vaccinate the people of Chile from the plague of the American Dream of Life and its cut-throat, greedy, voracious ideology. Instead, like Chile itself, the book had been consumed in a conflagration that knew no end, its right to a dignified existence and freedom as precarious as the lives of the workers and peasants and students who had inspired us to write it, whose own trek towards a future of liberation demanded that we liberate our mind and vision and imagine that exploitation and subjection and lies would not prevail eternally. Our book believed, as so many militants in Chile did, that society is man-made and thus can be radically altered by ordinary men and women. The fact that the military conspirators and their civilian masters in the oligarchy had been financed and aided by the American government and the C.I.A., that Nixon and Kissinger had destabilized the Allende experiment, gave to the burning of the book that stripped the United States of its traps and trappings a particularly bitter scent of defeat. We had been so sure that our words and the marching workers who stimulated them were stronger than the Empire and its acolytes. Now the Empire had proven its power, we were the ones getting roasted and digested and spat out. The revolutionaries were dead or in hiding or banished, and the Chicago Boys and their ruthless economic policies of brutal laissez-faire capitalism were unleashed on Chile, a laboratory for the Milton Friedmanesque experiments that were soon to take over England and the United States itself in the Thatcher and Reagan eras (and still reign supreme among so many conservative denizens and demons).

And yet, though so many physical copies of Para Leer al Pato Donald had been obliterated (and many more had become as clandestine as the Chilean resistance itself, waiting for the chance to resurface and walk the alamedas of Santiago again), the book itself was quite alive and being translated into dozens of languages, among them English, in the excellent version by David Kunzle. If that handbook of decolonization, using the words of the great John Berger, could not circulate in the country that had birthed it, How to Read Donald Duck might be able to penetrate the country that had birthed Walt Disney so we could continue to tar and feather him and his disciples and fans.

Next page