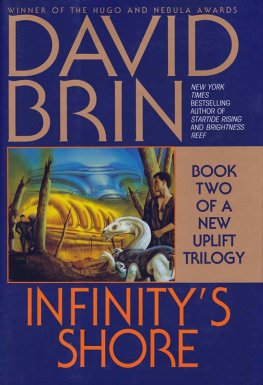

Our scrolls warn of this possibility. Our destiny seems foredoomed.

Yet when the starship's voice filled the valley, the plain intent was to reassure.

"(Simple) scientists, we are.

"Surveys of (local, interesting) lifeforms, we prepare.

"Harmful to anyone, we are not."

That decree, in the clicks and squeaks of highly formal Galactic Two, was repeated in three other standard languages, and finally-because they saw men and pans among our throng-in the wolfling tongue, Anglic.

"Surveying (local, unique) lifeforms, in this we seek your (gracious) help.

"Knowledge of the (local) biosphere, this you (assuredly) have.

"Tools and (useful) arts, these we offer in trade.

"Confidentially, shall we (mutually) exchange?"

Recall, my rings, how our perplexed peoples looked to one another. Could such vows be trusted? We who dwell on Jijo are already felons in the eyes of vast empires. So are those aboard this ship. Might two such groups have reason for common cause?

Our human sage summed it up with laconic wit. In Anglic, Lester Cambel muttered wisely--"Confidentially, my hairy ancestors' armpits!"

And he scratched himself in a gesture that was both oracular and pointedly apropos.

Lark

THE NIGHT BEFORE THE FOREIGNERS CAME, a chain of white-robed pilgrims trekked through a predawn mist. There were sixty, ten from each race.

Other groups would come this way during festival, seeking harmony patterns. But this company was different-its mission more grave.

Shapes loomed at them. Gnarled, misgrown trees spread twisted arms, like clutching specters. Oily vapors merged and sublimed. The trail turned sharply to avoid dark cavities, apparently bottomless, echoing mysteriously. Knobs of wind-scoured rock teased form-hungry agents of the mind, stoking the wanderers' nervous anticipation. Would the next twisty switchback, or the next, bring it into sight--Jijo's revered Mother Egg?

Whatever organic quirks they inherited, from six worlds in four different galaxies, each traveler felt the same throbbing call toward oneness. Lark paced his footsteps to a rhythm conveyed by the rewq on his brow.

I've been up this path a dozen times. It should be familiar by now. So why can't I respond?

He tried letting the rewq lay its motif of color and sound over the real world. Feet shuffled. Hooves clattered. Ring nubs swiveled and wheels creaked along a dusty trail pounded so smooth by past pilgrims that one might guess this ritual stretched back to the earliest days of exile, not a mere hundred or so years.

Where did earlier folk turn, when they needed hope?

Lark's brother, the renowned hunter, once took him by a secret way up a nearby mountain, where the Egg could be seen from above, squatting in its caldera like the brood of a storybook dragon, lain in a sheer-sided nest. From that distant perspective, it might have been some ancient Buyur monument, or a remnant of some older denizens of Jijo, aeons earlier-a cryptic sentinel, darkly impervious to time.

With the blink of an eye, it became a grounded star-ship-an oblate lens meant to glide through air and ether. Or a fortress, built of some adamantine essence, light-drinking, refractory, denser than a neutron star. Lark even briefly pictured the shell of some titanic being, too patient or proud to rouse itself over the attentions of mayflies.

It had been disturbing, forcing him to rethink his image of the sacred. That epiphany still clung to Lark. Or else it was a case of jitters over the speech he was supposed to give soon to a band of fierce believers. A sermon calling for extreme sacrifice.

The trail turned-and abruptly spilled into a sheer-walled canyon surrounding a giant oval form, a curved shape that reared fantastically before the pilgrims, two arrowflights from end to end. The pebbled surface curved up and over those gathered in awe at its base. Staring upward, Lark knew.

It couldn't be any of those other things I imagined from afar.

Up close, underneath its massive sheltering bulk, anyone could tell the Egg was made of native stone.

Marks of Jijo's fiery womb scored its flanks, tracing the story of its birth, starting with a violent conception, far underground. Layered patterns were like muscular cords. Crystal veins wove subtle dendrite paths, branching like nerves.

Travelers filed slowly under the convex overhang, to let the Egg sense their presence, and perhaps grant a blessing. Where the immense monolith pressed into black basalt, the sixty began a circuit. But while Lark's sandals scraped gritty powder, chafing his toes, the peacefulness and awe of the moment were partly spoiled by memory.

Once, as an arrogant boy of ten, an idea took root in his head-to sneak behind the Egg and take a sample.

It all began one jubilee year, when Nelo the Papermaker set out for Gathering to attend a meeting of his guild, and his wife, Melina the Southerner, insisted on taking Lark and little Sara along.

"Before they spend their lives working away at your paper mill, they should see some of the world."

How Nelo must have later cursed his consent, for the trip changed Lark and his sister.

All during the journey, Melina kept opening a book recently published by the master printers of Tarek Town, forcing her husband to pause, tapping his cane while she read aloud in her lilting southern accent, describing varieties of plant, animal, or mineral they encountered along the path. At the time, Lark didn't know how many generations had toiled to create the guidebook, collating oral lore from every exile race. Nelo thought it a fine job of printing and binding, a good use of paper, or else he would have forbidden exposing the children to ill-made goods.

Melina made it a game, associating real things with their depictions among the ink lithographs. What might have been a tedious trip for two youngsters became an adventure outshadowing Gathering itself, so that by the time they arrived, footsore and tired, Lark was already in love with the world.

The same book, now yellow, worn, and obsolete thanks to Lark's own labors, rested like a talisman in one cloak-sleeve. The optimistic part of my nature. The part that thinks it can learn.

As the file of pilgrims neared the Egg's far side, he slipped.a hand into his robe to touch his other amulet. The one he never showed even Sara. A stone no larger than his thumb, wrapped by a leather thong. It always felt warm, after resting for twenty years next to a beating heart.

My darker side. The part that already knows.

The stone felt hot as pilgrims filed by a place Lark recalled too well.

It was at his third Gathering that he finally had screwed up the nerve-a patrician artisan's son who fancied himself a scientist-slinking away from the flapping pavilions, ducking in caves to elude passing pilgrims, then dashing under the curved shelf, where only a child's nimble form might go, drawing back his sampling hammer....

In all the years since, no one ever mentioned the scar, evidence of his sacrilege. It shouldn't be noticeable among countless other scratches marring the surface up close. Yet even a drifting mist didn't hide the spot when Lark filed by.

Should he still be embarrassed by a child's offense, after all these years?

Knowing he was forgiven did not erase the shame.

The stone grew cooler, less restive, as the procession moved past.

Could it all be illusion? Some natural phenomenon, familiar to sophisticates of the Five Galaxies? (Though toweringly impressive to primitives hiding on a forbidden world.) Rewq symbionts also came into widespread use a century ago, offering precious insight into the moods of other beings. Had the Egg brought them forth, as some said, to help heal the Six of war and discord? Or were they just another quirky marvel left by Buyur gene-wizards, from back when this galaxy thronged with countless alien races?

Next page