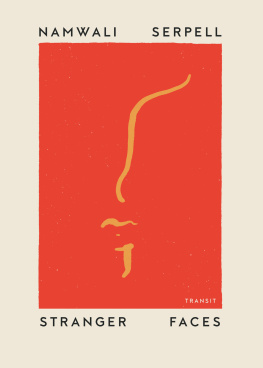

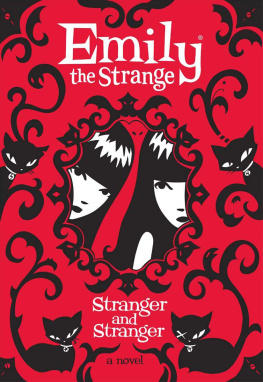

Namwali Serpell - Stranger Faces

Here you can read online Namwali Serpell - Stranger Faces full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Transit Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stranger Faces

- Author:

- Publisher:Transit Books

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stranger Faces: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stranger Faces" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stranger Faces — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stranger Faces" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

STRANGER FACES

Namwali Serpell

Published by Transit Books

2301 Telegraph Avenue, Oakland, California 94612

www.transitbooks.org

Copyright Namwali Serpell, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-945492-43-3 (paperback) | 978-1-945492-47-1 (ebook)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2020009997

COVER DESIGN

Anna Morrison

TYPESETTING

Justin Carder

DISTRIBUTED BY

Consortium Book Sales & Distribution

(800) 283-3572 | cbsd.com

Printed in the United States of America

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

for Emily Brenes and Mike Isaac

INTRODUCTION

LOOK AT ME

I know. You cant. Well, I suppose you could search my name online. If weve met before, you could picture me. If we havent, you could conjure me. Or maybe Im with you, reading these words to you in some distant future. But lets say you read those familiar words, absent my presence. Look at me. What comes to mind?

For me, this three-word sentence has some assumptions built into it. One is that by me, I mean my face. Why? There is a great deal more to me than my face, which is one of the few parts of me that I cant actually see without a reflection or a recording. When I think or say the words I or me, I rarely picture my own face. So why is the face the seat of identity? What is it about the facebe it from the point of view of biology, neurology, psychology, philosophy, anthropologythat yields that clich the eyes are the windows to the soul? In any case, look at me seems to equal look at my face.

Built into that instruction are also some assumptions about the nature of that face. Its presumably visible, close enough to see, uncovered, recognizable as a face, and impenetrablewe generally dont say look into me or look through me. To look into a face (searchingly) or through it (distractedly) would be either to go too far or not far enough in terms of seeing it. When it comes to dimension, this picture of the face corresponds to somewhere roughly between a filmic close-up and a passport photo. It is implicitly a direct view of the front of the head, not a view from the side or of the back. Another strangeness: is the front of the face really more legible than, say, the silhouette? We use both for mug shots, after all.

Embedded even deeper in the phrase look at me are assumptions about the situation in which it would be uttered. The grammar dictates a human speaker, a human listener, and a human face subjected to the view of functioning human eyes. You wouldnt say look at me to yourself or even to a mirror. We imagine a personal encounter between two people who know each other well enough for it to pass between them in a conversation. Look at me feels urgent, emotional. Prefaced by please, it becomes an appeal; by I said, it becomes an order. Between lovers, its a call to intimacy, a promise of honesty. Between enemies, its a threat of violence, a demand to be heard. Look at me vibrates with a sense of what we owe each other, that is, with a sense of ethics.

Doesnt this preclude some entities from that sense of ethical obligation? The very fact of an instruction between two humans also assumes that they are both alive and that their faces are capable of actionsspeaking and looking, respectivelyand expressions of feeling. But you might not say this sentence to a blind person, a victim of paralysis, or an animal.

The notion that human faces are recognizable, categorizable, and distinct from other kinds of faces first emerged as a scientific concept in Darwins The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). Nowadays, facial recognition is a well-studied developmental stage in babies. Neuroscientists have located a part of the brain, the fusiform face area, that lights up when we look at faces. For many, the face is the basis for sympathy, which is defined as an affinity between certain things, by virtue of which they are similarly affected by the same influence. The idea that morality is enhanced by face-to-face interaction has been promulgated by scientists since Darwin and can be summed up by the title of a 2001 article in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, Empathy needs a face.

The Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas claimed that the face is meaning all by itself. For Levinas, its not just sympathy with a face that promotes ethics. The face also subjects us to a sense of radical, unique otherness, what he calls alterity. The face shocks us into recognizing our stark difference from, and our profound responsibility for, one other.

In sum, the facewhat we ask each other to engage with when we say look at meis fundamental to how we understand ourselves. The face means identity, truth, feeling, beauty, authenticity, humanity. It underlies our beliefs about what constitutes a human, how we relate emotionally, what is pleasing to the eye, and how we ought to treat each other. All of thisontology, affect, aesthetics, ethicsrests on a specific version or image of the face. We might call it The Ideal Face. This book aims to break it.

I am by no means the first to try to take apart this picture of the face. What interests me is in fact the co-existence of these two opposed traditions: our continued belief in The Ideal Face and our persistent desire to dismantle it. Perhaps this just means that the face is an ideal before which we continually fall short. But I think we actually take pleasure in failed faces. The history of literature and art is littered not just with The Ideal Face but also with stranger faces, by which I mean both strange faces and the faces of strangers. The essays in this book take up a range of recalcitrant or unruly faces: the disabled face, the racially ambiguous face, the dead face, the faces we see in objects, the animal face, the blank face, and the digital face.

FIGURE, FETISH, ART

Stranger Faces probes our mythology of the face by treating it not as an ideal, but as a kind of signa symbol, a medium, a piece of language. A sign is made up of two parts: the sign itselflike a mark on a page or a spoken wordand whatever the sign refers to, its referenta meaning, a concept, a person. The face is similarly divided, between the surface of the face itself and whatever we think that surface means: beauty, depth, a particular emotion, humanity.

When Levinas claims that the face signifies itself and the face is meaning all by itself, he is suggesting that the surface and the meaning are fused, inseparable. I disagree. We know that signs dont always mean what they say. Signs can cease to point to referents because of willful acts of deception, distortion, or erasure. In fact, this potential disjunction between signs and referents is built in, a fundamental principle of languageand of faces, too. Studies have shown that the average person correctly assesses another persons expressions (thinking, agreeing, confused, concentrating, interested, disagreeing) only 54% of the time. Despite the belief that a face is clearer than a word, theres more variation in what facial expressions mean across culture, gender, and individuals than we might imagine.

A face is a figure. If the face is always split in twoa surface and a depth or a sign and its referentthen the stranger faces I consider intensify this disjunction. They are hard to

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stranger Faces»

Look at similar books to Stranger Faces. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stranger Faces and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.