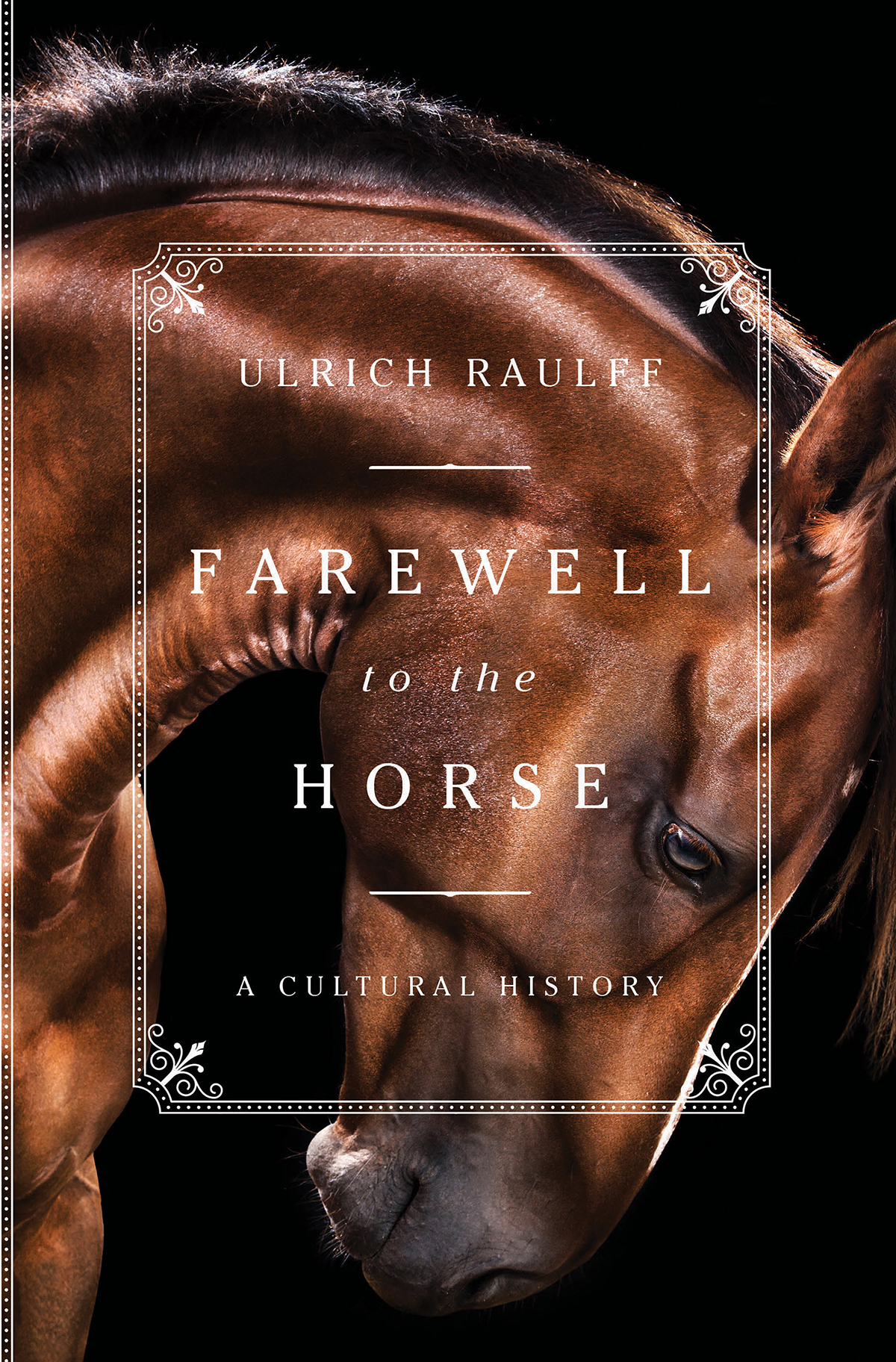

FAREWELL

to the

HORSE

A CULTURAL HISTORY

ULRICH RAULFF

Translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

Copyright 2015 by Verlag C. H. Beck oHG Munchen

Translation copyright 2017 by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp

First American Edition 2018

First published in German by Verlag C. H. Beck oHG Munchen in 2015 under the title DAS LETZTE JAHRHUNDERT DER PFERDE: Geschichte einer Trennung

This translation first published by Allen Lane in 2017 under the title FAREWELL TO THE HORSE : The Final Century of Our Relationship

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

ISBN 978-1-63149-432-1

ISBN 978-1-63149-433-8 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

Contents

PLATES

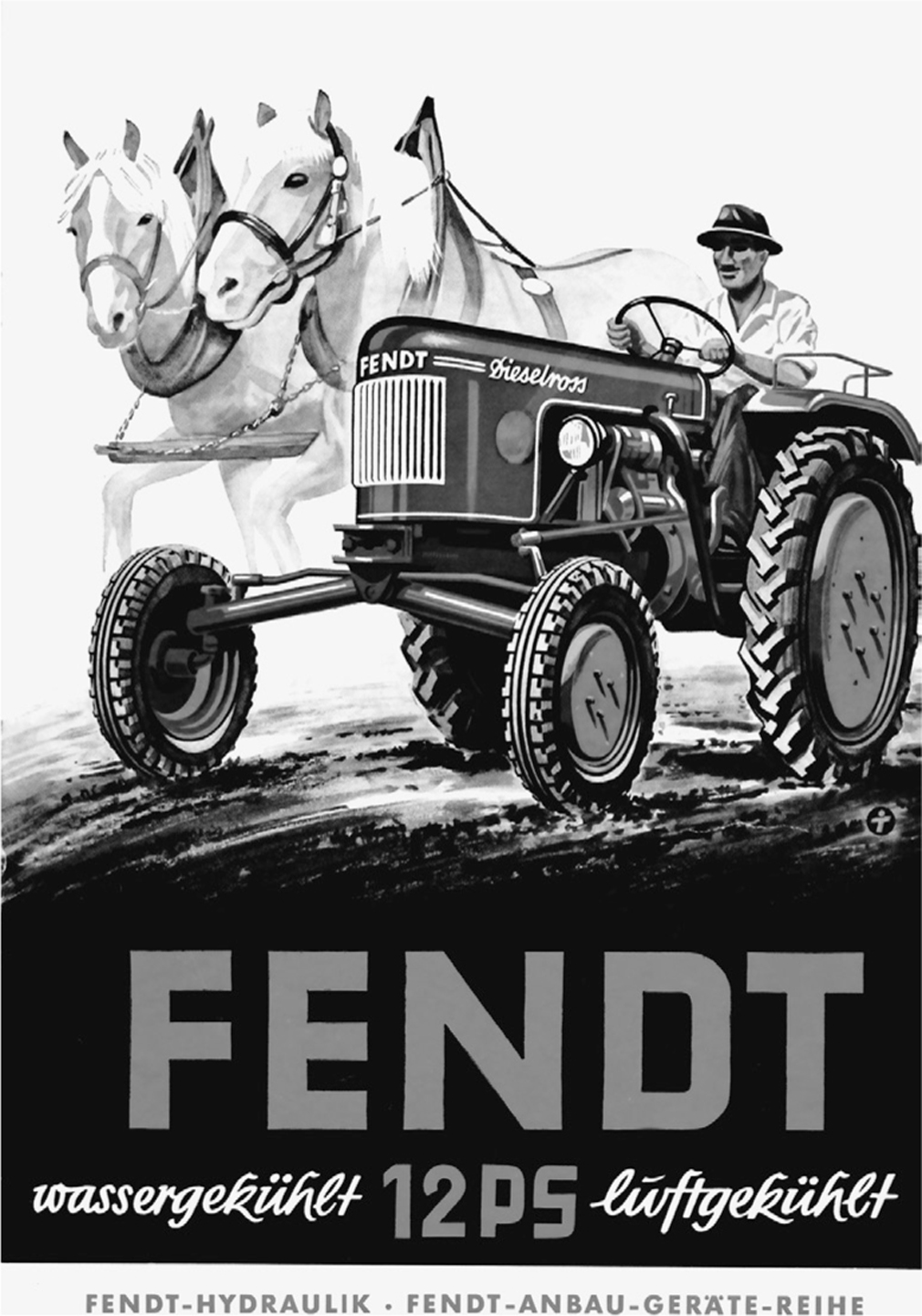

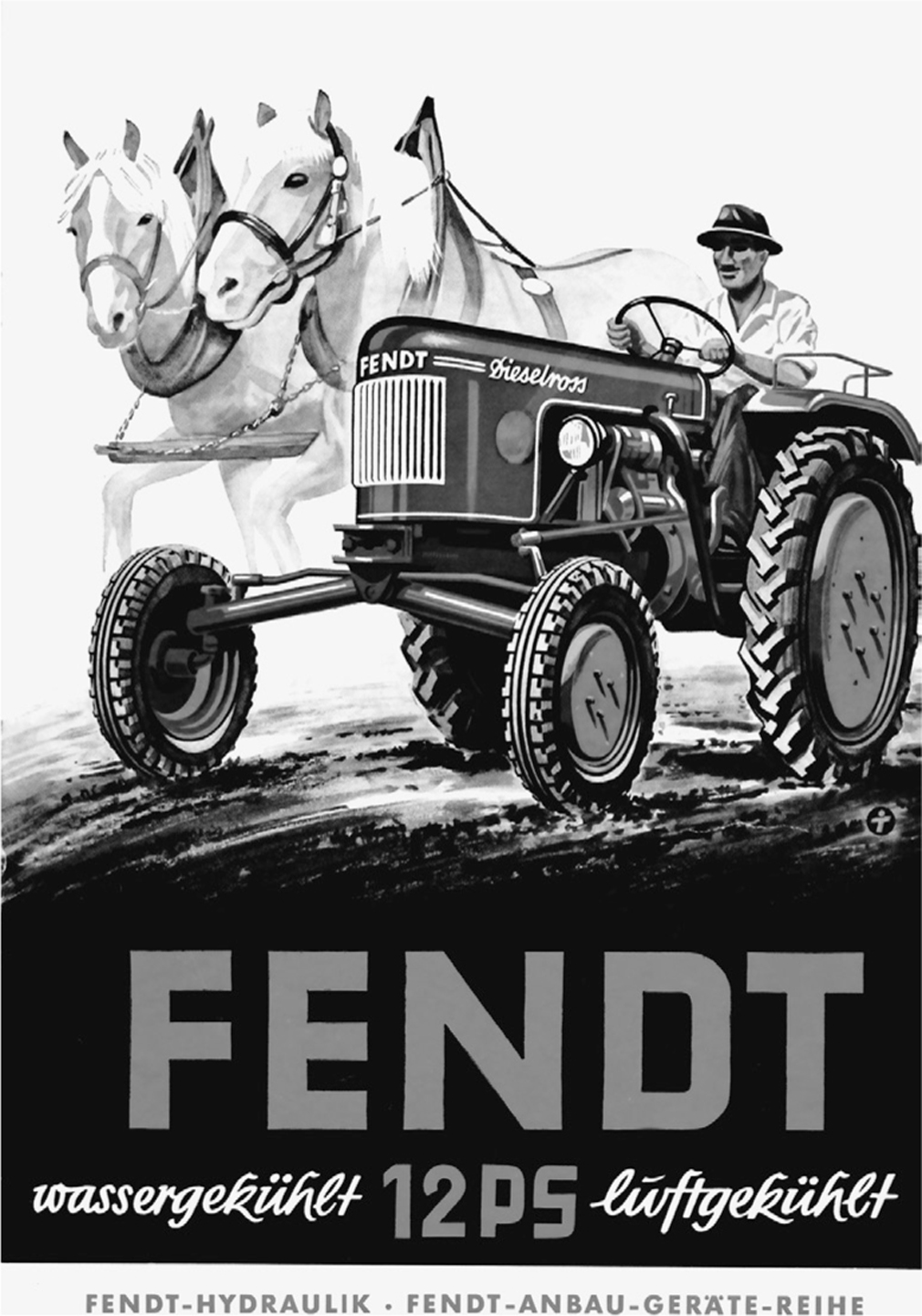

To be born in the countryside in the mid-twentieth century meant growing up in an old world. Little had changed from the way of life that existed a hundred years before. Sluggish by nature, the agricultural realm ticks over at a sleepy pace. Not so for the children of the city; their environment was one of engines and decay, the result of mechanized destruction. The countryside lagged behind, dragging its feet for nearly a century before the sudden leap into technological modernity. Farm machinery was on the increase in rural settings, certainly, whereas back in the mid-nineteenth century such machines were still rare, experimental exceptions. Over the course of the twentieth century, these machines became smaller and more practical, gradually shaking off the resemblance to medieval siege engines or huge, robotic dinosaurs. With increasing regularity they would be seen in the fields, tugged along now by small tractors; if such vehicles were known at all a century ago, they tended to be colossal steam engines. By the mid-twentieth century, tractors could muster 15 or 20 horsepower; they had short, catchy names such as Fendt, Deutz, Lanz or Faun, and with few exceptions, such as the grey Lanz, they were painted green. Looking back, they seem like fragile grasshoppers compared to the mammoths of today with their 200 h.p. engines and soundproof cabs.

Aside from these noisy pioneers of rural mechanization, whose jerky movements and clamour were at odds with the pastoral idyll of the nineteenth century, little had changed. Horses heavy Belgian coldbloods, strong Trakehners and stocky Haflingers were still the most commonly used and most widespread forms of transport and draught power on narrow, winding byways, on sloping fields and in wooded ravines. My winter memories are of the water vapour rising from their breath and their warm flanks; my image of summer is filled with the scent of their brown hair and glossy manes. I still shudder when I recall the horror I felt when I first saw the square-headed iron nails being hammered into what I thought of as the soles of their feet. It was only in church, in the Passion of Christ, that I had seen such grim scenes. Later, whenever I heard someone say they had nailed it, in the sense of successfully achieving something, I couldnt help but picture those square-headed horseshoe nails.

For farmers who still lived off the land and had not yet exchanged their modest economy for factory work, the stables were one of the smaller but nobler parts of the enterprise. Cattle, pigs and chickens were more omnipresent, more pungent and made a far greater racket; in a word, they were the plebs of the farmyard. The horses, in contrast, were rare, precious and sweet-smelling. They were more refined in their eating habits and more spectacular in their suffering: their bouts of colic were especially fearsome. Standing in their stables like living sculptures, they would nod their shapely heads, signalling distrust or suspicion with a twitch of their ears. The horses had their own pasture, to which never a cow would stray, to say nothing of the pigs or geese. No farmer would consider surrounding his horses meadow with the barbed wire which was often used to enclose sheep and cattle. For the horses, a bit of wood or a simple electric fence was sufficient to stop them escaping. One does not incarcerate aristocrats. It is enough to remind them of their word of honour.

I picture myself and my grandfather, one day in the mid-1950s, standing on a hill from where we could see our farm and the surrounding land. In the distance was a patch of deciduous woods, through which a narrow track wound its way up the hill. For a while, the silence that usually hung over the rural solitude had been ripped apart by something that resembled a hunchbacked ant slowly and noisily heaving itself up the hill. As it approached, this gigantic ant revealed itself to be one of my uncles ancient Mercedes diesel cars. The weighty vehicle drew nearer with Olympian gravitas. My grandfather made a disparaging remark about it, which included the words threshing box, and watched with growing scepticism as my cousin, the man at the helm of this beast, turned off the hard track and headed across the horses paddock straight towards us. After just a few metres on the damp grass, he lost control and the vehicle jolted sideways, skidded and made a dive for the electric fence where it became entangled and finally came to a halt by a tree stump in a cloud of dark blue smoke. As the smoke receded, the Olympian emerged into view, the thunderbolts he hurled now trapped within: ensnared by the electric fence, the car was transformed into a kind of inverse Faraday cage, its numerous metal parts conducting each surge of electricity onto the occupant within.

A fond farewell before the parting of the ways.

Horsepower contest: the diesel engine has 12 h.p.; the oat-powered engine has only 2 h.p., but it smells a darn sight better.

After all the attempts by the driver to extricate the vehicle had failed, a heavy Belgian draught horse came to the rescue. Hitched up to the diesels rear bumper, this good-natured giant heaved the wrecked vehicle back onto solid ground. Everyone knows the J. M. W. Turner painting of a steam tug puffing away as it tows a proud warship, The Fighting Temeraire , sails furled, to her final resting place in the ship-breaking yard. In our case, though, fate intervened with accustomed irony to turn the tide of history: here it was the horse, historys retired war veteran, who was called on to tow the diesel engine. The old world was back in the harness, slogging away in the service of the new.

In fact, by this point the matter had already been decided once and for all: man and horse had set off on their separate paths. Since man preferred in future to travel his path in a motor vehicle, he then had it levelled and topped with asphalt. Our equine friends were literally outrun, overtaken, left behind. Horses were consigned to that part of reality which Condoleezza Rice, former US Secretary of State, once described as the roadkill of history . For centuries, mankind had always pictured the fate of the vanquished as those who had been trampled under the hooves of the triumphant. Now, in the transition from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, it was the horse that was trampled under the hooves, or rather the wheels, of history. For most of recorded history, horses had helped man defeat his most dangerous enemy: other men. Now they were relegated to the edge of the road and to seeing their conquetor trundle off into the distance. Six hundred years of gunpowder had done nothing to move horses from their rightful place as mans most important weapon of war. But one hundred years of mechanized warfare sufficed to render them obsolete, vanquished by recent history.

Next page