INTRODUCTION

Jacques Vach was right: Nothing kills a man more than having to represent a country. With Latin American writers, the burden is even greater. It matters little in what part of the vast continent they were born. Their readers (foreign as well as national) expect them to represent Latin America. As they read their works they ask: Are they Latin American enough? Is it possible to detect in their works the pulse of the earth, the murmur of the plains, the creeping of ferocious tropical insects, or other similar clichs? Why must they always talk about Paris, London, or New York (or Moscow and Peking) instead of talking about their quaint hamlets, their endemic dictators, their guerrillas?

The Latin American writer has had to prove he is Latin American before proving he is a writer. Who would think of asking Pound to be more North American or less Provenal? Who would complain that Nabokov has left out the silence of the vast Russian steppes in his novels? Why doesnt anyone attack Lawrence for having dared to write a novel called Kangaroo? But Latin American writers are always invited to prove their origin before they are asked to show their skills. In dealing with them, criticism seems more preoccupied with geographical and historical than with literary matters. Needless to say, the whole problem is a false one. A Latin American writer must be, above all, a writer. If he has been born and lived in Latin America, the vast continent (and the dictators, jungles, plains, mountains, and guerrillas) will appear in or between the lines of what he writes.

The confusion is resilient, nevertheless. As Marxist criticism took decades to realize that Kafka had anticipated the horrors of the concentration camps in some of his novels and tales, LatinAmerican Marxists have been late in seeing that Borgess The Lottery in Babylon is an accurate description of his chaotic Argentina. Theyve also been slow in recognizing the surrealistic personae of Vallejos and Nerudas poetry as valid metaphors for Latin Americas alienated man: a man who until quite recently could not find roots in his own land nor discover as an exile a place he could truly call his own. Too sophisticated for many of the developing Latin American countries, he used to feel too provincial in Europe or the United States. Things have changed now in many countries, but writers still feel the burden of alienation in a large part of the continent. And Vallejos and Nerudas anguish are very relevant today.

But folklore, literary geography, anthropology, and sociology continue to lure many critics. Some years ago, Lionel Trilling said that Latin American literature had only an anthropological value (Borgess best stories were already published). Even today many believe that One Hundred Years of Solitude is the best Latin American novel because it confirms, apparently, the folkloric prejudiceeven though Garca Mrquezs novel is mythical in a sense that only a reader of James Joyce or Joseph Campbell can understand.

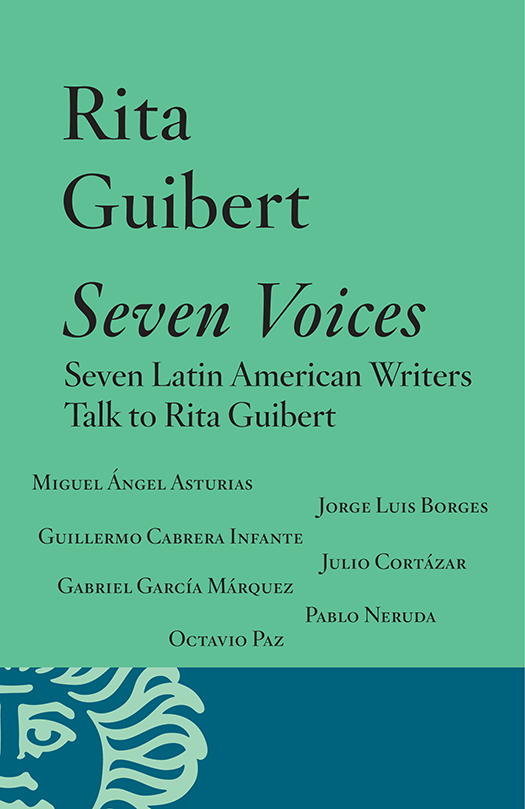

Seven Voices makes it plain that Latin American writers want to be read, first, as writers, and judged on literary terms. Armed with patience, a tape recorder, and some notebooks, Rita Guibert has hunted down, on three continents, seven of the most important writers of Latin America. Unlike many of her colleagues, she has not attempted to extract programmed answers to equally programmed questions. Her questions are meant to unleash the flow of conversation. Her secret is knowing how to listen. The voice of each of the writers is fully revealed in these pages. A common pursuitthe craft of fiction, the art of poetrylinks them beyond idiosyncrasies of age and points of view.

But their seven voices could not be more different. And the differences are not only of temperament and ideology; they go deeper. While Pablo Neruda speaks without reserve and lets the words flow conversationally, Octavio Paz takes notes before speaking, answers with the most extreme caution, and then phrases and rephrases his words until they have the bite of his critical essays. But that difference in their way of talking is also a difference in their way of writing poetry, and even in their way of life. Again, it is easy to contrast the slow, rhetorical tone of Miguel Angel Asturias with Gabriel Garca Mrquezs quick and playful delivery. The public hostility between the two (which is revealed in the couple of digs they give each other) is more than casual: Asturias belongs to that generation which believes literature to be something sacred; Garca Mrquez represents that wishing to be free of all solemnity. Even in two writers who have so much in common, like Borges and Cortzar, opposing styles are apparent. Borges answers all questions orally and never drops the conversational tone. Cortzar carefully edits his answers to a written questionnaire and turns the interview into a pretext for an essay in which each word has been painstakingly premeditated.