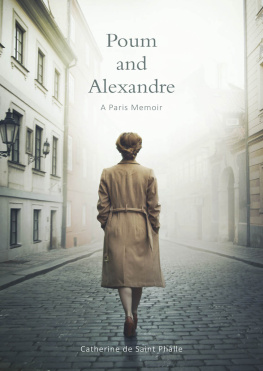

Poum

and

Alexandre

A Paris Memoir

Poum and Alexandre

A Paris Memoir

Catherine de Saint Phalle

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

www.transitlounge.com.au

First Published 2016

Transit Lounge Publishing

Copyright 2016 Catherine de Saint Phalle

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

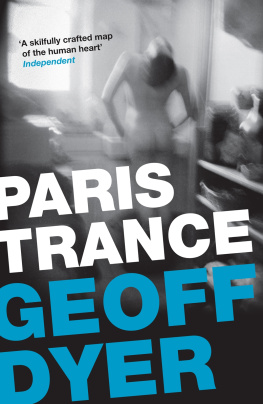

Cover image: Mark Owen/Trevillion Images

Cover and internal design: Peter Lo

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the

National Library of Australia www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN: 978-0-9943957-9-5

lamour de ma vie, Paul Croucher

POUM

ALEXANDRE

POUM

AND

ALEXANDRE

ARLES

My mother, Marie-Antoinette, likes strange and sad things. It makes me want to save her from the rue du Cirque, where she lives, behind the gardens of the lyse palace. I dream of taking her away from the concierge who frightens her, the family that seems to dislike her, and the nuns of my school who terrify us both. I often imagine us in an empty house nestling in an overgrown garden. I have seen it in Sussex where I am often sent. I will paint it and repair it and make it very welcoming. We will live there together, my mother and I, in this secret house where she will be happy at last and talk to me and explain who she truly is.

Hardly anyone ever calls my mother Marie-Antoinette, which is her real name. They call her Poum instead. When she was a small child, she sat on the top step and went down the stairs on her bottom, saying poum, poum, poum. From then on Poum is the name her family gave her and she answers to no other. I am the only person in the world who doesnt use either name. From the start our relationship lives on rarefied air.

Is the lady coming to see us today? I ask Sylvia before Poum swarms into our bedroom in a flutter of wings and words. Sylvia has looked after me since I was two years old, and when we are not in Sussex with the Lees, her parents, whom I call Mummy Joyce and Daddy John, we are back in my mothers apartment in Paris. Sylvia is eighteen when she first takes me on. She is very big and quiet. She has passed exams to look after children. My mother, who has never sat an exam in her life, consults her like a doctor or a child whisperer, and leaves me entirely in her capable hands. There are several other people on my case before that but I cant remember them. The last one is a pretty Irish girl who stays a year. She likes to drink and party and leaves me alone without notice for nights on end. My parents are quite desperate when she leaves because shes such a sunny personality. They miss her. Sylvia is less fun, but more reliable, they reason sadly.

To me, it is my parents quarter that is not much fun. It is staid and residential and seems to say: Only grown-ups live here. The grey buildings have been standing there forever behind their united front. There are hardly any children. If I see a child I fantasise about him or her for weeks. The rare ones in our street are whisked inside, as if meeting another child could be contagious.

When Marie-Antoinette comes into our room, she pinches my cheek and covers my face with pecks. I am a slippery parcel. Her nails dig into my arms. Then suddenly shes gone and Sylvia and I are left looking at each other. Marie-Antoinettes presence is like putting the music on too loud or turning on too many lights at the same time. It takes us a while to catch our breath again. I know she is my mother, but at that time mother is just a word.

I try to map her out, but it is only when I go out on a limb that she appears out of the mist in which she surrounds herself. Once she tells me she has dreamt of flowers and leaves locked in plexiglass living things forever beautiful, unchanging. I am only a child, but it feels like a nightmare to me. How can they breathe? Yet something in my heart wonders if she isnt one of those beautiful, unchanging leaves or flowers that have to stay apart, separate and untouchable, in order to survive. I never know when Poum will share these isolated thoughts with me, like bits of morse code, even if the rest of the message is eaten by the wind and the hoarse cries of gulls. Our intimacy is about distant things, about the moon, dreams or The Odyssey, of which she knows whole swathes by heart. As I grow older, she will sometimes glance at me across a crowded room or even just blink when someone says something frightening or sad. These subtle acknowledgments of a mysterious, common understanding are rare, but I remember them like messages from outer space.

Poum is not from outer space. She is part Russian, with a Russian great-grandmother, and the rest of her is Old Europe with a Spanish father and a French mother. She behaves like a memory long before I try to remember her. Maybe she knows her whole being can fall apart at any minute, and that all the kings horses and all the kings men couldnt put her together again. Maybe her puzzle needs to be enclosed in order for her to stay whole. I always imagine she is busy keeping the bits of herself in the boxes she collects. A tiny ivory one with its minute lock and key, a heavy pewter one, an ebony one strapped like a chest, a round silver one with a crown, a copper one with a white powdery lining empty boxes that she pats, opens and closes. She seems to be begging, like Pandora, for everything to return to its safe place. These boxes feel magical to me. I wonder why they are always empty. I never see her put anything inside them. I am not allowed to touch them; nor is my father. He is too clumsy, she says. In fact, they are both clumsy. My father, Alexandre, is clumsy like an elephant, while Marie-Antoinette is clumsy like a bird. She drops, spills and breaks things and exclaims several times a day: All I wished to avoid has happened! However, when she touches her boxes, her fingers have eyes that know where to go, seeing their way lightly and cleverly. My father and I both watch her when she moves her boxes and hold our breath as if something were going to happen.

When I am suddenly away from my parents, they are the fairytale I tell myself every day to believe in. People whisper about them as if they arent quite true, just like Father Christmas and Little Red Riding Hood. People love to explain that no one lives at the North Pole, its much too cold, and no, Little Red Riding Hood is not a real little girl and there arent any wolves left in Sussex. I am left with Sylvias parents, Daddy John and his wife, Mummy Joyce, for months on end in their little house that is nowhere near outer space but in Bognor Regis, Sussex, in the south of England, by the sea. That is where the abandoned house with the overgrown garden is just down the road from them. I even secretly borrow a pot of paint and a paintbrush from Daddy Johns shed to paint it white. I go there to do my work whenever I can. They think I am playing in the field.

For John Lee, my parents have too much money, money that my father earns swiftly and loses just as swiftly. My parents are casual about material things, which makes them look rich even when they are finding it hard to pay the bills. It gives them an irresponsible, childlike aura. They are not wholly convincing. Their enthusiastic voices soar in the Lees little English cottage and are soon confused with the exhaust pipe of their car driving away. The Lees and I are left to carry on with our day. Once, on a whiff of my parents impending arrival, I crouch a whole afternoon on the narrow ledge of the Lees front porch from where I can see far down the road. I wait until the sun dies in the grass and I am called in for bedtime but they dont come.

Next page