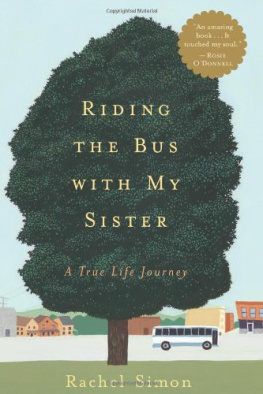

Copyright 2002 by Rachel Simon

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Visit the authors Web site: www.rachelsimon.com.

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

ISBN 0-618-04599-6

e ISBN 978-0-547-34484-3

v5.0115

For Cool Beth

Authors Note

Some of the individuals who participated in this story asked me to change their names. In the interest of honoring those requests in a way that would not tempt readers to sort out the real names from the invented, I chose an egalitarian approach and altered everyones name, except for my sister Beths and mine. In addition, I changed details about the location to help preserve Beths privacy.

JANUARY

The Journey

Wake up, my sister Beth says. We wont make the first bus.

At six A.M. on this winter morning, moonlight still bathes her apartment. Shes already dressed: grape-juice-colored T-shirt and pistachio shorts, with a purple Winnie-the-Pooh backpack slung over her shoulder. I struggle awake and into my clothes: black sweater, black leggings. Beth and I, both in our late thirties, were born eleven months apart, but we are different in more than age. She owns a wardrobe of blazingly bright colors and can leap out of bed before dawn. She is also a woman with mental retardation.

Ive come here to give Beth her holiday present: Ive come to ride the buses.

For six years, she has lived on her own. In her subsidized apartment, a few blocks off the main avenue of a gritty, medium-sized Pennsylvania city, each of her days could easily resemble the nextshe has a lot of time, having been laid off from her job busing tables at a fast food restaurant. She has enough money to live on, as a recipient of government assistance for people with disabilities.

But Beth also has something else: ingenuity.

This trait isnt generally ascribed to people who live on the periphery of societys vision. Like indigent seniors, people with untreated mental illness, and the homeless, Beth is someone many people in the mainstream dont think much about, or even see.

Six months after she moved to her fifth-floor apartment, she realized that she was lonely, and had consumed all the episodes of The Price Is Right and All My Children that she could tolerate. So one day she decided to ride the buses. Not just to ride them the way most of us do, and which her aides had trained her to do a few years before. She wasnt interested in something as ordinary as getting from one location to another. She wanted to ride them her way.

It was, Beth recalls, October 18, 1993, when, for reasons she cannot remember, she first picked her monthly bus pass off her coffee table. Then she pressed the first-floor button in her high-rise elevator, walked through the vestibule to the street, hailed a bus on the corner, climbed the steps toward the driver, settled into a seat, and looped through the city from dawn to dusk, trying out one run after another, bus to bus to bus. Soon she was riding a dozen a day, some for five minutes, others for hours, befriending drivers and passengers as she wound through the narrow streets of the city and its wreath of rolling hills. Within weeks she could navigate anywhere within a ten-mile radius, and, by studying the shifting constellations of characters and the schedules posted weekly in the bus terminal, she could calculate who would be at precisely which intersection at any moment of any day. She staked out friendships all over the city, weaving her own traveling community.

Beths case manager had not suggested this, nor had Regis and Kathie Lee, nor even Beths boyfriend. This idea was hers alone.

We hurry down Main Street, the moon setting behind the buildings. My guide, whose fuzzy brown hair is still wet from her morning bath, points out the identifying numbers on bus shelters, the scowls of grouchy drivers. She wears no watch, telling time instead by the buses.

We dart into the downtown McDonalds, already, at six-thirty A.M. , filled with early risers: clusters of the elderly playing cards, solitary office workers bent over newspapers. Beth orders coffee, though she doesnt drink coffee, palming out the eighty-four cents before the server asks.

Then we bolt into the dawn, making a beeline for a bus shelter. Head craned down the street, Beth giggles as she once did when I took her to a Donny Osmond concert: thrilled, in her element. She clutches her yellow radio and a tangle of key chainstwenty-nine, by her countCookie Monster, smiley faces, peace signs, which hold a total of two keys. She does a drumbeat on her laminated bus pass, stickered 000001. Every month she renews it, arriving first in line at the sales window. That sticker is her private coat of arms, proof that shes queen of these routes.

Our first bus draws up to the curb. The driver, Claude, throws open his door as if welcoming us to his house. Beth clomps aboard, arm thrust forward with the coffee. He takes the steaming plastic cup, then thumbs four quarters into her hand. Our agreement, he explains to me.

Then she spins toward her seatthe premier spot on the front sideways bench, catty-corner from his, so shell be as close to him as possible. I sit beside her; as a suburbanite who relies on my car and the occasional commuter train, it is my first time on a city transit bus in years. We pull out, past working-class row houses, a Christian lawn ornament store, a farmers market, an abandoned candy factory, Asian grocers. Short hair, just beginning to gray, fans out from underneath Claudes drivers cap. Beth announces that hes forty-two, with a birthday coming soon. He laughs as she offers the exact date and then explains how he likes to spend his birthdays. She remembers everything, he says.

He asks if shell change into her flip-flops should this chilly day become as balmy as the forecast predicts. If iz over forty, she replies, you know I will. He tells me they jam with her radio when the bus is empty. Real loud, she adds. They recall some trouble with a rider months ago. She was mean, Beth says indignantly. Claude agrees, and recounts the altercation, in which a passenger vehemently challenged his knowledge of upcoming stops, and which culminated, after the malcontent had finally exited, in Claudes relief that Beth was sharing the ridehe had someone who could sigh along with him.

Moments later, we pass Beths boyfriend on his bicycle. Also an adult with mental retardation, Jesse has paused at a crosswalk, his maple brown face pointing straight ahead, his blind left eye looking milky in the light, sun glinting off the helmet Beth long ago convinced him to wear. The decade theyve been together is more than a fourth of their lives. Claude picks up his intercom mike and calls out, Hello, Jesse! Jesse looks over. We twist around in our seats, and his mustached face brightens as we wave.

All day, when we mount Jacobs bus, Estellas, Rodolphos, one driver after another greets Beth heartily. They tell me she helps out: reminds them where to turn on runs they havent driven for a while, teaches them the Top Ten songs on the radio, keeps them abreast of schedule and personnel changes, and visits them in the hospital when theyre sick. She assists her fellow passengers as well, answering questions about how to reach their destinations, sharing their consternation when the bus halts for double-parked delivery trucks, carrying their third bag of groceries to the curb.

In return, many riders smile hello to her and ask how shes doing; many drivers are hospitable, even affectionate. Jacob asks if she has gotten a new winter coat and if the homeless woman who clashed with her last month has bothered her again. Jack slips her money for soda. Bert squawks out songs, making her laugh at his jaggedy tunes.

Next page