Contents

Guide

Page List

i I think muchly of what little we have done together: and doubt not we shall do more & better. Onward & upward, as the balloon said when it broke the wire. Denis Glover, 1944

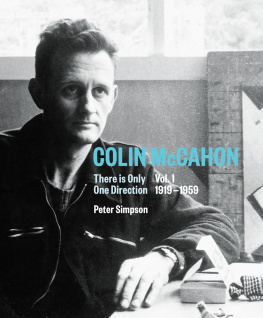

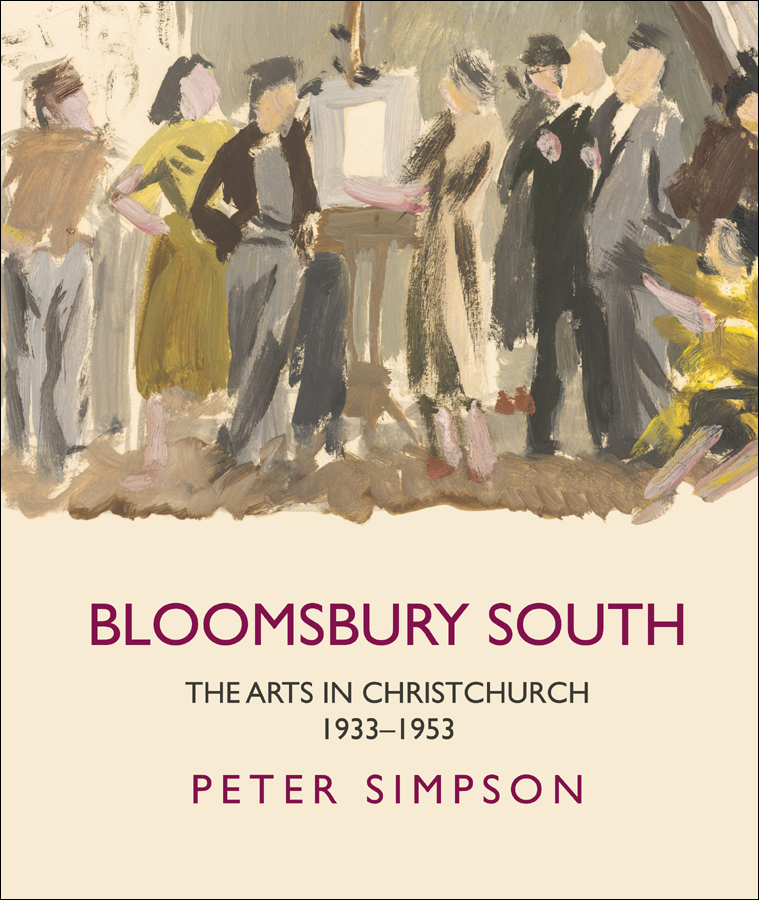

For two decades in mid-century Christchurch, New Zealand, a cast of extraordinary men and women remade the arts. Between 1933 and 1953, Christchurch was the home of Angus and Bensemann and McCahon, Curnow and Glover and Baxter, Marsh and Lilburn, not to mention The Group, the Caxton Press, the Little Theatre, Landfall and Tomorrow. It was a city in which arts of different forms were deeply intertwined, where painters lived with writers, writers promoted musicians, and artists developed a powerful synthesis of modernist influences and assertive nationalism that shaped the countrys cultural life.

In this gorgeously illustrated book, Peter Simpson tells the remarkable story of the rise and fall of this Bloomsbury South. Simpson brings to life the individual artists of the time their talents and their passions but he also takes us inside the scenes that they created together: Ursula Bethell and her coterie of younger writers and artists; Denis Glover and Leo Bensemanns exacting typography at the Caxton Press; the yearly exhibitions and aesthetic clashes of The Group; Ngaio Marshs Shakespearian re-creations at the Little Theatre; Charles Braschs patronage and literary vision; and the developing friendship of temporary Christchurch residents Colin McCahon and James K. Baxter. By the early 1950s, much of this brilliant scene had dispersed. Simpson re-creates and attempts to account for a Christchurch we have lost, where a dynamic group of people collaborated to create a distinctively New Zealand art which spoke to the condition of their country as it emerged into the modern era.

ii Published as part of the

Gerrard & Marti Friedlander

Creative Lives Series.

iii BLOOMSBURY SOUTH

THE ARTS IN CHRISTCHURCH 19331953

PETER SIMPSON

iv For Helen, who has been with me from start to finish

v Contents

vi

vii PREFACE

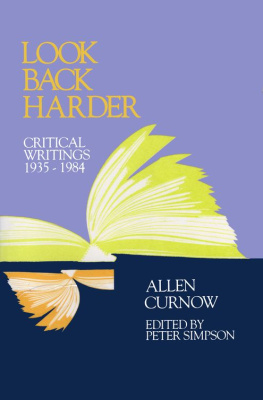

The origins of Bloomsbury South go back more than half a century to when I first lived in Christchurch, from 1960 to 1968 (I spent a later period there from 1976 to 1992). I have now lived in Auckland for almost as long as I did in Christchurch. Like several of the people discussed in this book, including Allen Curnow, Colin McCahon and Bill Pearson, I was a South Islander who came north to Auckland for a job.

I first moved to Christchurch in 1960 to attend university. The University of Canterbury, newly independent of the University of New Zealand, was a small institution of about 3000 students (it is now around 15,000), mostly packed into colonial neo-Gothic stone buildings on the central city site bounded by Worcester, Montreal and Hereford streets and Rolleston Avenue, just as it had been some 30 years earlier when Denis Glover, Rita Angus, Douglas Lilburn and many others who figure in this book were students. By 1976, when I returned to Christchurch after a period overseas, the university had relocated to Ilam in the north-west of the city. The old university site with its cloisters, lawns and winding stairs had meta-morphosed into the Christchurch Arts Centre, now gradually being restored after the devastating earthquakes of 2010 and 2011.

Because I majored in English, I had the good fortune to study under a group of gifted teachers who made up the English Department in that era. They included Professor John Garrett, a Canadian and a charismatic reader of poetry; Associate Professor H. Winston Rhodes, calm and quizzical, who gave marvellously searching lectures on nineteenth-century novels; Dr Ray Copland, whose memorably witty lectures on eighteenth-century fiction reduced lecture rooms to helpless laughter; silver-haired and impeccably suited Lawrence Baigent, whose lectures on Shakespeares tragedies were delivered with polished eloquence; A. W. (Archie) Stockwell, large and kindly, a gentle expositor of the Romantic poets; and Charles Spear, an owl-like, quietly spoken and red-cheeked medievalist and poet. All have smaller or larger parts to play in the pages that follow. All, except Garrett, regularly reviewed books for Landfall. Strangely, almost the only writing published by these English literature specialists concerned New Zealand literature.

Before heading overseas I taught for several years alongside the older men (they were all men) who had been my teachers. I gave lectures in the Great Hall where Curnow and Lilburn had performed Landfall in Unknown Seas three decades earlier; I tutored for Rhodes when he gave the first full course devoted to New Zealand literature in 1966; Baigent regaled me with stories about printing James K. Baxters Beyond the Palisade in 1944, a copy of which I bought over the counter from Leo Bensemann at the Caxton Press in Victoria Street; Stockwell gave me a bundle of priceless early Caxton publications; Spear told me how his poems were written in his sleep.

As I came to know them better they were a hospitable group who socialised together and often invited younger staff to their homes for dinners or parties I met others from the Christchurch art scene who were their friends, such as Doris Lusk, Bensemann and Charles Brasch. Through these contacts I became increasingly aware that, in previous decades, there had been a golden age in the arts in Christchurch which, by the 1960s, had definitely if viii mysteriously faded. Some remnants from that earlier era were still active and vital. The Caxton Press published a few new books every year, including volumes by Brasch, Ruth Dallas, Frank Sargeson and Maurice Duggan. Landfall, edited by Brasch as it had been since 1947, still appeared each quarter. The Pegasus Press, also Christchurch based, published collected editions of poems by R. A. K. Mason, Glover and A. R. D. Fairburn, and novels by Janet Frame, such as Faces in the Water and The Edge of the Alphabet. The Group, whose paintings hung on the walls of my older colleagues, still held exhibitions every spring, which I frequented, becoming fascinated in particular with what new wonders Colin McCahon and Toss Woollaston would serve up each year.

But where were the poets? Of the 25 living poets in Curnows Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse (1960) only two Spear, who had published nothing since 1951, and Paul Henderson (the pseudonym of the novelist Ruth France) lived in Christchurch, as compared with seven in Wellington and eight in Auckland. It was the same story in fiction. Of the twelve story writers in Landfall Country, published in 1962, not one lived in Christchurch, whereas eight were in Auckland. Back then I pondered the contrast between the scintillating past of Christchurch and its comparatively drab present. Why had the golden weather come to an end? This book is an attempt to answer that question.

Just as the contrast between the Christchurch of the 1930s and 1940s with that of the 1960s was striking, so is that between the city I knew in the 1980s and the Christchurch of 2015. The drastic earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 changed the city for ever. Although I had lived in Auckland for nearly 20 years, the earthquakes affected me directly in a small way apart from sad and troubling disruptions to the lives of family and friends.