B ut its so flat, some said. Wont you miss the hills? Others looked kind but a trifle pitying. There were polite comments about nice gardens. One wise friend, though, just smiled when I told him I was returning to my home town of Christchurch after twelve years in Wellington: Turangawaewae, he said. Exactly. I had loved the jumbled vigour of the capital, so engagingly and raffishly different from the ordered streets in which I had grown up, but, increasingly, I had missed the South Island. I was ready to go home.

And when I returned to the city where I have lived for most of my life, I saw it with fresh eyes. I understood again the power of familiar landscape. I had longed for a horizon filled with the uncompromising rocky outlines and lion-gold summer tussock of the Port Hills, not the gorse-covered or dark evergreen slopes behind Wellingtons crowded skyscrapers. I had been hankering for a real botanic garden the much-vaunted tulips and magnolias above Glenmore Street could never compensate for the glowing flower borders beside Rolleston Avenue or the towering trees outside the Canterbury Museum. I was glad to walk again in the Arts Centre, formerly the University of Canterbury, whose grey Gothic stones and worn steps seemed the next best thing to Oxford when I was a 17-year-old student. Most of all, though, I rediscovered the Canterbury sky, that immense curving space which more than compensates for the flatness of the plains beneath. I am a third-generation South Islander on one side of my family, fourth generation on the other. This is the place where I belong.

And so, when it came to choosing the pieces for this anthology, I looked for the elements that make up the Christchurch I have known, as a child and an adult. My ancestors were not wealthy, but much is often made, in this most English of cities, of the well-heeled C of E settlers who arrived on the First Four Ships to settle the province. The chapter from Sarah Amelia Courages 1896 novel, LightsandShadowsofColonialLife, recounts, with engaging candour, her first reactions to the colony. Since she only flimsily disguised the neighbours of whom she wrote without flattery, she became the object of local fury and much of her small print run was burnt. Stevan Eldred-Griggs irreverent story, Where Bawds and Whores Do Churches Build, pokes fun at the Canterbury Pilgrims and the citys Anglican beginnings.

When detective writer and theatrical pioneer Ngaio Marsh was a child in the 1900s, Christchurch was still a developing settlement. As she remembers in her autobiography, a move from Fendalton to Cashmere (and the house where she spent her New Zealand life) required a spring-wagon and an interminable journey. After many years overseas, poet Mary Ursula Bethell, too, made her home on the hills, where southerly gales could cause havoc in her beloved garden. Wellington does not have a monopoly on wind.

With vituperative relish, Denis Glover offers a picture of Christchurch as he saw it in the 1930s (and many people still perceive it today) a class-ridden, po-faced, tight-lipped market town, where, as the old joke goes, the first question you will be asked is, What school did you go to? But for John Bluck, former Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, who first came south as a student in the 1960s, Christchurch represented freedom. It never became, then or later, the smugly prim and parochial city that many other outsiders have found it. Although columnist Joe Bennett is not Canterbury-born either, he understands as well as any native that the green spaciousness of Hagley Park is the soul of this city. More organised horticulture can, however, be taken rather too seriously in the garden city, as A.K. Grant delightfully observes.

Kate Flannerys story, Old Faithful, speaks of the childhood Christchurch I remember, the familiar department stores, the rush and heat of Christmas shopping, the reliable comfort of tradition and family.

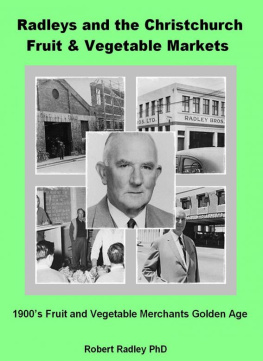

But Christchurch is not all leafy suburbs and security. This is also an industrial city, a city that is home to workers and students, a city with a working port. Stevan Eldred-Grigg, James K. Baxter, Frankie McMillan, Gordon Slatter and Owen Marshall reveal an edgier, less privileged and settled face of Christchurch and its neighbour, Lyttelton.

When I lived in Wellington, I enjoyed a stroll round Oriental Bay on a sunny afternoon, or catching glimpses of the harbour from downtown streets, but I never felt at home on its wild southern beaches. I had, after all, grown up with the tranquil bays and bare volcanic hills of Banks Peninsula. I was used to Sunday afternoon drives across the causeway to Sumner where there would be an ice cream and the challenge of scaling Cave Rock (now far smaller than it used to be). James Courage, Fiona Farrell and Hone Tuwhare, in their different ways, speak of Christchurchs often overlooked connections to the sea.

Much more familiar and accepted is the citys place on the Canterbury Plains, where the norwester tears over the mountains, bringing with it dust, bad temper and hayfever, and the summer heat bakes the paddocks to shimmering aridity. Christchurch has strong links to its province, and to the small towns that straggle beside those long, straight roads. Jennifer Maxwell, Mike Johnson, Owen Marshall and Robin Muir all write of this landscape with knowledge and affection.

The Arnold Wall poem at the end of the book is well known but, to me, it vividly evokes a flat city that has hills behind it and mountains beyond; a city that, although it is now more often folded in smog than mist, still has above it a vast wing-winnowed clime of Heaven; a city where, in winter, the street just round the corner from my house is closed with shining Alps.

Anna Rogers

Couchedinthehiddenchambersofthebrain,

Ourthoughtsarelinkedbymanyahiddenchain,

Awakebutone, andlo!Whatmyriadsrise,

Eachstampsitsimageastheotherflies.

Samuel Rodgers

W e took rooms for some days at an hotel called the Mitre, an ugly wooden building, the best in Lyttelton at the time, and in which we were tolerably comfortable. Colonial manners struck us unpleasantly at first; the curt, off-hand manner in which some of the people spoke and acted was strange and unpleasant; they were not uncivil, but brusque and familiar to a degree. First impressions are supposed to be lasting, and to this day I have never got to like colonial manners.

In the evening of the day that we landed my husband and I went out for a stroll. We walked round the side of a steep hill overlooking the harbour, which I now know to be Governors Bay road. A short distance from the road, we went up a blind gully filled with tree ferns and cabbage trees. We were attracted thither by a blaze of scarlet; it was a house, a rough-looking shanty, built of slabs of wood stuck endwise in the ground as closely as the rough edges could be placed together. It stood on the banks of a running creek and was planted thickly round with scarlet geraniums, a mass of colour. It was quite an object of beauty in its way. There for the first time we saw a eucalyptus or gum tree, some very fine specimens of which were growing near this house; one, I was told, was fifty feet high, most of them being about ten feet in girth. They cannot be called handsome trees except for size, the colour of the leaf being a dull bluish green; but its medicinal uses are many. Indeed, it is very valuable as a medicine, as I have proved on many occasions, the only drawback being its pungent odour it is like strong turpentine and is to some people very unpleasant.