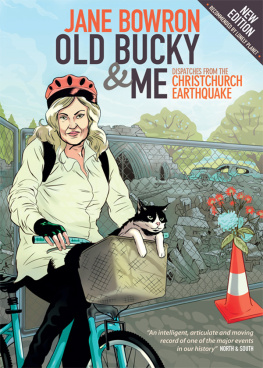

First eBook edition published in 2012 by

Awa Press, Level 1, 85 Victoria Street

Wellington, New Zealand

Copyright Jane Bowron 2011

Columns in this book originally appeared in The Dominion Post and The Press . This edition includes 26 new columns not included in the first edition published in 2011.

ISBN 978-1-877551-45-1.

The right of Jane Bowron to be identified as the author of this work in terms of Section 96 of the Copyright Act 1994 is hereby asserted.

Copyright in this book is held by the author. You have been granted the right to read this e-book on screen but no part may be copied, transmitted, reproduced, downloaded or stored or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system in any form and by any means now known or subsequently invented without the written consent of Awa Press Limited, acting as the authors authorised agent.

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

www.awapress.com

To the Aged Parents no longer here but always here

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Slim Laws for archiving the columns; Awa Press for the idea for this book; The Dominion Post and The Press for allowing it to happen; Pauline ORegan for the wonderful foreword; the backyard gang and the garage people for the camaraderie; Benecio for getting me through; and most of all the people of Christchurch, who keep on putting one foot in front of the other.

Jane Bowron

Foreword

As I read these daily accounts of life in Christchurch during and after the February earthquake, I found myself going through waves of unexpected emotion. As they say in the best psychological terms, they triggered emotions in me that I had scarcely known were there. After all, I live in Christchurch and I had also survived the quake quite well, I was inclined to think so I should have known what to expect. We all like to imagine we are in touch with our inner feelings, so my too-ready tears and bursts of slightly hysterical laughter seemed to call for an explanation. I had to ask what there was about Jane Bowrons writing that had affected me so deeply.

In the end I decided it was the immediacy of these accounts, the integrity, the honesty, the hitting-the-nail-on-the-head quality of them that had got to me. I feel sure that as Jane met the unforgiving deadline of a daily newspaper, she must have written these pieces at night, exactly as they had happened that same day. She tells us she is an insomniac and so I picture her sitting up in bed, writing, body on full alert for the next heart-racing aftershock, recalling the extraordinary events of the day just gone and recording them just as they happened, with no time for rueful adjustment or careful rewriting. You dont get writing more immediate than that and this writing is immediate and compelling.

I cant help feeling this is the way Samuel Pepys wrote his diary: late at night, desperate to get everything down within the limitations of a single page, telling it exactly as he experienced it that very day, urgently, immediately, honestly. That is surely the kind of pressure under which he recorded the terrible events surrounding the Great Fire of London in 1666 that destroyed his beloved city. Like Jane Bowrons earthquake of 2011, the fire was too terrible an event in itself to allow for any embellishment in the writing, too life-threatening to tolerate histrionics, too innately dramatic to need dramatic prose. So what we got from Pepys was a true, unadorned account of a great event in history, couched in good plain English. Jane Bowron has done no less.

I like to think that in these accounts of a great and terrible event in her lifetime, Jane has done for Christchurch what Samuel Pepys did for London. Both cities were destroyed by forces beyond human control, both writers were living in the heart of the city at the time, both loved their city dearly, and both conveyed without self-pity or excess of words that their hearts were broken.

I dont know what it has cost Jane in emotional and physical burn-out to write these accounts of the Christchurch earthquake, but I want her to know that she has done all of us a huge service. I experienced the quake and its aftermath in a city suburb. What I have lived through may not have all the intensity of her experience, living as she did in the inner city, within the cordon, but it has taken me to the limit of my endurance all the same. In this book, Jane has told my story and I am very grateful to her. I believe she has told the story of everyone in Christchurch who has experienced these events. And what is really heart-warming is that these stories were published first in a Wellington newspaper, and were received and valued by its readers, who were obviously interested in what we in Christchurch were going through and were concerned for our welfare. We needed that demonstration of solidarity and we drew courage from it.

Most of all, I believe this book will be important to generations to come. It will still be on bookshelves far into this century and grandparents will take it down and say to the children of the future: There was a terrible earthquake in Christchurch on February 22, 2011 and this is what happened

Pauline ORegan

August 2011

Riding the cycle of life and death

FEBRUARY 24 When the big aftershock of last years earthquake struck on Boxing Day, a friend texted, So God isnt happy with his presents then? After this Tuesdays earthquake it seems He doesnt like his churches very much either.

When the quake struck I was sitting in a caf, one of a group of alternative shops on the corner of Barbadoes and Kilmore Streets. People know the corner because of the Piko Wholefoods building, which is made of brick. Everyone marvelled when that building withstood the September quake, but on Tuesday at lunchtime it fell to become, like so many other broken buildings, a symbol of the architecture of suffering.

The caf next door, where I was, is made of iron, so when the quake hit I, like the rest of the occupants, tried to get out of my chair and move to the door. A young mother pushed, nearly threw, a baby into my arms so she could walk across the road to her car to get her cellphone. I stood in the middle of the road with this tiny baby as the building opposite fell to the ground and the owner miraculously sidestepped out of it.

All around, buildings started to deconstruct themselves into dolls houses with their sides off. In a matter of seconds the alternative shops of the Avon Loop had been wiped out, closed for business. People wept, embraced. I remember I kept saying, Were alive, were alive as we all came to the unspoken collective conclusion that this quake had been sent to cure us of any amnesia about last years September 4 quake and its horrid intent.

My flat was four doors away. After the mother was reunited with her baby I stumbled home to see that the two chimneys, which had been examined by the Earthquake Commission and approved three weeks previously, had taken aim and collapsed on my new Suzuki. Its not so swift now. Inside the flat there was the usual fury of thrown objects, everything smashed and covered with an unguent of oil, coated with flour.

Miriam, my neighbour, arrived and we packed backpacks full of towels and bandages, pills and any first aid we could find and walked intuitively to Latimer Square, an al fresco assembly point. At the far end, off-duty nurses were swiftly and efficiently tending to the injured while helicopters dropped first-aid kits. We left our contributions, assessing we would be more hindrance than help, and tried to comfort the elderly and bewildered.

Beyond Latimer Square, Madras Street was a mess of smoke, collapsed buildings, fire and panic. Yellow-jacketed emergency workers stood in a frozen tableau outside the CTV building like something seen on 9/11 footage. I had to check out Holy Trinity, the church where my brother is vicar, a historic church that is the oldest in Christchurch. When we came to the intersection of Kilmore Street and Fitzgerald Avenue the road became increasingly buckled. The bridge across the Avon looked precarious to say the least, and the traffic was gridlocked. Cars were packed with whatever the drivers could take to get out of Dodge as fast as possible. Other people were trying to leave their houses and join the line.

Next page