We hope you enjoyed reading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

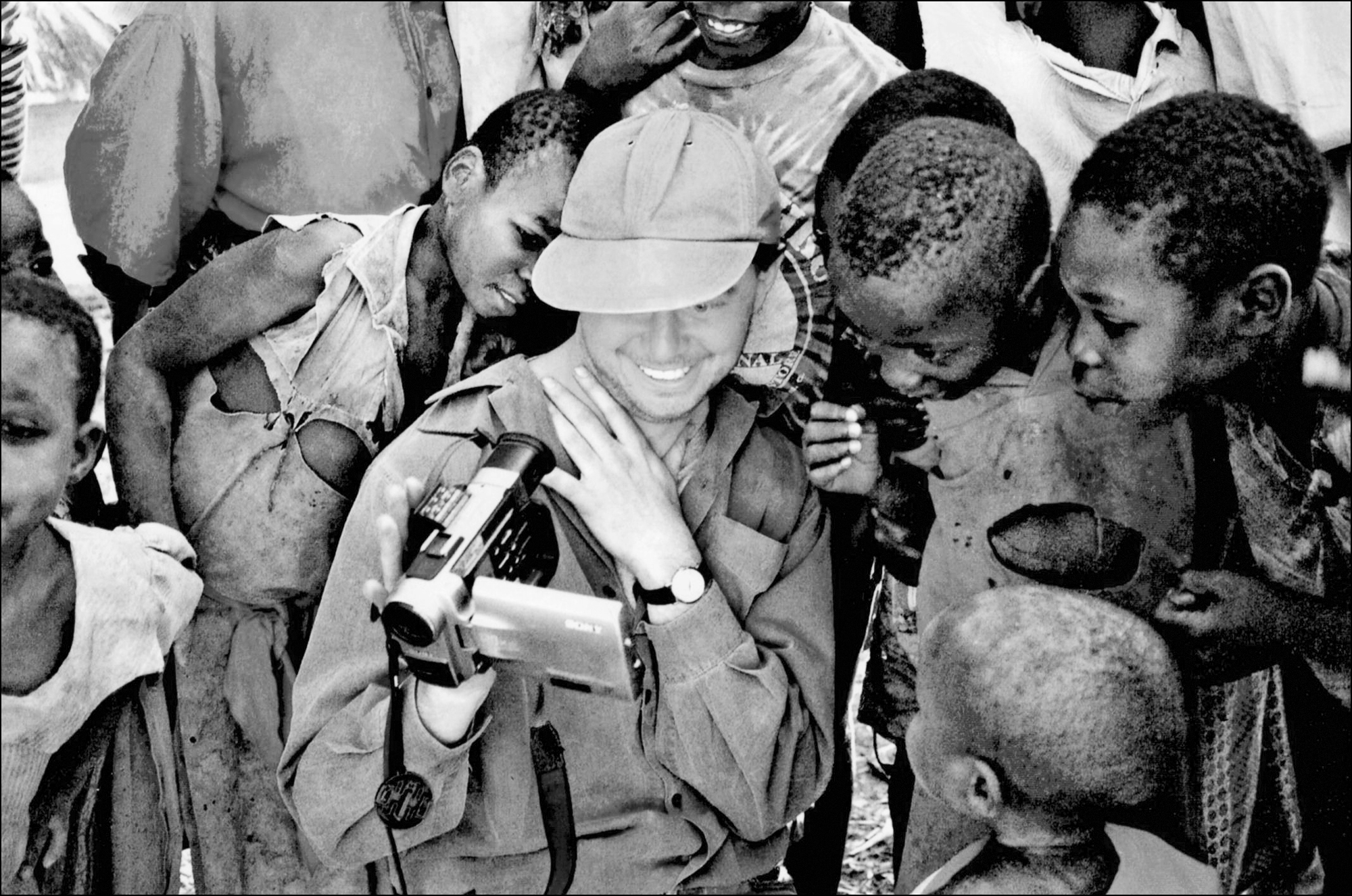

Zambia, 1997 (Photograph by Luca Trovato)

SCRIBNER

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

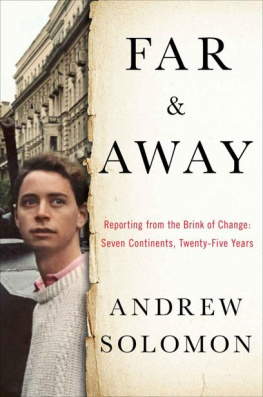

Copyright 2016 by Andrew Solomon

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition April 2016

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Andrew Solomon is represented as a speaker by the Tuesday Agency. For more information or to book an event, contact the agency at 1-319-338-7080. Further information may be found on Andrew Solomons website at www.andrewsolomon.com.

Interior design by Kyle Kabel

Jacket Design by Pete Garceau and Jaya Miceli

Jacket Photographs: Front by David Solomon, Spine by Gh. Farouq Samim

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4767-9504-1

ISBN 978-1-4767-9506-5 (ebook)

for Oliver, Lucy, Blaine, and George, who have given me a reason to stay home

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

...

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there... No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?

Elizabeth Bishop, Questions of Travel

Contents

Dispatches from Everywhere

W hen I was about seven, my father told me about the Holocaust. We were in the yellow Buick on New York State route 9A, and I had been asking him whether Pleasantville was actually pleasant. I cannot remember why the Nazis came up a mile or two later, but I do remember that he thought I already knew about the Final Solution, and so didnt have any rehearsed way to present the camps. He said that this had happened to people because they were Jewish. I knew that we were Jewish, and I gathered that if wed been there at the time, it would have happened to us, too. I insisted that my father explain it at least four times, because I kept thinking I must be missing some piece of the story that would make it make sense. He finally told me, with an emphasis that nearly ended the conversation, that it was pure evil. But I had one more question: Why didnt those Jews just leave when things got bad?

They had nowhere to go, he said.

At that instant, I decided that I would always have somewhere to go. I would not be helpless, dependent, or credulous; I would never suppose that just because things had always been fine, they would continue to be fine. My notion of absolute safety at home crumbled then and there. I would leave before the walls closed around the ghetto, before the train tracks were completed, before the borders were sealed. If genocide ever threatened midtown Manhattan, I would be all set to gather up my passport and head for some place where theyd be glad to have me. My father had said that some Jews were helped by non-Jewish friends, and I concluded that I would always have friends who were different from me, the kind who could take me in or get me out. That first talk with my father was mostly about horror, of course, but it was also in this regard a conversation about love, and over time, I came to understand that you could save yourself by broad affections. People had died because their paradigms were too local. I was not going to have that problem.

A few months later, when I was at a shoe store with my mother, the salesman commented that I had flat feet and ventured that I would have back problems in later life (true, alas), but also that I might be disqualified from the draft. The Vietnam War was dominating the headlines, and I had taken on board the idea that when I finished high school, Id have to go fight. I wasnt good even at scuffles in the sandbox, and the idea of being dropped into a jungle with a gun petrified me. My mother considered the Vietnam War a waste of young lives. World War II, on the other hand, had been worth fighting, and every good American boy had done his part, flat feet or otherwise. I wanted to understand the comparative standard whereby some wars were so righteous that my own mother thought they warranted my facing death, while others were somehow none of our business. Wars didnt happen in America, but America could send you off to war anyplace else in the world, rightly or wrongly. Flat feet or not, I wanted to know those places, so I could make my own decisions about them.

I was afraid of the world. Even if I was spared the draft and fascism failed to establish a foothold in the Nixon years, a nuclear attack was always possible. I had nightmares about the Soviets detonating a bomb in Manhattan. Although not yet acquainted with the legend of the Wandering Jew, I made constant escape plans and imagined a life going from port to port. I thought I might be kidnapped; when my parents were being particularly annoying, I imagined I had already been kidnapped, taken away from nicer people in some more benign country to be consigned to this nest of American madness. I was precociously laying the groundwork for an anxiety disorder in early adulthood.

Running in counterpoint to my reckonings with destruction was my growing affection for England, a place I had never visited. My Anglophilia set in about the time my father started reading me Winnie-the-Pooh when I was two. Later, it was Alice in Wonderland , then The Five Children and It , then The Chronicles of Narnia. For me, the magic in these stories had to do as much with England as with the authors flights of fancy. I developed a strong taste for marmalade and for the longer sweep of history. In response to my various self-indulgences, my parents usual reprimand was to remind me that I was not the Prince of Wales. I conceived the vague idea that if I could only get to the UK, I would receive entitlements (someone to pick up my toys, the most expensive item on the menu) that I associated more with location than with an accident of birth. Like all fantasies of escape, this one pertained not only to the destination, but also to what was left behind. I was a pre-gay kid who had not yet reckoned with the nature of my difference and therefore didnt have a vocabulary with which to parse it. I felt foreign even at home; though I couldnt yet have formulated the idea, I understood that going where I would actually be foreign might distract people from the more intimate nature of my otherness.