Table of Contents

For Mary

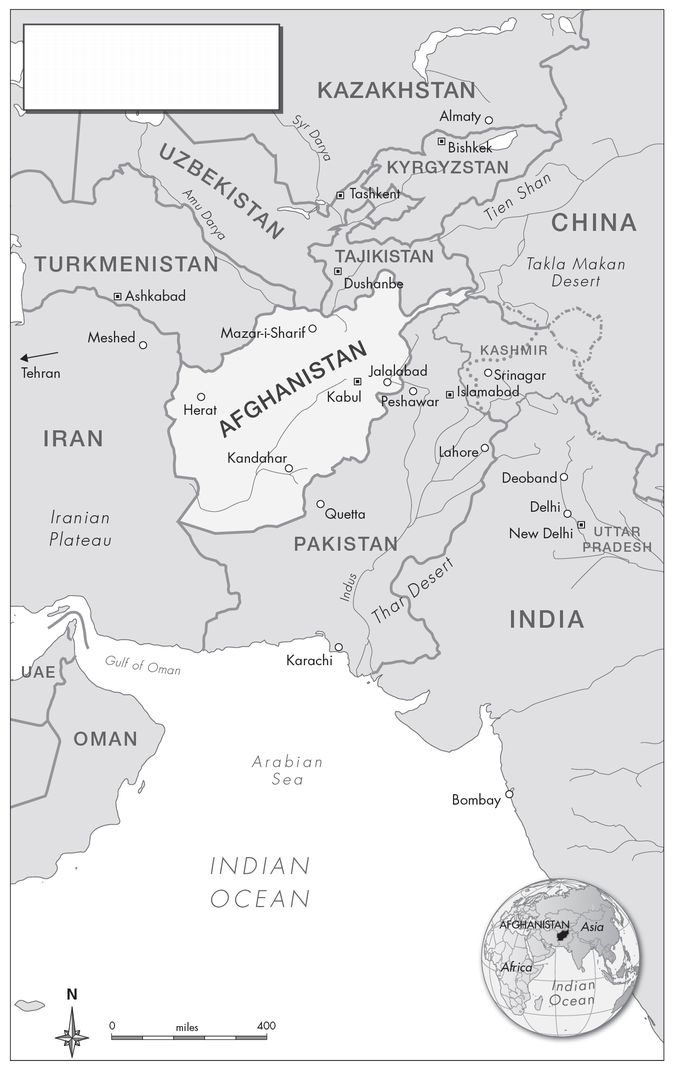

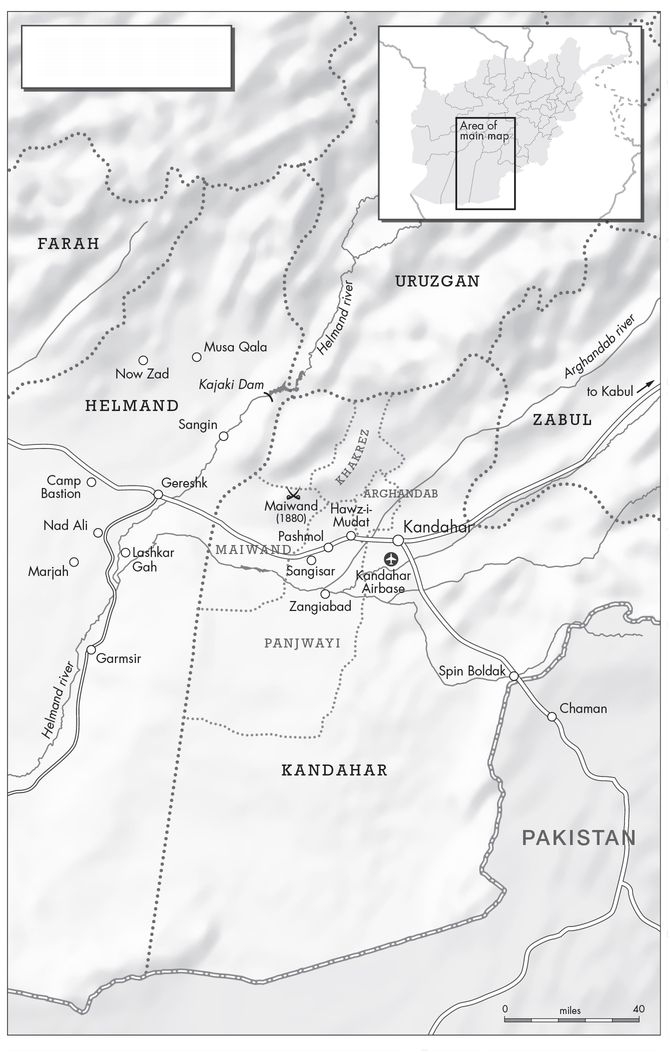

AFGANISTAN & REGION

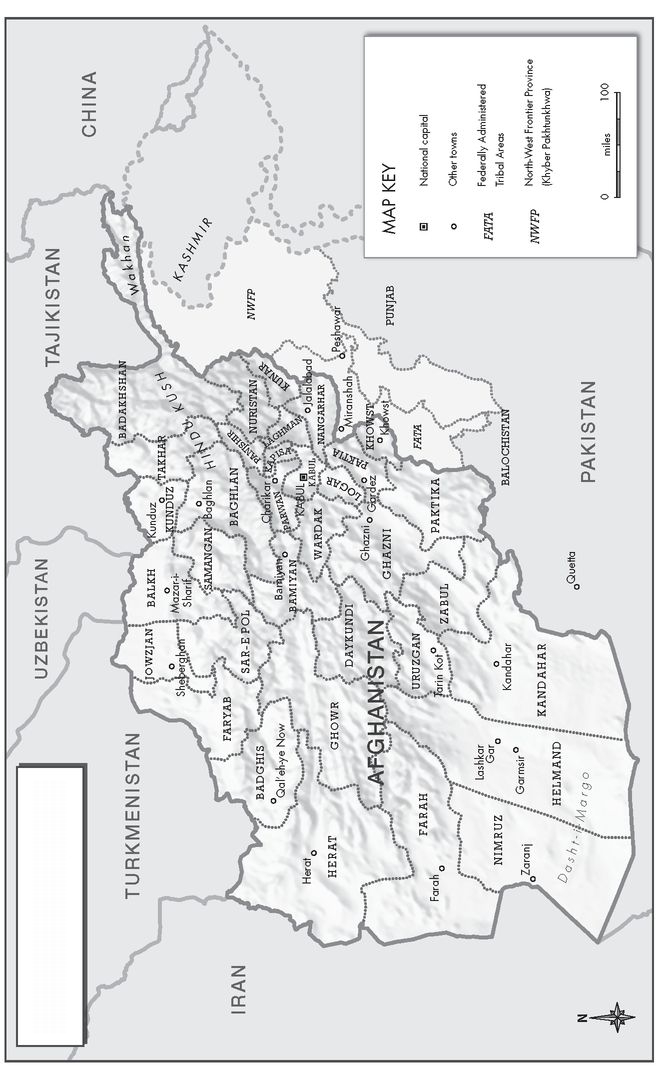

AFGHANISTAN

KANDAHAR

Introduction

In a previous book, A Million Bullets, an account of the British Armys battle with the Taliban in Helmand in 2006, I argued in its conclusion that negotiation with the enemy might be a better alternative to fighting them. Ever since at conferences and literary festivals, in the comment pages of Sunday newspapers, on national radio and television, in private meetings with senior politicians and soldiers, even in testimony to a House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee I have repeated the axiom that no counter-insurgency in history has concluded without dialogue with the enemy. No one ever contested the assertion. And yet, nine miserable years after the campaign against the Taliban began, there has been no contact between the West or any of its allies and the insurgencys undisputed leader, Mullah Omar: not so much as a text message.

This book is written from a deep conviction that we must change tack. The insurgency is still expanding and Afghans have lost confidence in our ability to stem it, as well as in our ability to establish an alternative government in Kabul that is truly worthy of their support. A negotiated settlement with the Taliban looks increasingly like the Wests only way out of the mess.

Our strategy to date has been dominated by military rather than civilian thinking, and it is failing in large part because we continue to misunderstand the nature of the opposition.

There are those who are propagating war based on an extreme, perverted view of Islam. Those people are not reconcilable, the former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown once remarked. Yet if the problem is the perversion of Islam a characterization of their religion, incidentally, that a great many Afghans, not just the Taliban, would dispute is reconciliation not more likely to be achieved through theological debate rather than military force? The Taliban are the representatives of an ideology as much as they are an army. It follows that we need to win arguments with them, not just battles and we cant do that without talking to them. How much, in the end, do we really know about the Taliban and their motives? Not nearly enough, I would suggest. And yet according to Sun Tzus The Art of War, the famous ancient Chinese text still taught in Nato staff colleges, know your enemy is one of the first precepts of successful warfare.

In the first part of this book I have traced the origins and history of Mullah Omars extraordinary movement from 1994 to the present day, with the aim of demonstrating that the Taliban were never quite the bearded bigots of popular Western imagination. The second part is dedicated to conversations with leading members of the so-called reconciled Taliban, who are likely to emerge as key mediators in any peace deal with Omar in the future, and tackles these more immediate questions: what might such a deal look like? What would it mean for Afghanistan and the world, and how can it be achieved?

A compromise would not necessarily entail the abandonment of the Wests principal goal.

Let us not forget why we are in Afghanistan, the US General David Petraeus said in November 2009. It is to ensure that this country cannot become once again a sanctuary for al-Qaida.

Forget, for a moment, democratization, development, reform. They are all optional extras: desirable in themselves, perhaps, but nevertheless means to a greater end. Omar wants the withdrawal of foreign troops and the establishment of Sharia law in his country. In return for a guarantee to keep al-Qaida out of Afghanistan, is it unthinkable now to grant him this wish? Our policy-makers assume that Omar could never be trusted to keep al-Qaida out, but how can they be sure when they have never asked him?

Western troop withdrawal, phased and carefully timetabled, would not mean the abandonment of Afghanistan. On the contrary, the departure of our soldiers should be coordinated with a massive uplift in aid, paid for by savings from the military effort: the civilian-led development programme that we should perhaps have concentrated on in the first place. In February 2010, for the first time, the Pentagon spent more in a month on Afghanistan than it did on Iraq: $6.7 billion compared to $5.5 billion, or $233 million a day. This is about three times what the Taliban government, before it was ousted, could afford to spend on civil development in an entire year. How many roads or schools or hospitals could be built with a budget as big as that? Such reconstruction could only happen with the consent of the Taliban, of course; but there is every reason to think that they would give their consent. They did in the past. The Taliban are not against Western aid and development in principle. It is the presence of infidel troops they primarily object to, and when they destroy a newly built school or well or road, it is often because they see these projects perhaps with some reason as weapons in a Western counter-insurgency campaign.

As an organization they have been relentlessly demonized: a byword for extremism, the most infamous religious movement of our times. They were doubtless guilty of many excesses when they were in power. Crucial questions remain about how they would treat the non-Pashtun minority should they return to the political mainstream particularly the Hazara Shiites, the victims of serious persecution in the late 1990s. The footage of public executions carried out in a Kabul football stadium remains hard to comprehend in the West. We are rightly outraged by those insurgents who apparently see nothing wrong in using women and children as human shields on the southern battlefields of today.

Yet the truth is that the Taliban were never as uniformly wicked as they were routinely made out to be and nor are they now. The original idea behind their movement was not evil, but noble. Perhaps like all popular revolutions, theirs took off in directions unanticipated by its founders, and much of the idealism that underpinned it became lost. But not, they insist, irrevocably so; and if they are convinced they could do better next time, who are we to say that they are wrong?

More to the point, the Afghans themselves now seem ready to offer the Taliban a second chance: even some Afghan women.

I changed my view three years ago when I realized Afghanistan is on its own, said Shukria Barakzai, an MP and one of the countrys leading womens rights campaigners. Its not that the international community doesnt support us. They just dont understand us. The Taliban are part of our population. They have different ideas, but as democrats we have to accept that.

In 1999, Barakzai was beaten by the Talibans religious police in Kabul when she went to the doctors unaccompanied by her husband. If even she is prepared to consider a compromise with her former tormentors, should not the West be listening?