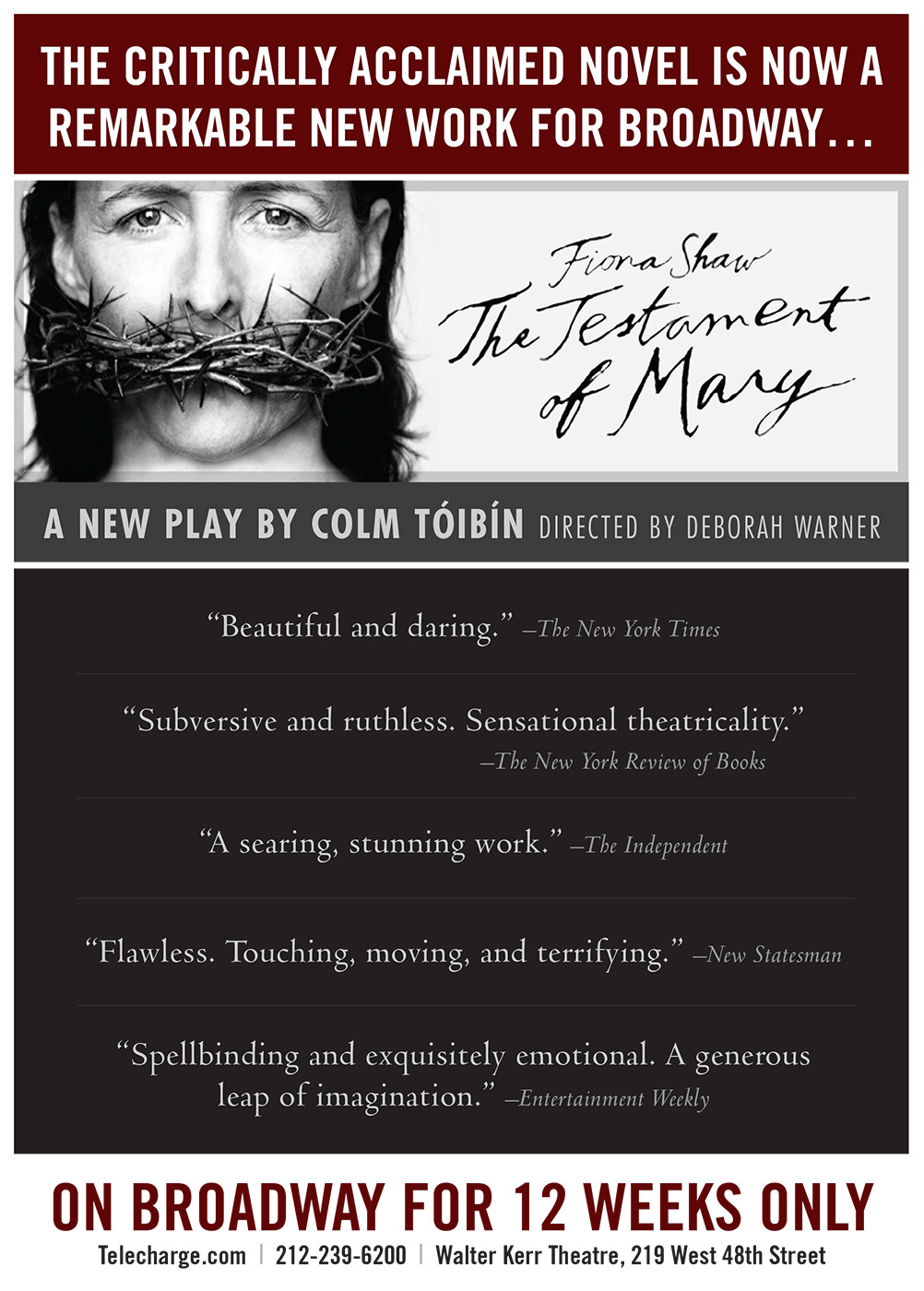

VISIT TESTAMENTONBROADWAY.COM/SCRIBNER

FOR AN EXCLUSIVE OFFER AND THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS

ALSO BY COLM TIBN

FICTION

The South

The Heather Blazing

The Story of the Night

The Blackwater Lightship

The Master

Mothers and Sons

Brooklyn

The Empty Family: Stories

NONFICTION

Bad Blood: A Walk Along the Irish Border

Homage to Barcelona

The Sign of the Cross: Travels in Catholic Europe

Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives from Wilde to Almodvar

Lady Gregorys Toothbrush

New Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and Their Families

PLAYS

Beauty in a Broken Place

Testament

Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

For Loughlin Deegan and Denis Looby

The Testament of Mary

T hey appear more often now, both of them, and on every visit they seem more impatient with me and with the world. There is something hungry and rough in them, a brutality boiling in their blood, which I have seen before and can smell as an animal that is being hunted can smell. But I am not being hunted now. Not anymore. I am being cared for, and questioned softly, and watched. They think that I do not know the elaborate nature of their desires. But nothing escapes me now except sleep. Sleep escapes me. Maybe I am too old to sleep. Or there is nothing further to be gained from sleep. Maybe I do not need to dream, or need to rest. Maybe my eyes know that soon they will be closed for ever. I will stay awake if I have to. I will come down these stairs as the dawn breaks, as the dawn insinuates its rays of light into this room. I have my own reasons to watch and wait. Before the final rest comes this long awakening. And it is enough for me to know that it will end.

They think I do not understand what is slowly growing in the world; they think I do not see the point of their questions and do not notice the cruel shadow of exasperation that comes hooded in their faces or hidden in their voices when I say something vague or foolish, something which leads us nowhere. When I seem not to remember what they think I must remember. They are too locked into their vast and insatiable needs and too dulled by the remnants of a terror we all felt then to have noticed that I remember everything. Memory fills my body as much as blood and bones.

I like it that they feed me and pay for my clothes and protect me. And in return I will do for them what I can, but no more than that. Just as I cannot breathe the breath of another or help the heart of someone else to beat or their bones not to weaken or their flesh not to shrivel, I cannot say more than I can say. And I know how deeply this disturbs them and it would make me smile, this earnest need for foolish anecdotes or sharp, simple patterns in the story of what happened to us all, except that I have forgotten how to smile. I have no further need for smiling. Just as I had no further need for tears. There was a time when I thought that I had, in fact, no tears left, that I had used up my store of tears, but I am lucky that foolish thoughts like this never linger, are quickly replaced by what is true. There are always tears if you need them enough. It is the body that makes tears. I no longer need tears and that should be a relief, but I do not seek relief, merely solitude and some grim satisfaction which comes from the certainty that I will not say anything that is not true.

Of the two men who come, one was there with us until the end. There were moments then when he was soft, ready to hold me and comfort me as he is ready now to scowl impatiently when the story I tell him does not stretch to whatever limits he has ordained. Yet I can see signs of that softness still and there are times when the glow in his eyes returns before he sighs and goes back to his work, writing out the letters one by one that make words he knows I cannot read, which recount what happened on the hill and the days before and the days that followed. I have asked him to read the words aloud to me but he will not. I know that he has written of things that neither he saw nor I saw. I know that he has also given shape to what I lived through and he witnessed, and that he has made sure that these words will matter, that they will be listened to.

I remember too much; I am like the air on a calm day as it holds itself still, letting nothing escape. As the world holds its breath, I keep memory in.

So when I told him about the rabbits I was not telling him something that I had half forgotten and merely remembered because of his insistent presence. The details of what I told him were with me all the years in the same way as my hands or my arms were with me. On that day, the day he wanted details of, the day he wanted me to go over and over for him, in the middle of everything that was confused, in the middle of all the terror and shrieking and the crying out, a man came close to me who had a cage with a huge angry bird trapped in it, the bird all sharp beak and indignant gaze; the wings could not stretch to their full width and this confinement seemed to make the bird frustrated and angry. It should have been flying, hunting, swooping on its prey.

The man also carried a bag, which I gradually learned was almost half full of live rabbits, little bundles of fierce and terrorized energy. And during those hours on that hill, during the hours that went more slowly than any other hours, he plucked the rabbits one by one from the sack and edged them into the barely opened cage. The bird went for some part of their soft underbelly first, opening the rabbit up until its guts spilled out, and then of course its eyes. It is easy to talk about this now because it was a mild distraction from what was really going on, and it is easy to talk about it too because it made no sense. The bird did not seem to be hungry, although perhaps it suffered from a deep hunger that even the live flesh of writhing rabbits could not satisfy. The cage became half full of half-dead, wholly uneaten rabbits exuding strange squealing sounds. Twitching with old bursts of life. And the mans face was all bright with energy, there was a glow from him, as he looked at the cage and then at the scene around him, almost smiling with dark delight, the sack not yet empty.

By that time we had spoken of other things, including the men who played with dice close to where the crosses were; they played for his clothes and other possessions, or for no special reason. One of these men I feared as much as the strangler who arrived later. This first man was the one among all those who came and went during the day who was most alert to me, most menacing, the one who seemed most likely to want to know where I would go when it was over, the one most likely to be sent to bring me back. This man who followed me with his eyes seemed to work for the group of men with horses, who sometimes appeared to be watching from the side. If anyone knows what happened that day and why, then it is this man who played with dice. It might be easier if I said that he comes in dreams but he does not, nor does he haunt me as other things, or other faces, haunt me. He was there, that is all I have to say about him, and he watched me and he knew me, and if now, after all these years, he were to arrive at this door with his eyes narrowed against the light and his sandy-coloured hair gone grey and his hands still too big for his body, and his air of knowledge and self-possession and calm, controlling cruelty, and with the strangler grinning viciously behind him, I would not be surprised. But I would not last long in their company. Just as my two friends who visit are looking for my voice, my witness, this man who played dice, and the strangler, or others like them, must be looking for my silence. I will know them if they come and it should hardly matter now, since the days left are few, but I remain, in my waking time, desperately afraid of them.

Next page