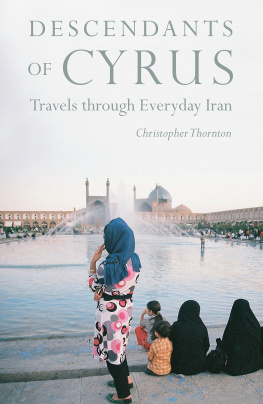

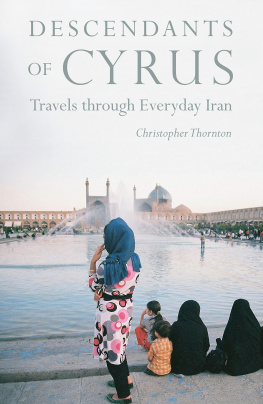

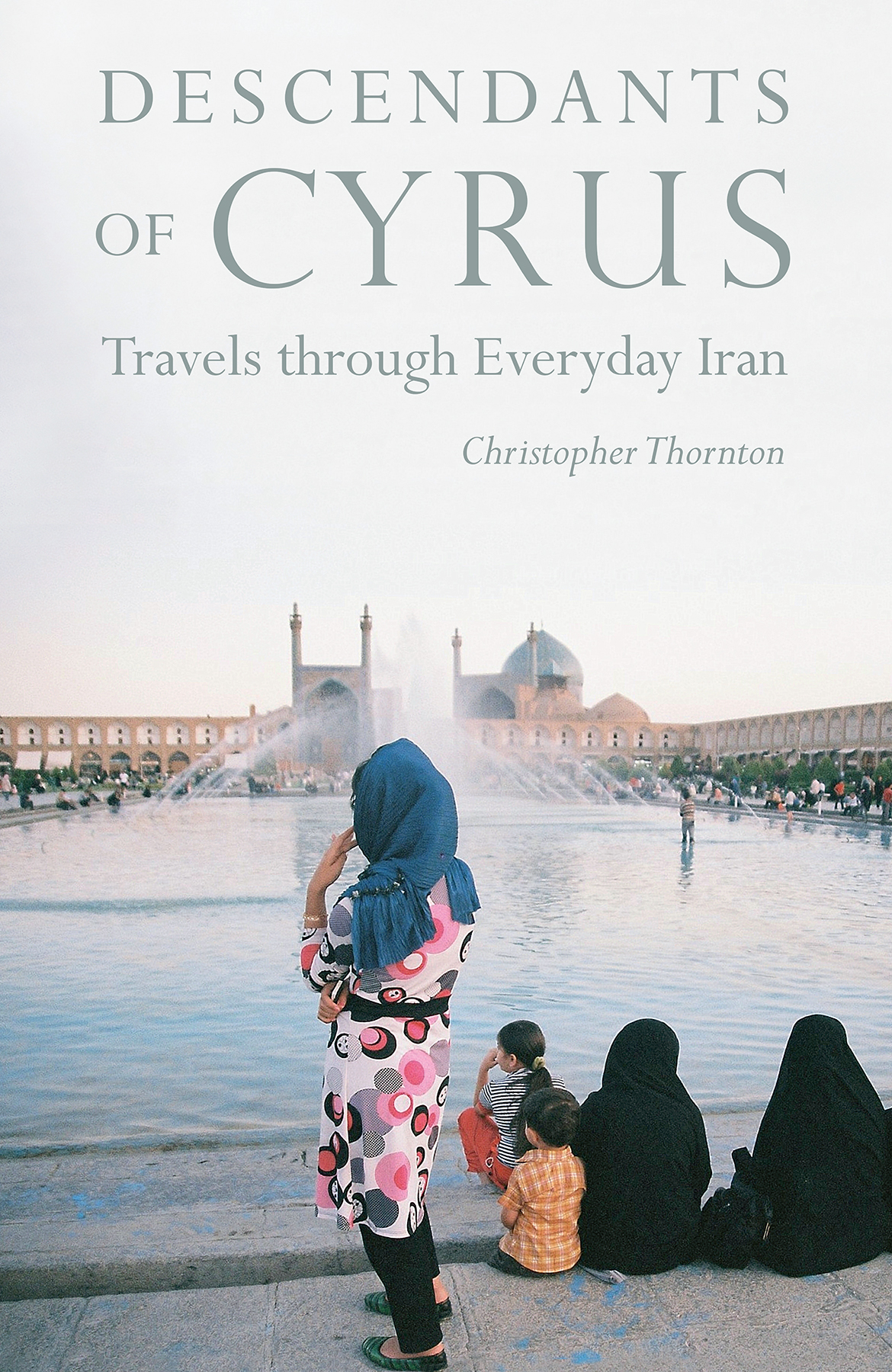

Descendants of Cyrus

Travels through Everyday Iran

Christopher Thornton

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2019 by Christopher Thornton.

Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

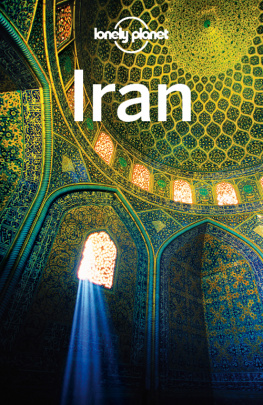

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Christopher Thornton.

All other photos courtesy of the author.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thornton, Christopher, author.

Title: Descendants of Cyrus: travels through everyday Iran / Christopher Thornton.

Description: Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press [2019].

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009201

ISBN 9781640120372 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781640122703 (epub)

ISBN 9781640122710 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640122727 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : IranDescription and travel. | Thornton, ChristopherTravelIran.

Classification: LCC DS 259.2 . T 48 2019 | DDC 955dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009201

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

I am an Iranian. A descendant of Cyrus the Great. The very emperor who proclaimed at the pinnacle of power 2,500 years ago that he would not reign over the people if they did not wish it. And [he] promised not to force any person to change his religion and faith and guaranteed freedom for all.

Shirin Ebadi, Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, 2003

Contents

First of all, Id like to express great appreciation to all of my Iranian friends for the enthusiasm, support, and advice they offered from the start of this project. This also includes the people of Iran, whose warmth and hospitality I was so fortunate to receive on my three trips to the country, and all of whom I consider friends-at-large. They convinced me of the merits of this book and its messagethat there is another side of Iranian history, culture, and society that the world outside of Iran needs to be aware of, in order to bring greater understanding to the political differences of today. Then there is the editorial staff at Potomac BooksTom Swanson, Ann Baker, and the rest of the teamwho also recognized the merits of the book and had the necessary experience and professionalism to see it through to completion. This includes Virginia Perrin, the copy editor, who toiled over the manuscript with the meticulous care needed to catch slight inconsistencies in spellings and terminology that my glazed eyes could no longer identify. A very special thanks goes to my Iranian content editor, who supplied invaluable suggestions and corrections to the fine points of Persian history, culture, and language. Finally, let me not forget my agent, Erik Hane, the catalyst for this entire effort. Had he not recognized the value of the book and relentlessly gone about finding a publisher, none of the rest of us would have had much to do these past many months.

Editorial note: Transliterations from languages that dont use the Latin alphabet can often be messy, and Farsi, particularly, poses special challenges. With that in mind, every effort was made to settle on Latin spellings that most closely represent the original Farsi terms and pronunciations. If any of these cause an affront to Persian linguists, I can only express my sincerest regrets.

Tehran

Two Tales from One City

There is not a single school or town that is excluded from the happiness of the holy defense of the nation, from drinking the exquisite elixir of martyrdom, or from the sweet death of the martyr, who dies in order to live forever in paradise.

Etalaat newspaper, in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War

In a scene near the beginning of the film Argo, about the rescue of the U.S. diplomats held hostage at the beginning of the Islamic Revolution, there is a shot of the Tehran skyline with a backdrop of the snowcapped Alborz Mountains. It is reminiscent of similar shots of Boulder, Colorado, set against the panorama of the American Rockies. Like the Rockies, the Alborz are suffused with mythology, which would be expected of any natural feature in an ancient land. According to Indian philosophy, all of the continents were connected by a single mountain range. Ancient Persian thinkers took this a step further, believing that the Earths mountains rose from a round, flat plain, and beneath the surface they were linked together like plants joined at their roots, and this union formed a unifying force. Above ground the mountains were drawn together by a single peak. In the case of the Alborz this would be Mount Damavand, at 15,312 feet the highest in the Middle East. Some historians believe that this line of thinking paved the way for Zoroastrianism and the concept of monotheism.

The shot from Argo, and any of Tehran that feature the backdrop of the Alborz, as most do, is an apt metaphor of life in Iran today. One only needs to imagine the mountains as the Islamic regime: It is a looming fact of daily life, always present and never to be ignored. At times it may seem to disappear, just as the mountains are occasionally shrouded by the Tehran smog, but always it returns, as fixed and immobile as the mountains themselves.

The mountains have been a fixture of the landscape longer than the city they tower over. Tehran is not one of the great capitals of the Middle East, like Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad. As Middle Eastern cities go, Tehran is an upstart. Until the end of the first millennium the dominant city south of the Caspian Sea was Rey, or Raghes in its ancient form. But Rey was not meant to last. It was attacked, destroyed, and rebuilt after invasions by the Arabs in the seventh century and the Turks in the eleventh. In the thirteenth century the Mongols provided the death blow, razing the city and slaughtering most of the residents. Nearby Tehran, previously known only for agricultural production, primarily pomegranates, became a convenient alternative for urban settlement. It slowly grew into a small city, and by the sixteenth century it became an important administrative center of the Safavid dynasty. In 1796 Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar chose to make it his capital.

To say that Persian rulers have been fickle in their choice of capitals is an understatement. Tehran is the thirty-second in the history of the empire. Agha Mohammad Khans reasoning, like that of his predecessors, was strategic. Tehran was close to the Caucasus region, then under Persian rule but threatened by imperial Russia, and it was a safe distance from an aggressive Ottoman Empire to the northwest. Also, by choosing Tehran as his capital he stayed clear of the regional rivalries in Shiraz and Esfahan and local leaders who might rebel against him. Tehran was, in many ways, a safe pick.

In 1850 the city had only eighty thousand inhabitants, but in 1878 a new plan expanded the city walls, and in the 1920s and 1930s Reza Shah Pahlavi rebuilt the city in quasi-European style, cutting wide boulevards through dense neighborhoods and laying out streets in the grid pattern copied from the Europeans. New buildings combined Western and traditional Persian designs, as Iran began to look westward for cultural influence. The modernization trend accelerated under Pahlavis son, Mohammad Reza Shah, who aimed to tilt Iran further westward. New universities and research centers opened, again mimicking European architectural styles but with a hint of Persian classicism. Tehran became the capital of not only the Iranian government but a thriving cultural scene. The population swelled.

Next page