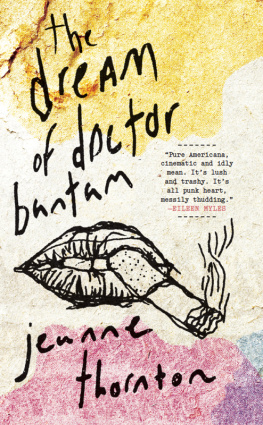

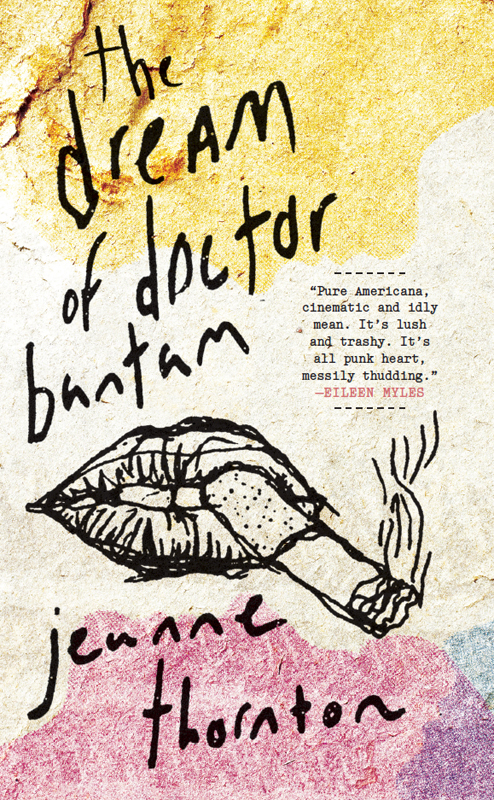

Illustrations and text 2012 Jeanne Thornton

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-935928-87-4 paperback

ISBN 978-1-935928-88-1 e-book

Typeset by Lapiz Digital, Chennai, India.

Printed by BookMobile in the United States and CPI Books Ltd in the United Kingdom. The U.S. printed edition of this book comes on Forest Stewardship Council-certified, 30% recycled paper. The printer, BookMobile, is 100% wind-powered.

TO THE GREAT XERXES

and to Steve Keller, Lisa McPherson,

Russell Miller, Andreas Heldal-Lund

When Tabitha Thatch argued, her little sister Julie always thought about cats. It was rare that Tabitha argued, much more common that she agreed to rules or demands her mother or the world imposed on her, then did the opposite of what shed agreed to, but when she did argue her jaw relaxed open and her voice, high-pitched and ragged, folded in on itself in a hundred tissue paper layers of connotation, implication, meaning, all of her yowling protest in way you couldnt ignore. You could listen to Tabitha arguing like a cat for hours; Julieher own voice like a dogs, she thought, short and hoarse and barky had listened to Tabitha for hours. You could listen and you would be struck by how raw and vibrant that voice was, but then youd realize that Tabitha was just saying she was going to go to the mall and buy Adderall, swallow it with beer, then hang around the food court talking about the Misfits with some college kid. In a raw and vibrant and catlike way shed tell you that and you would believe in her.

Linda, Tabitha and Julies mother, had never been vulnerable to Tabithas voice, and Julie had always hated Linda a little for that.

They were fighting now, Tabs and Linda; their voices came through the walls of Julies bedroom like foreign talk radio on the AM dial. Julie sat up on the edge of her bed, recently stripped of its alphabet-patterned case and replaced with a more grown-up deep green color that reminded her of rainforests; she felt her long hair sticking up in crazy roller-coaster loops at the back of her head. The air of the room was somehow just wrong; like Lucy in Voyage of the Dawn Treader , shed slipped into another dimension, one in which she wasnt able to get any sleep before her algebra test the next day, one in which the red digital clock was blinking midnight at her in some sick parody of good morning.

She went into the hallway, still in her white Apple Records T-shirt and boxers, sat on the floor outside Lindas bedroom, curled her legs up to her body, and listened to them.

Everything has to have a reeeason , thats your problem, Tabitha was saying. What if my reason is just that I want to spend all day lying in a field or something? And writing long letters to ex-boyfriends? What if thats my reason?

I dont give a shit what your reason is, Linda said. I dont care how boring or irrelevant you think your classes are, either. You think I dont spend eight or nine hours a day doing boring and irrelevant stuff?

I think youre spending right now doing boring and irrelevant stuff, said Tabitha. Now count toward that eight or nine hours?

Its called survival , said Linda. You do what you have to in order to survive. Its not called fun , or quit school so I can go out with boys and work at a fucking video arcade and smoke pot in the house all day . At least smoke in the garage.

Im an adult, mewled Tabitha. I can, you know, possibly make decisions without subjecting them to some neurotic process of analysis about, you know, what might possibly go wrong or

Youre seventeen, said Linda.

And the video arcade is a good job, said Tabitha, mother .

Linda laughed. Julie buried her cheeks deeper into her bare bony knees.

There are no good jobs, she said. Just lucrative jobs that you hate. Your job is neither lucrative, nor do you hate it.

Ill move out, said Tabitha. Ill move out, and maybe Julie will come with me, and you wont have us hanging around all the time making your life miserable.

Youre stoned, said Linda. Im not going to argue with you while youre stoned.

Ewwww , youre stoooooooooned , said Tabitha; she must have been pinching her nostrils shut.

Get out of my room! said Linda. Go to bed. And youre going back to that school in the morning, youre telling them that you changed your mind

Ewwww , get out of my rooooom , said Tabitha, and this time she giggled.

The TV came on immediately, some infomercial. There was a snort, then a stomp, and then Julies eyes were blinded by the lamplight. Tabitha stormed into the hallway and slammed the door behind her. She turned and her eyes fell to the ball of Julie at her feet. She stopped before her sister.

What the fuck are you doing in the hallway? she asked. Were you spying on us?

Yes, Julie said.

Tabitha stared down at her; Julie stared back up. When Tabitha got like this you couldnt be reasonable; you had to just match her, crazy for crazy. Even in the dark hallway Julie thought her older sister was beautiful: her hair, hay-blonde like Julies, bleached and highlighted in pink like celery stalks in red water. Her skirt torn, her stockings striped, her shirt full of rhinestones like the constellations Julie liked to memorize from books and try to see through the fluorescent haze of Austin streetlights. The rhinestones spelled out NO FUTURE. Tabitha put her hands on her hips and pursed her mouth. Her lips were painted in red and outlined in black. The epaulets of her leather jacket rose and fell as she breathed.

Come on, Tabitha said. Lets get out of here.

Where are we going? Julie asked.

Anywhere but here, said Tabitha. I dont know. Well get pancakes. Come on.

Julie got up; the shoulders of her T-shirt were nearly even with Tabithas epaulets. Somehow, at thirteen, shed become as tall as her sister when she wasnt paying attention.

Let me go get dressed, she asked.

Youll take forever, said Tabitha. Come on, trust me; lets just go. Its the millennium.

Julies flip-flops were stacked under the coat rack by the door; she put them on and followed Tabitha out into the front yard, crossed the lawn in her Apple Records T-shirt and boxers. Her legs shivered in the spring night and every window in every neighbors house could have been an eyeball. She got into the car next to her sister. Tabitha lit a cigarette, a tulip of fire surrounded by the black petals of her painted nails. Against the light her eyes were red at the edges. She turned the key.

They didnt talk as they drove down 2222 and merged onto the highway bearing south. One of Tabithas Smashing Pumpkins CDs was blaring quietly.

Next page