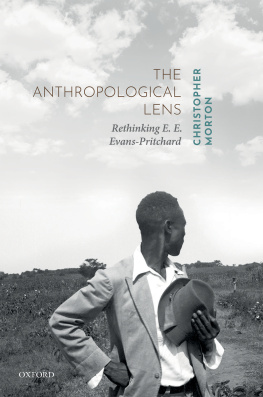

The Anthropological Lens

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Christopher Morton 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947000

ISBN 9780198812913

ebook ISBN 9780192542267

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgements

When I began research on E. E. Evans-Pritchard in 2003 as part of an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project on the Pitt Rivers Museums South Sudan collections, I little imagined that I would write a book such as this. I owe its existence to the two colleagues who spearheaded that project, Jeremy Coote and Elizabeth Edwards, whose encouragement and support I will always be deeply grateful for. The research formed the basis of a subsequent postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Oxford funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England, during which time some of the ideas I explore in this book were first published. A section of is based on another article published in Visual Anthropologyin 2009. All of the photographs reproduced are from the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, unless otherwise stated, and I am grateful to the museum for permission to reproduce them.

After a detour to work on other topics, this book began to take shape during a Leverhulme Fellowship in 2016, and I am very grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for their essential support. I am indebted to many friends and colleagues in Oxford and elsewhere for their help, encouragement, as well as critical feedback over the years, that have shaped the work in many ways, including Perez Achieng, Ahmed Al-Shahi, Angelo Beda, Dominic Byatt, Zoe Cormack, John Evans-Pritchard, Philip Grover, Wendy James, Jok Madut Jok, Douglas Johnson, Patti Langton, Alexander Maitland for permission to reproduce the contents of letters to Sir Wilfred Thesiger, Mike OHanlon, Gilbert Oteyo, Katherine Rose, Bruce Ross-Smith, David Shankland, Andr Singer, Richard Vokes. This book is for Catherine, Blake, and Conrad.

Table of contents

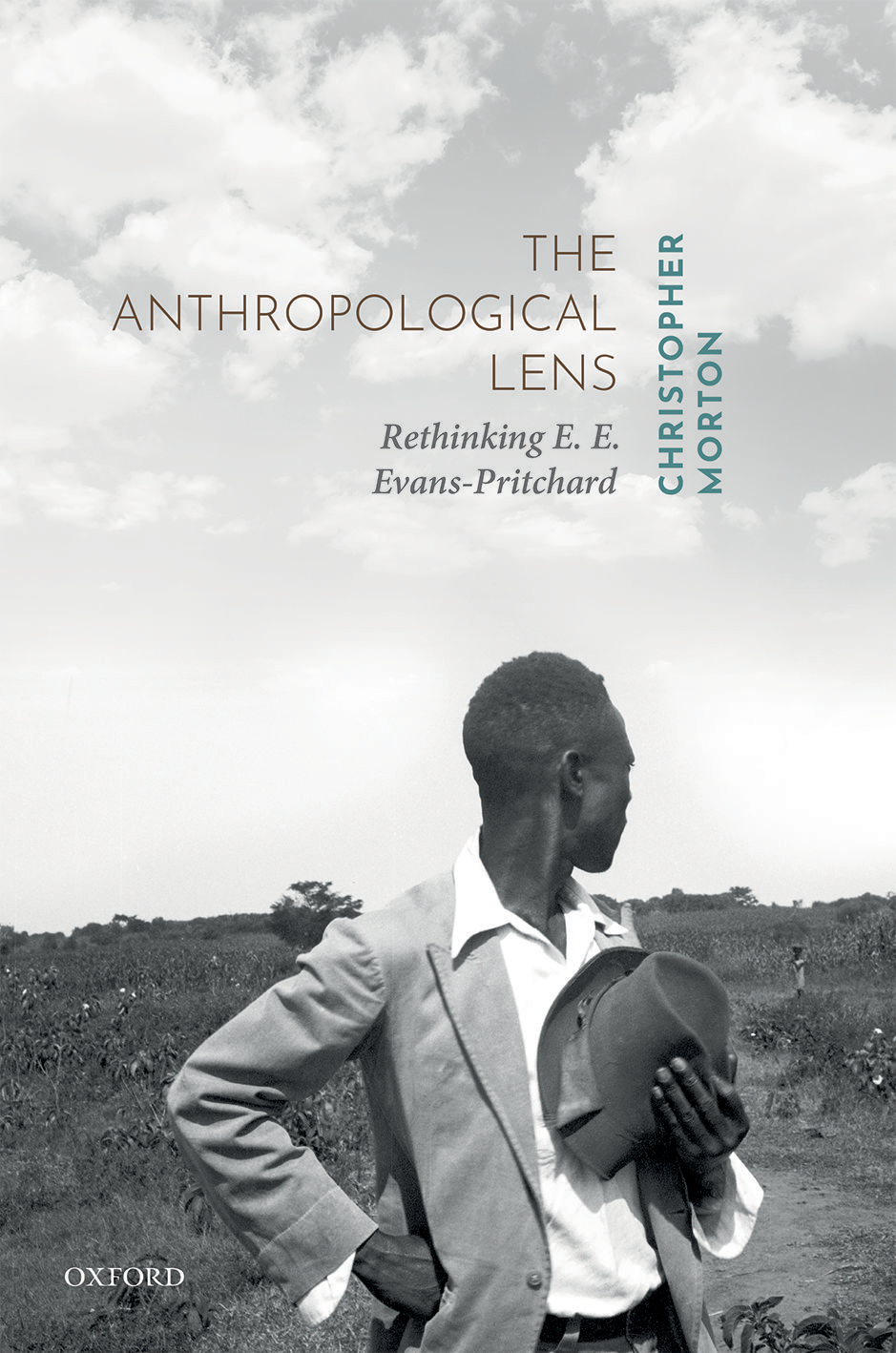

Cover:

Attempted portrait of a Luo man, Gangu village, Alego location, Nyanza, Kenya. Photograph by E. E. Evans-Pritchard, 1936. Copyright Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (1998.349.245.1).

This book is a new perspective on probably the most important British anthropologist of the twentieth century; new because I take his photography as a starting point to rethink the way in which his fieldwork experiences and encounters shaped his work. I examine his photographs, but say little about him as a photographer; I discuss his collection of vernacular texts and other archival evidence, but I leave the comprehensive search for correspondence and other evidence of his personal thoughts and life to future biographers. The photographs allow us a new route into understanding the way in which Evans-Pritchards fieldwork shaped his theoretical contributions, offering us an alternative analysis of the generation of anthropological knowledge and theory. Yet this is not a book that seeks to rediscover Evans-Pritchard as an overlooked photographer who deserves recognition as an artist of the mediumhe wasnt. Whereas other significant anthropological figures of the twentieth centurysuch as Bronislaw Malinowski and Isaac Schaperahave both had their field photographs published in volumes with commentaries in recent years, I have not set out to add Evans-Pritchard to this canon, whose future membership the historian Elizabeth Edwards awaited with rueful curiosity.