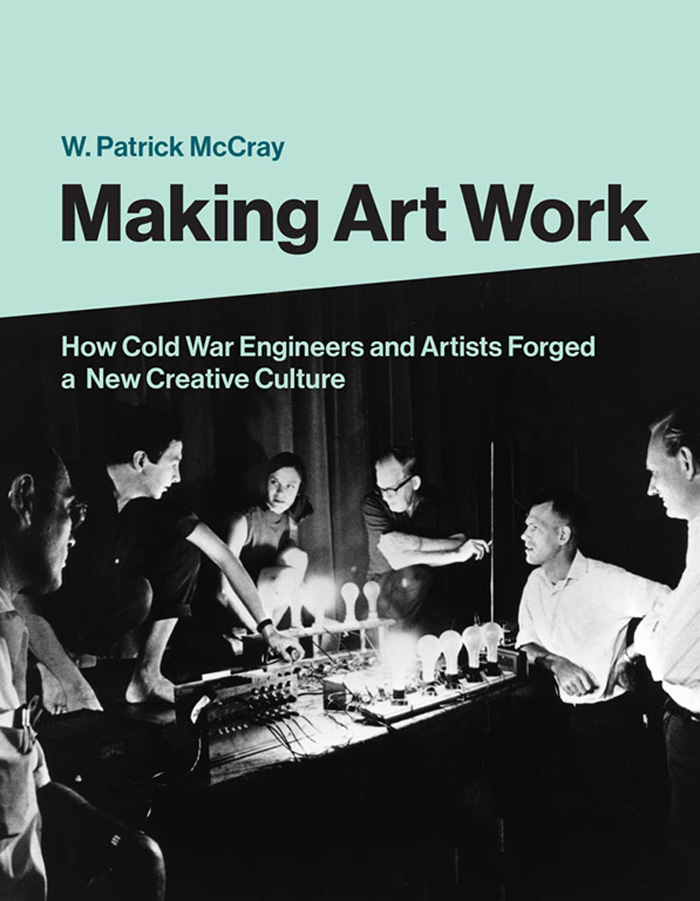

W. Patrick McCray - Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture

Here you can read online W. Patrick McCray - Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: MIT Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture

- Author:

- Publisher:MIT Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

W. Patrick McCray: author's other books

Who wrote Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

W. Patrick McCray

The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in ITC Stone and Avenir by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-04425-7

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

Even more than with previous books Ive written, the number of people who assisted and encouraged me throughout a decade of research, writing, and editing was considerable.

None of this would have been possible without the gracious assistance of archivists and librarians at the Library of Congress, the Getty Research Institute, and the Smithsonians Archives of American Art. My special thanks to Henry Lowood, Jessica Gambling, Jeremy Grubman, and Lois White. In addition, I was helped by three student research assistantsClare Kim, Naomi Kuromiya, and Viola Ardeniwho tracked down archival materials with considerable skill and persistence.

I am especially grateful to the archivists and librarians who helped me locate research materials and, when time was pressing, secure images and permissions. I want to especially acknowledge Jessica Gambling and Piper Severance at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Emily Park and Virginia Mokslaveskas at the Getty Research Library for easing my acquisition of images for the book. Mark Hanauer generously contributed a photograph for the dustjacket. Matthew Christensen did a superb job as copy editor. Especial thanks go to Katie Helke and her colleagues at the MIT Press who helped shepherd this book through acquisition, production, and completion.

Two fellowships from the Smithsonian Institutionone from the National Air and Space Museum (in 20152016) and another from the Lemelson Center at the National Museum of American History (20182019)came at just the right times in the writing process.

Heather Krebs, the late Jack Masey, A. Michael Noll, Eugene Epstein, John Holloway, Ruth Waldhauer, Elsa Garmire, and Robert Kieronski all shared materials from their personal collections. In addition, Roger Malina and Julie Martin kindly provided unparalleled access to historical documents, family photographs, and artworks while also swiftly responding to many questions and requests for clarification. While they may not agree with all of my conclusions, the resources they shared helped build the foundation this book rests upon.

Friends and associates who offered ideas, shared research materials, read excerpts, and talked with me about this book project include Ann Johnson (19652016), Lee Vinsel, Meg Rotzel, Hyungsub Choi, David Brock, Jeanne C. Finley, Steven Duval, Jimena Canales, Anne Collins Goodyear, Amy Slaton, Peter Sachs Collopy, Dawna Schuld, Trevor Paglen, Fred Turner, Roger Malina, Eddie Shanken, Peter Westwick, John Blakinger, Julia Buntaine Hoel, Oliver Gaycken, Douglas Kahn, Asif Siddiqi, Stephen Nowlin, Amy Heibel, Peggy Weil, Andres Burbano, Michael Naimark, Fraser MacDonald, Fabrice Lapelletrie, Suman Seth, Evelyn Hankins, Johan Krnfelt, Matthew Shindell, and David Kaiser. Id also like to acknowledge colleagues in the University of California Santa Barbaras Media Arts and Technology Graduate Program, whose work at the art and engineering interface has given me much to think about. My thanks to you all and anyone I may have forgotten.

Three wonderfully kind colleagues took time from their own projects to read a draft of the entire book. Michael Gordin suggested creative ways of thinking about connections between the terrain of art history and more-familiar narratives about technology and science. Bruce Robertson likewise expanded my understanding of the histories of the modern visual arts and dance. And Matthew Wisnioski graciously provided detailed comments on the manuscript and suggestions as to new archival sources.

And, finally, to NicoleI know, I know...

W. Patrick McCray

April 2020

Santa Barbara, California

and Fort Collins, Colorado

The history of science is riddled with chance discoveries, discoveries that link science and art in a common irrationality.

Douglas M. Davis, 1968

Imagine you have a long, thin piece of plastic string. Now attach this spaghetti-like strand to a small electric motor. Then, wire this motor to an Ethernet cable so that whenever digital packets of informationan email, a music downloadstream through the cable, the motor gives a tiny tug and makes the string twitch.

This was Live Wire, created by Natalie Jeremijenko in 1995 when the internet and the World Wide Web were still unexplored realms for most people.

Jeremijenko built Live Wire as both application and art. She, likewise, a hybrid, studying physics, chemistry, and fine arts in Australia before moving to the San Francisco Bay Area and consulting for Xeroxs ubiquitous computing initiative.

Writers descriptions of Jeremijenko were as vague as her professional credentials were varied. In 2006, Salon labeled her an artist as mad scientist.

Artwork as opposed to instrument or experiment? Engineer versus artist? Even today, we often see these as two different cultures separated by impervious walls. But some fifty years ago, the borders between technology and art, long imagined as solid, began to be breached, even if they have not yet melted entirely melted into air. New collaborative communities of engineers, scientists, and artists, fragile at first but eventually durable enough to take root in universities, museums, and companies worldwide, emerged. This transformations history spills beyond the frame of art and technology, providing color and depth to our picture of the eras broader economic and social contexts.

***

Six decades ago, the professional boundaries between engineer and artisttheir communities, activities, institutions, skills, and shared interestsseemed much more unyielding than they are today. Hadnt Charles Percy (C. P.) Snow, the British chemist turned government advisor and novelist, famously generalized that Great Britains intellectuals and political leaders were conversant with the arts and humanities but remained willfully ignorant about technology and science? Even worse, as Snow claimed in 1959, the gaps between humanists and scientistsor, as labeled more recently, between fuzzies and techieshad dangerously widened to the point of mistrust and incomprehension. Although Snow aimed his critiques primarily at humanists and scientists, his categories expanded to include artists and engineers.

Today, bridging the two cultures is, at best, a synecdoche for some form of interdisciplinarity. At worst, its a clich overused by academic administrators and business leaders. More valuable when viewed in its historical context than for its analytical heft, Snows claims retained rhetorical punch well into the 1960s. Once removed from its original British setting, two cultures became a phrase in the United States that helped generate research funds, launch government-funded studies of creativity, and provoke calls to revise university curricula. Art-and-technology advocates imagined their intervention could help solve the two cultures problem, or at least lessen the animus. Viewed by some as too important to be left just to artists, making art was something to which engineers and scientists could and should contribute. Advocates claimed collaborative experiments, which allowed artists to explore new aesthetic possibilities that technologies such as lasers, microprocessors, and computers afforded, could electrify artworks while rewiring the work of making art itself. These activities, they argued, could simultaneously rehabilitate the publics increasingly negative view of technology and its presumed masters: engineers.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture»

Look at similar books to Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Making Art Work: How Cold War Engineers and Artists Forged a New Creative Culture and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.