Contents

The People Are

Not an Image

The People Are

Not an Image

Vernacular Video after

the Arab Spring

Peter Snowdon

First published by Verso 2020

Peter Snowdon 2020

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-316-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-318-2 (UKEBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-319-9 (USEBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932070

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

In memory of

Hani Shukrallah

(19502019)

mentor, comrade andabove allfriend

Doubtless Resnais and the Straubs are the greatest political filmmakers in the modern Western cinema. But, bizarrely, their greatness is not the result of the presence of the people in their films: on the contrary, they make great political films because they know how to show us that the people are that which is lacking, that which is not there.

Gilles Deleuze

I understood it! I finally understood it and I returned to the Square day after day just to make sure that what I was witnessing was not a dream. What I have seen to be the people really were the people, alive and well, and it wasnt just an afternoon uprising that would vanish with the onset of evening. I realized all of a sudden, then and there, that I never really gave the people their right space in my imagination. The people, the collective, are absent in my novels: there are characters, individuals but none of the novels has the people in it Until that day, I saw the people only as a handful of stragglers seeking their own individual interests. When Egyptians became themselves the people, our world, the world of the narrators and storytellers of Egypt, completely transformed.

Ibrahim Shukri Fichere

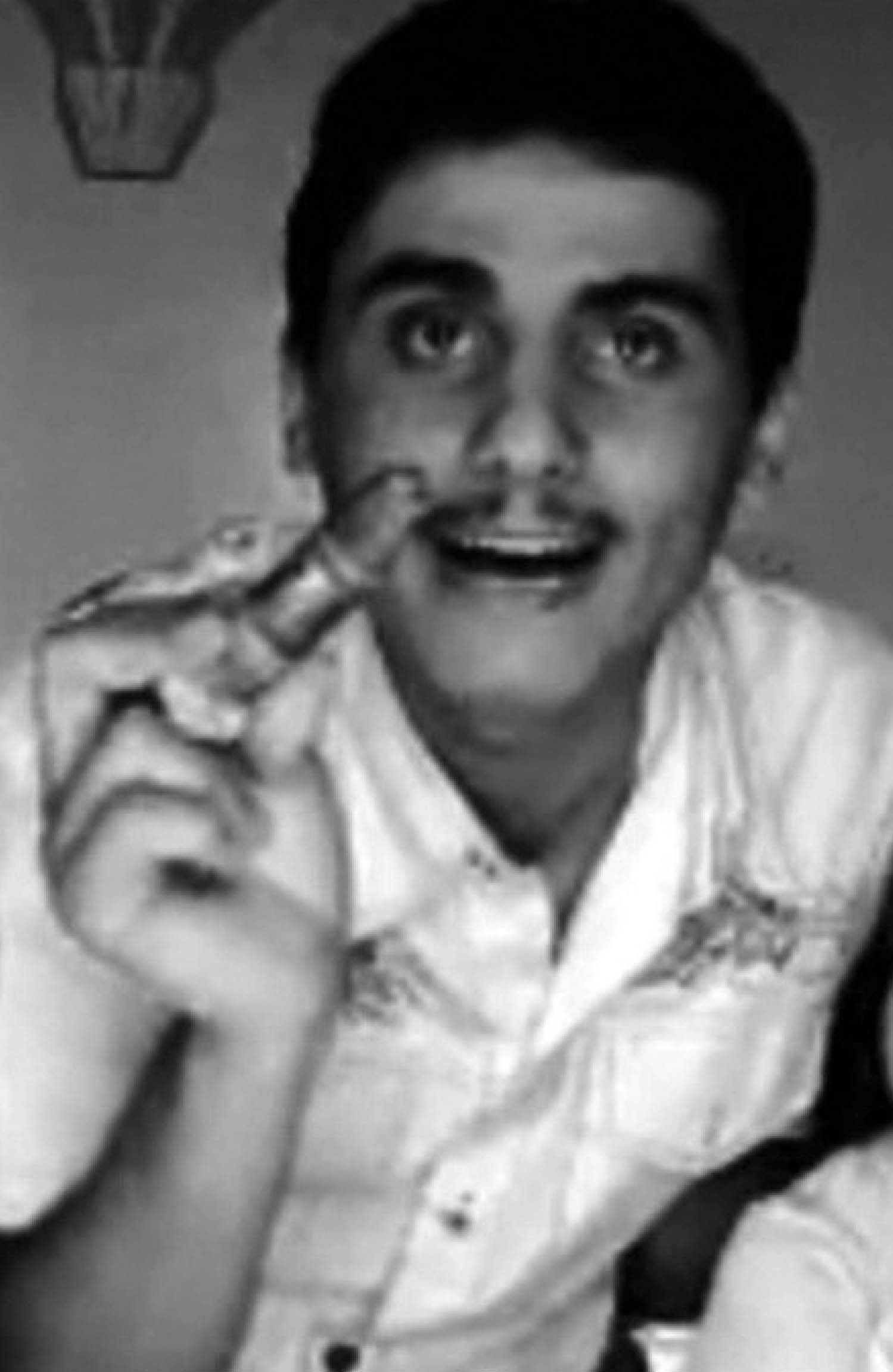

Still frame from video posted to YouTube, February 18, 2011. To view, and for more information, go to vimeo.com/channels/thepeoplearenot, .

Contents

Still frame from video posted to YouTube by 5000zukoo, September 21, 2011. To view, and for more information, go to vimeo.com/channels/thepeoplearenot, .

Filming in the First-Person Plural

Not the least extraordinary thing about the Arab revolutions of 201012 is the fact that they gave rise to an exercise in popular self-documentation on an unprecedented scale. In this, they have an obvious precursor in the Iranian Green Movement of 2009, which might be considered an outlier within the same series, a first tremor announcing the larger earthquake to come.

This ongoing sequence marks the first time since the invention of the cinema that the people have not largely left it to experts, professionals, and outsiders to film their attempts to overthrow an oppressive order, but have instead seen it as part and parcel of their revolutionary action, even as part of their revolutionary duty, to film one another as together they made and unmade history, day in and day out.

For the viewer, the result has been an almost overwhelming proliferation of material, made accessible in quasi-real time through online video-sharing websites. These videos do not simply sit there on YouTube, either, waiting for us to stumble on them: they are always already in circulation, posted and reposted on Twitter and Facebook, as well as being passed on through more private communications channels, such as e-mail or various messaging apps. They are not static objects waiting to be discovered and analyzed: they are fully subsumed within a much larger dynamic process, in which what matters most is not any specific video itself, so much as the energy (both physical and affective) that they gather and transmit as they travel through the complex onlineoffline ecosystems these events have carved out across the region and beyond. These videos are, then, not primarily videos, so much as one vector among many for the ongoing work of mutual self-mobilization that makes radical political change possible, or at least, conceivable.

This double character, matching massive volume with high velocity, makes this phenomenon even harder to pin downif indeed it makes any sense to refer to these videos as a single phenomenon at all. After all, no single viewer, however dedicated, is ever likely to be able to view enough of these videos to establish with reasonable confidence what might constitute any given sample of them as representative. At the same time, one does not have to watch so many of them before coming across one or more that do not simply record events that were (or aspired to be) significant or even exceptional, but that also produce an exceptional effect upon the viewer, even when that viewer is remote, unfamiliar with the context, and has little or no prior emotional connection with the content.

In this book, I set out to explore some of the effects produced by certain of these videos and which are specific to them as video, however much they may remind us of experiences we have encountered elsewhere, whether offline or in other types of media. And I argue that these effects, and the affects associated with them, are, above all, political. More specifically, I suggest that the political work that these videos doboth those that strike us as exceptional and those which we are more inclined to treat as unremarkable, as almost too ordinary to merit any specific attentionis effected not simply through the documentation of offline events (demonstrations, occupations, speeches, songs, poems, debates, arguments, confrontations, acts of State repression, and deaths, to name but a few) and thus through the information about the world away from keyboard that they inevitably contain, but is indissolubly bound up with their aesthetic properties as videothat is, with those of their properties that are at once both sensory and formal.

To speak of the aesthetics of these videos, whether singly or as a group, is not to ignore their importance as human documents and/or political gestures, to reduce them to an object of disinterested appreciation, or to trivialize the very real risks that those who made them took, and oftentoo oftenpaid for with their lives. Rather, it is to focus on their nature as gesturesthat is, as concrete ways of carving out singular blocks of perceptible, sensible spacetime, each of which is imprinted with its own specific dynamic character. Alongside the more obvious reasons contained in their subject matter which may have led them to be recorded and subsequently posted on the Internet in the first place, these videos also contain a wealth of information that can neither be mapped without remainder onto their explicit first-order message (On such and such a date, in such and such a place, such and such an event happened), nor dismissed as mere noise. To ignore the formal-kinetic-affective dynamics that traverse them and single them out for us, the viewer, is, I would argue, to ignore that which is most irreplaceable and most valuable about them and so risk misconstruing what they have to tell us about one of the most important recent passages in the history of human emancipation.