Niccolò Machiavelli - The Life of Castruccio Castracani

Here you can read online Niccolò Machiavelli - The Life of Castruccio Castracani full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Alma Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

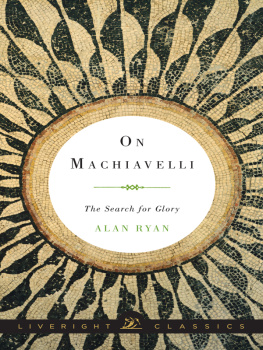

- Book:The Life of Castruccio Castracani

- Author:

- Publisher:Alma Books

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Life of Castruccio Castracani: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Life of Castruccio Castracani" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Life of Castruccio Castracani — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Life of Castruccio Castracani" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Life of

Castruccio Castracani

The Life of

Castruccio Castracani

Niccol Machiavelli

Translated by Andrew Brown

ALMA CLASSICS

an imprint of

ALMA BOOKS LTD

3 Castle Yard

Richmond

Surrey TW10 6TF

United Kingdom

www.101pages.co.uk

The Life of Castruccio Castracani first published in Italian in 1520;

Florentine Histories first published in Italian in 1525.

This translation first published by Hesperus Press Limited in 2003;

this revised edition first published by Alma Classics in 2020

Translation, Introduction and Notes Andrew Brown, 2003, 2020

Cover design by Will Dady

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 978-1-84749-832-8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

The Life of

Castruccio Castracani

Nietzsche, the philosopher of the will to power, whose admiration for Machiavelli comes as no surprise, complained how difficult it was to capture the Italians style in German. How could the German language [...] imitate the tempo of Machiavelli, who in his Prince allows us to breathe in the fine, dry air of Florence and cannot hold back from presenting the most serious affairs in an unrestrained allegrissimo, not perhaps without a malicious artistic sense of the contradiction he is risking thoughts that are long, heavy, hard and dangerous, conveyed at the tempo of a gallop and with the most mischievous sense of humour (Beyond Good and Evil, Section 28).

Nietzsche loved the Italian language, to which he remained, in practical terms, a relative outsider. He strewed his own writings with Italian tags, and tried to capture for German something of the brio of the southern language as he perceived it. This was quite a challenge given that, even more than the French of his beloved moralistes and Stendhal, Italian was for him the anti-Teutonic language par excellence. German is heavy, contorted, pedestrian, lumbering, serious, Hegelian; Italian is light, direct, skipping, dancing, mocking Machiavellian.

His observations here have as much to do with his penchant for berating his fellow Germans as with the inherent qualities of Machiavellis prose. Whether in The Prince, or the Discourses, or the Florentine Histories, or even the short Life of Castruccio Castracani, it is doubtful whether allegrissimo is the right word for Machiavellis tempo. His Italian is concise, epigrammatic and dry, but it cannot be read quickly. The sentence structures can be as involved and hypotactic as in much German writing; the plethora of vowels slows the voice (or the inner voice) down to something closer to an andante moderato; the exposition is (apart from flights of passion such as the appeal for Italian unification at the end of The Prince) couched in the calm tones of precise analysis. Through the divisions and subdivisions of regime classification in The Prince, or the insistence on causal chains in the career of Castruccio (seeing that, because of, in order that, for fear of), one can hear the pad of an alert, wary, gleaming-eyed feline. Italian can sound both airy and orotund, deliberate and ironic, passionate (grand opera: Nessun dorma!) and mouth-wateringly sensuous (mascarpone, fettuccine, zabaglione). In his theoretical and historical works, Machiavelli employs all these registers, except perhaps the last (as Nietzsche says, he is dry), but he also imposes a Latinate rhetoric a love of balance and antithesis, the use of chiasmus, a reliance on the personification of abstractions such as Fortune onto his sentences.

The stylistic dryness may at times result in a perceived disjunction between the (to his contemporaries) often hair-raising subversiveness of what he was doing namely, attempting to undermine a millennium and a half of Christian teaching on the nature of moral life, especially in so far as it relates to politics and the debonair way he put his message forward. Machiavelli is not to be read quickly (and it is worth remembering that Nietzsche was a great advocate of slow reading, in any language). He believed his Prince, or any political leader, should wait for the right moment for action, and not be overhasty or impulsive; his style, too, has, for all the provocation of the subject matter, a cautious disposition, arranging its words with the care of a military tactician. (This can be captured only approximately in English, which conducts its syntactic campaigns in accordance with different rules.) And it is not just a matter of word order. Machiavelli was convinced that, wherever we go, we need to be on our guard against false friends. Castruccio, his warlord hero, was exemplary in his awareness of the prevalence of treachery in public affairs. He shows no compunction at breaking his word; if he does not, others will, and he will be eliminated hence the need for a pre-emptive strike. Words change (stato state, or status? the word was mutating), and so do human affairs; so, be adaptable. Politics is full of false friends; so, too, is language. Machiavelli himself focuses on how people use lofty language to conceal self-serving ends this is a skill which his Prince must deliberately adopt. And Machiavelli himself tests to breaking-point the terms of ethical discourse he has inherited, most notoriously the word which, more than most, lies at the very foundation of all moral discourse: the word virt (virtue).

If we look at some of the dozen or more examples of Machiavellis use of this word in The Life of Castruccio Castracani, we gain a sense of the constellation of meanings that it comprises. The young Castruccio, good at athletics and all the arts that would make him a successful warrior, shows virt of mind and body. Messer Francesco of Pisa is exemplary in wealth, grace and virt. It is soon obvious that virt does not denote Christian virtue, or, if it does, the term is being used with an elasticity that is exhilarating and perplexing, even if we accept that any definition of virtue is going to be fuzzy, problematic, endlessly revisable (that, after all, is what moral philosophy is all about). For Machiavelli, the notion of virt draws on the Latin virtus it refers to the qualities of a man (vir). Its etymology need not as such condemn it to an exclusively masculinist fate; still, virt in Machiavelli is often the quality that needs to be shown by a soldier. At one point in the Life, Castruccios enemies flee without having been able to show their virt. Later on, we are told that certain men in battle resist their opponents not out of virt but out of mere tenacity. So virt cannot be mere unthinking bravery: it involves a certain intelligence, too the ability to seize the way things are going and take advantage of them. (Sometimes Machiavelli uses the word

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Life of Castruccio Castracani»

Look at similar books to The Life of Castruccio Castracani. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Life of Castruccio Castracani and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.