PIETER BRUEGEL

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Series Editor: Franois Quiviger

Already published

Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason Mary Ann Caws

Caravaggio and the Creation of Modernity Troy Thomas

Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares Nils Bttner

Isaac Newton and Natural Philosophy Niccol Guicciardini

John Evelyn: A Life of Domesticity John Dixon Hunt

Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Time Bernadine Barnes

Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer Christopher S. Celenza

Rembrandts Holland Larry Silver

PIETER

BRUEGEL

and the Idea of

Human Nature

ELIZABETH ALICE HONIG

REAKTION BOOKS

For Deb

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2019

Copyright Elizabeth Alice Honig 2019

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789141085

COVER: Pieter Bruegel, detail of Childrens Games, 1560, oil on canvas; akg-images.

CONTENTS

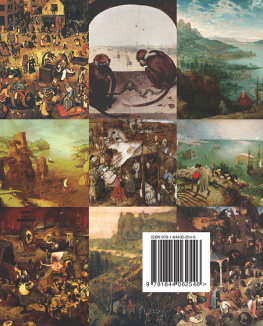

1 Casting roses before swine: detail from Pieter Bruegel, Twelve Proverbs, 1558, oil on panel.

ONE

Humanity and Self-knowledge

DINNER PARTY IN Antwerp around 1560, with twelve guests. Some of them, and perhaps their host, are officers of the Antwerp mint, the citys money-makers in a most literal sense. The group is well-to-do, and most are educated but not intellectual; they are politically informed but not partisan.).

DINNER PARTY IN Antwerp around 1560, with twelve guests. Some of them, and perhaps their host, are officers of the Antwerp mint, the citys money-makers in a most literal sense. The group is well-to-do, and most are educated but not intellectual; they are politically informed but not partisan.).

The images are puzzles, challenging the guests to make sense of what they show. Since the time of this dinner party, Then somebody says, Wait, my man is banging his head against a brick wall! and the next declares that his is filling the hole after the calf has drowned we would say, closing the stable door after the horse has bolted. Laughing at the cleverness with which common parlance has been made visual, the guests continue to work out what is being illustrated, sometimes understanding that not one but several common sayings are referred to within a single image, like the man who falls between two stools and also lands in a pile of ashes.

Once the basic proverbs have been discovered, the party begins to discuss the implications of all these sayings, their common themes and unexpected interconnections. Proverbs that look and even sound quite dissimilar share the same insights into human behavioural tendencies. People are inconstant, the guests agree, always trying to play two sides at once or following the shifting winds. They waste their best efforts in useless endeavours. Hypocrisy is common, as are envy and anger and deceit. And these failings cannot be isolated to some group defined as other, be it peasants or women or soldiers. The commonalities that knit one proverb to another, the bare legs and watery pits as well as the metaphorical failings, move the company to acknowledge that what they are discussing is simply human nature, our common flaws and the things these flaws make us do. As the evening progresses, laughter intermingles with more serious conversation as the guests acknowledge the consequences of humanitys failings and ponder which weaknesses they most need to remedy within themselves.

The year 1558 is inscribed on one of these proverb plates, and a date of 1557 found on another single-proverb roundel, also originally part of a set, makes it Bruegels earliest surviving painting. Coeckes work and thought were marked by a deep understanding of Italian as well as local artistic traditions, and although Pieter Bruegels art bears little trace of the former, his teachers intellectual internationalism was important. Perhaps it was what inspired him to travel to Italy himself after Coeckes death in 1550, journeying as far south as Naples, collaborating with the great miniaturist Giulio Clovio in Rome, and making the vivid Alpine landscape drawings that would form the basis of his prints for Hieronymus Cock upon his return to Antwerp.

2 Banging head against a wall: detail from Pieter Bruegel, Twelve Proverbs, 1558, oil on panel.

Heroic bodies, grand gestures and memorable individual deeds clearly interested Bruegel not at all: in what contemporaries saw as a contest between a more Italianizing manner His vernacular images used that style to articulate ideas that were much more broadly shared among the literate public of early modern Europe. In particular his art was well suited to presenting a perspective, or opening up questions, on the subject of human nature. Bruegels very choice to focus much of his attention on the most common, ordinary people of his day meant that beholders were viewing characters who were untutored, not fully formed by the precepts of civil society, so that the essentials of humanness made themselves more keenly apparent. Bruegel furthermore rarely seems to care about a single individual. Even in pictures where he depicts a narrative with key actors, and even when those actors express clear emotional states, they are only rarely characterized as singular persons: usually, they are treated as types. The viewer is not asked to identify or empathize with an individual in a given situation, but to contemplate and understand a state of being. We are allowed to connect to Bruegels paintings on the level of shared humanity.

3 Pieter Bruegel, Twelve Proverbs, 1558, oil on panel.

Bruegels pictures entered into this ongoing conversation by inviting others to regard his perspective and, from there, to take one of the two routes I have imagined above: to enter into social discussion, perhaps deploying their own knowledge of written arguments, or to look inward and consider their own selves. Bruegel has certain expectations of his viewers nature and sets up situations of spectator ship for the individual based on those expectations. He often structures his pictures so that they insist upon a detached perspective on the world, on humanity, on history a viewpoint that can also promote self-questioning or what we might call introspection. At the same time, though, his works are perfectly geared to allowing each beholder to partake in discourse with others. As opposed to the tightly knit symbolic ensembles of Jan van Eycks generation, rigorously pieced together so that every element adds its part to the larger sense of the work, Bruegels paintings are dense with meaningful details that do not cohere to form a single argument. They are, therefore, endlessly discussable. At the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where many of his paintings hang today in a single gallery, visitors are constantly seen to point, discover, share and talk before these rich works. Bruegels original audience had quite different social and philosophical contexts for their discussions, but the structure of stimulus was the same.

Next page

DINNER PARTY IN Antwerp around 1560, with twelve guests. Some of them, and perhaps their host, are officers of the Antwerp mint, the citys money-makers in a most literal sense. The group is well-to-do, and most are educated but not intellectual; they are politically informed but not partisan.).

DINNER PARTY IN Antwerp around 1560, with twelve guests. Some of them, and perhaps their host, are officers of the Antwerp mint, the citys money-makers in a most literal sense. The group is well-to-do, and most are educated but not intellectual; they are politically informed but not partisan.).