Ostrich fern fronds unfurl in spring and mingle with dwarf white pine needles and candles.

The fallen flowers of an old rhododendron make a pool of lavender beneath its gnarled trunks. Opposite: The far shrub borders in fall are a pollinator- and wildlife-friendly mix of fruiting shrubs, conifers, and ground covers.

A Way to Garden

A HANDS-ON PRIMER FOR EVERY SEASON

Margaret Roach

TIMBER PRESS

Portland, Oregon

Show me your garden, and I shall tell you who you are.

ALFRED AUSTIN

For amazing Grace, herself a bold example of the life cycle at work

Contents

A female green frog perches on the lip of a water- and Azolla-filled trough she has claimed as home.

Preface

AND NOW, 21 YEARS LATER

MY HOW TIMES HAVE CHANGED. Though at first thought, the idea of rekindling a 21-year-old garden book might not seem like a task as radical or needed as, say, redoing one of the same vintage about computers, it turns out otherwise. Yes, we still use shovels (if not Word 6.0; Im now pecking away on version 16.16.2).

Yes, the horticultural operating system still begins with green side up, though I did recently gift a friend some paperwhite narcissus to force, forgetting to state what seemed to me the obvious. I got a call a few weeks later asking why white spaghetti was sprouting from the pot.

And one more yes, before we get to all the nos. Were they alive, my moneys on the likelihood that Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein would still be discussing the most perennial of evergreen garden topics:

The story goes that Toklas once asked Stein what she saw when she closed her eyes.

Weeds, Stein replied.

Me, too; now and forever, I forecast that the gardener shall forevermore have plants growing in the wrong place, ad infinitum, ad nauseam. Help!

Much else has been upended, I came to realize as I dug in to revise the book. No, mere updates would not do, Margaret. The catalog sources at the back of the first edition are now mostly fond memories of old friends long gone from the business. (Their progeny live on in my garden, and I still unearth the occasional old plastic label, the printing so faded as to be nearly illegible.)

Some it plants of that moment that everyone grew (or wanted to, if only they could secure a piece) are now known thugs, and I, like gardeners everywhere, will spend the rest of my days hoicking them out, sometimes losing the battle. Their tenacity is an in-our-faces, perennial reminder of inadvertent environmental wrongdoingof cultivating what proved to become invasives.

Plants that were rarea dramatic variegated- or gold-leaf version some savvy gardener identified from a sport, perhapsstayed that way a relatively long while. The ramp up to wider distribution was once upon a time dictated by the math of the plants inclination to set seed or provide ample divisions or cuttings. As tissue culture laboratories have proliferated, and the secrets of micropropagation, or cloning, for more species unlocked, the pace for many plants has likewise accelerated. Advancements in other methods of mass production, like of wholesale baby plants called liners or plugs, has evolved, too, in ever more mechanized greenhouse facilities. You barely have time to gloat over being among the first to have something special, before it confronts you en masse at the big-box store.

Rodgersia podophylla sends up creamy plumes in early June, but its bold foliage is the main attraction from emergence till hard frost.

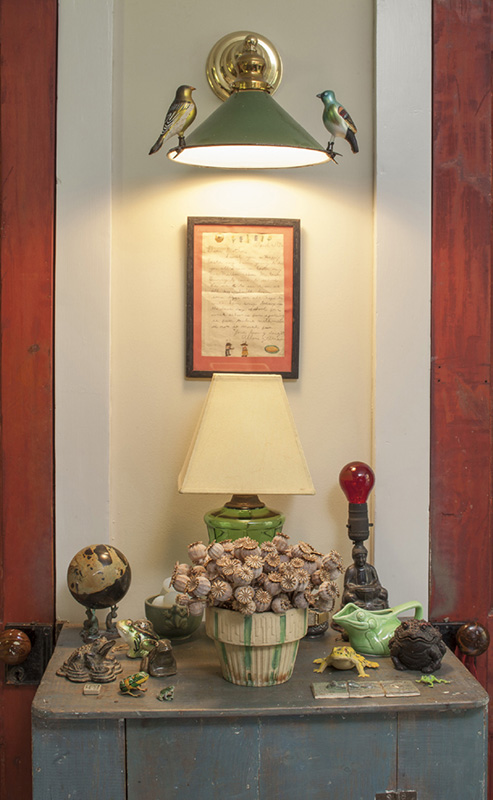

Frogs and birds and poppy pods: Indoors and out, elements of the natural world are ever-present at my house.

A spring peeper, Pseudacris crucifer, rests on a leaf of European wild ginger (Asarum europaeum) outside the kitchen door.

I knew, and grew, some native plants back thennotably winterberry hollies and astersbut our current collective consciousness about the role of natives, about habitat gardening and pollinator gardening, had not taken hold. Today native status is even printed on plant labels (though often imprecisely, since few things are native to the entire nation). The word nativar, for a cultivar of a native plant with showier attributes or a different habit than the straight species, has been added to the vocabulary.

Ticks were familiar, but those tiny arachnids hadnt yet traumatized a chunk of the nation. Our longtime No. 1 annual, the impatiens, hadnt been assaulted by a devastating fungus-like disease called impatiens downy mildew, and a related species of DM hadnt yet attacked beloved basil. (As I type this, news is just out that the impatiens genome sequence and assembly has been cracked, a critical step in developing a strategy to breed in resistance someday to DM.)

And so many introduced forest pests have increased their pressure: The ever-wider encroachment of hemlock woolly adelgid, as one example, saw to it in these ensuing years that I would not dare plant Tsuga. Instead I mourn former stands of what was a foundation species of the northeastern forests I live surrounded by.

Even the earthworm has evolved from being regarded as a gardeners (and farmers) best friend to a leading suspect in environmental havoc. I didnt even know years back that there were no native earthworms in the northern United Statesthat they were all introduced species (including many kinds in warmer regions). And nobody knew just how destructive some of the latest imports, notably jumping worms from Asia in the genera Amynthas and Metaphire, would prove to gardens, yes, but to forest ecologies most terrifyingly, as they impoverish soil and interrupt the process of succession in parts of the Great Lakes Forest, the Great Smoky Mountains, and New England. We will be hearing more about them regularly, I forecast.

The now-muscular trunk of a European copper beech was just a youngster when planted decades ago on the hillside above the house.

Need I mention that the gardeners other once-reliable companion, the weather, doesnt seem very friendly or familiar at all, either, as the climate shifts? The expected meteorological pacing of each space of a season is no longer, and all the time we face extremes that are ever more perplexing to manage around.