Bibliography

Asakura, Kazuyoshi, History of Iaido. Magazine article translation by Colin M. Roach and Soichi Nishimoto (Tokyo: Iaido Tora No Maki Journal: Volume 1 , June 2008).

Aston, W. G., Nihongi, Chronicles of Japan from the Ancient Times to A.D. 697 , vol. 1 (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1972).

Buttweiler, Tom, Ezo Fittings Bushido, An International Journal of Japanese Arms 1.2 (1979).

Campbell, Joseph, Sake & Satori (Novado: New World Library, 2002).

Christopher, Robert C., The Japanese Mind (New York: Ballantine Books, 1983).

Cleary, Thomas, The Essential Tao: An Initiation into the Heart of Taoism through the Authentic Tao Te Ching and The Inner Teachings of Chang Tzu (San Francisco: Harper, 1991).

Davey, H. E., Living the Japanese Arts and Ways (Ann Arbor, MI: Stone Bridge Press, 1997).

De Barry, W. M.; Keene, Theodore Donald; Tanabe, George; and Varley, Paul. Sources of Japanese Tradition , vol. 1 (New York: Chichester, West Sussex: Colombia University Press, 2001).

Deng, Ming-Dao, Scholar Warrior: An Introduction to the Tao in Everyday Life (New York: Harper Collins, 1990).

Draeger, Donn F., Monograph Series No. 3 Transcribed by Pat Lineberger Edited by Hunter Armstrong. (Sedona: International Hoplology Society, 1998).

Draeger, Donn F., The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan , vol. 3, University of Hawaii Lecture Series (Sedona, Ariz.: International Hoplology Society, 1978).

Draeger, Donn F., The Martial Arts And Ways of Japan , vol. 4, University of Hawaii Lecture Series (Sedona: International Hoplology Society, 1998).

Duss, P., Modern Japan (2nd Ed.). (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998).

Friday, Karl, Hired Swords: The Rise of the Private Warrior in Early Japan (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992).

Friday, Karl F., Warfare and History: Samurai, Warfare and the State in Medieval Japan (New York: Routledge, 2004).

Green, Thomas A., Martial arts of the World: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, INC. 2001).

Ikegami, Eiko, The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism in the Making of Modern Japan (Cambridge, MA: First Harvard University Press, 1997).

Izano, Nitobe, Bushido: The Soul of Japan (Boston: Charles Tuttle, 2001).

Kapp, Leon; Kapp, Hiroko; and Yoshihara, Yoshindo, The Craft of the Japanese Sword (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1987).

King, Winston L., Zen and the Way of the Sword (New York: University Press, 1993).

Kishida, Tom, The Yasukuni Swords: Rare Weapons of Japan 19331945 (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2004).

Lowry, Dave, Traditions: Essays on the Traditional Japanese Martial Arts and Ways (North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle, 2002).

Lowry, Dave, In the Dojo: A Guide to the Rituals and Etiquette of the Japanese Martial Arts (New York: Weatherhill, 2007).

Mason, R. H. P. and Caiger, J. G., A History of Japan , rev. ed. (North Clarendon, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1997).

Mitchell, Stephen, The Enlightened Heart: An Anthology of Sacred Poetry (New York: Haper Collins Publishers Inc., 1989).

Moore, Albert C., Iconography of Religions: An Introduction (Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1977).

Nagayama, Kokan, The Connoisseurs Book Of Japanese Swords , trans. Kenji Mishina (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1997).

Nanno, Teruhisa, Iaido Japanese Sword Drawing techniques and Spiritual Practice (Tokyo, Bungeisha, 2004).

Patterson, William, Budos Role in the Growth of Pre-World War II Japanese Nationalism. ( Journal of Asian Martial Arts , vol. 17, no. 3. 2008).

Piggott, Juliet, Japanese Mythology (London: Chancellor Press, an imprint of the Reed International Books Limited Michelin House, 1969).

Rosenberg, Donna, World Mythology, An Anthology of the Great Myths and Epics , 2nd ed. (Chicago: National Textbook Company, 1994).

Stevens, John, Sword of No-Sword, The Life of Master Warrior Tesshu (Boston: Shambhala, 1984).

Suino, Nicklaus, The Art of Japanese Swordsmanship, A Manual of Eishin-Ryu Iaido (New York: Weatherhill, 1994).

Suzuki, Daisetz. T., Zen and Japanese Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970).

Taylor, Kim, The History of Iaido: A Japanese Sword Art, ( Journal of Asian Martial Arts , vol. 1, no. 3. Via Media Publishing Co. Erie, Pennsylvania 1993).

Tsunoda, R. and Goodwrich, C. L., trans. and ed., Japan in the Chinese Dynastic HistoriesLater Han through Ming Dynasties (South Pasadena, CA: Pekins, P. D. and Ione 1951).

Turnbull, Steven, Samurai Warriors (New York: Sterling, 1994).

Warner, G., and Draeger, D. Japanese Swordsmanship: Technique and Practice (New York: Weatherhill, 1993).

Warshaw, Steven, Japan Emerges: A Concise History of Japan from Its Origin to the Present , 10th ed. (Colchester, VT: Diablo Press, 1993).

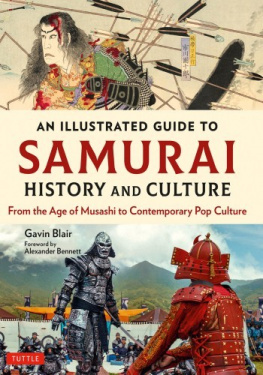

Chapter 1

Appreciating the Japanese Sword

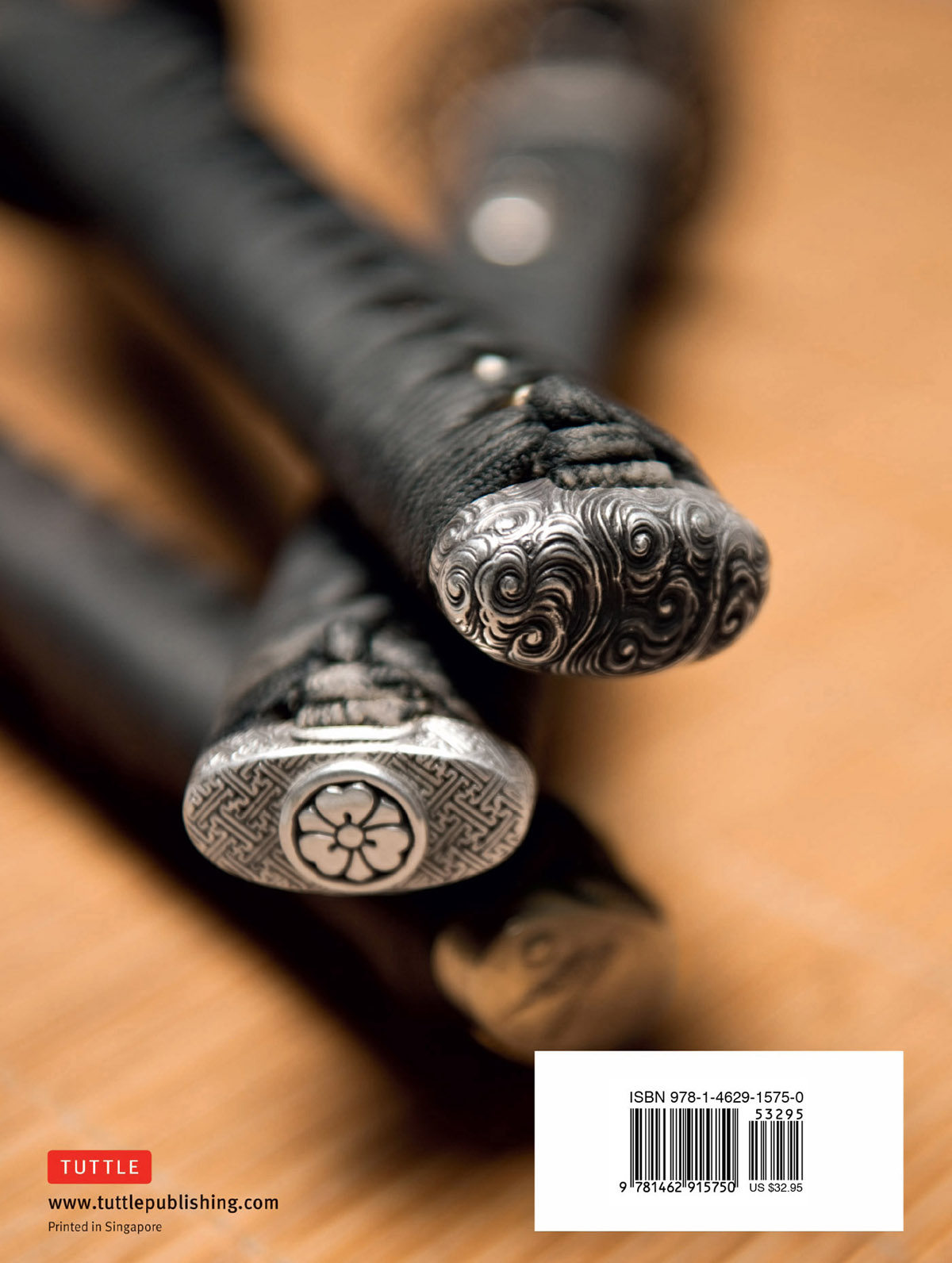

The Japanese Sword is a beautiful weapon without peer in terms of elegance and strength. The flash of the polished steel, the graceful curve of the blade, the aesthetically pleasing wave of the temperline, the swirling flecks of the grain structures, and the exquisitely-crafted fittings immediately impress even rank neophytes. However, to properly embark upon this journey of Japanese sword appreciation, one must study it at its most basic level. We must understand the different types of swords, their parts, nomenclature, and various attributes used to describe shape, quality, and other aspects.

By studying the swords distinguishing characteristics, an understanding of what creates quality and value emerges. This chapter explains which positive and negative attributes allow various agencies to evaluate, rank, and appraise any given blade. Also discussed here is the story of how the sword came to be a collectable art object in the modern era. Expanding on the idea of value and commerce surrounding the sword, this chapter concludes with some guidance for readers by recommending some trustworthy organizations and reputable sword merchants. Later chapters will explain how swords are made, how spirituality shaped its iconography, and how the blade evolved as a metallurgical wonder.

Blade Types

Ken/Tsurugi The ken , sometimes called a tsurugi , is a straight, double-edged sword of ancient Chinese design. It holds particular importance in Buddhism but has also been incorporated into Shinto- ceremonies. Although the ken is one of the oldest sword types to enter Japan, it remains relevant due to its symbolic significance.

Chokut Although also of Chinese design, chokut were produced in Japans ancient times and pre-dated the quintessential, Japanese sword. Chokut are straight and have one cutting edge. Less obvious is that the steel for these early blades is homogenous; not folded and combined to produce greater strength and flexibility. Variations are generally distinguished by the cross-section design. The kiriha-zukuri design would have been more efficient in hacking and thrusting, whereas the hira-zukuri would have a slight advantage in slicing due to its kissaki (tip) design. Some scholars suspect that these two designs were combined (along with several other innovations) to create the first tachi .

Tachi The tachi was the first functional sword of truly Japanese design. Designed for use in slashing rather than thrusting, it incorporated a curved blade and a temperline, highlighting its differentially hardened steel.

Worn edge-down and tied to the outside of armor, it was designed to be drawn and used with one hand (usually from horseback). The tachi s innovative technology and raw effectiveness became a blueprint for all swords developed in later times. Sharp and resilient yet durable and not brittle, the tachi marks the beginning of the Japanese sword.