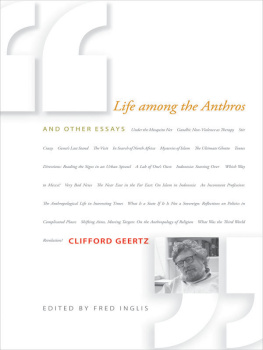

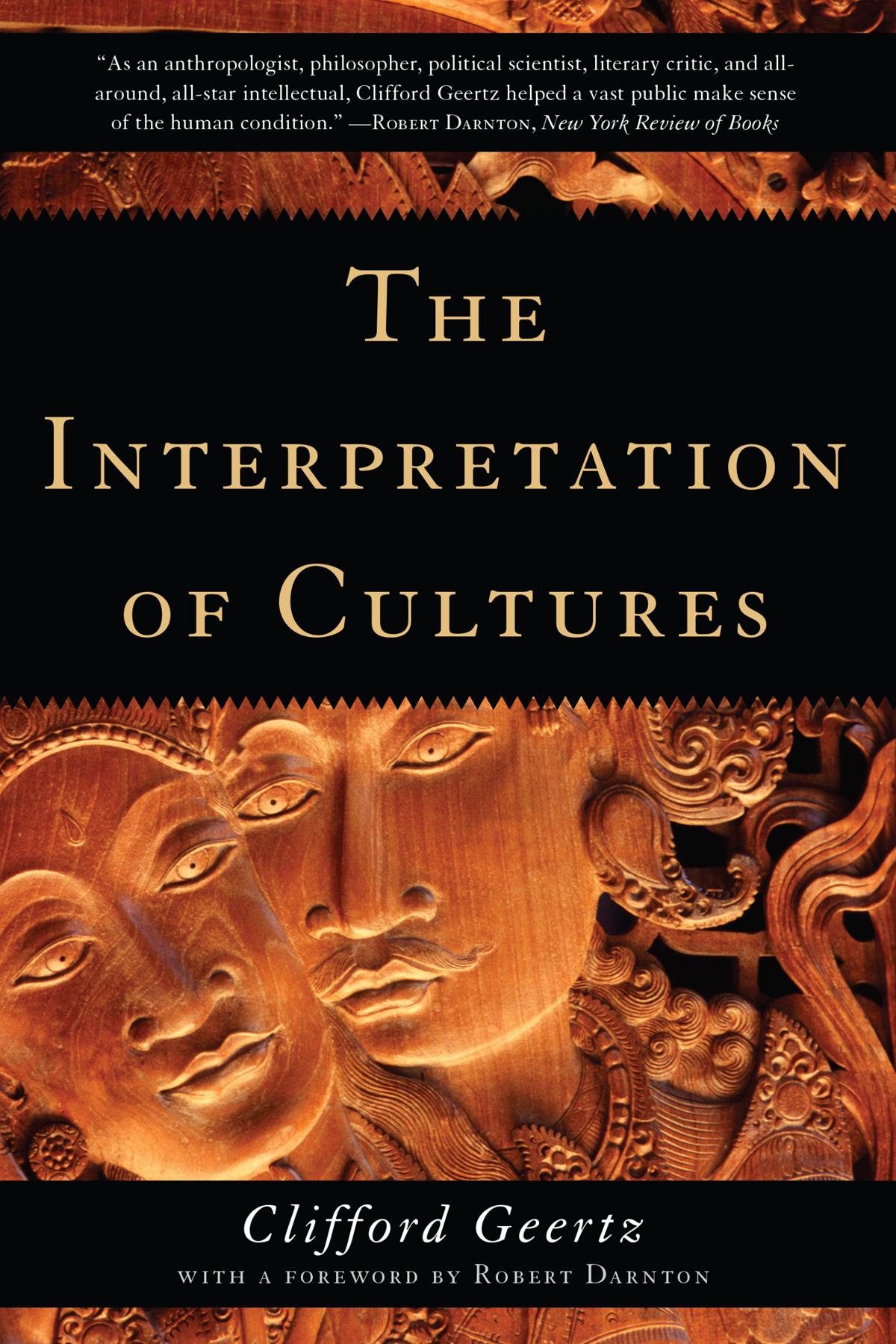

Geertz Clifford - The Interpretation of Cultures

Here you can read online Geertz Clifford - The Interpretation of Cultures full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Hachette Book Group USA, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Interpretation of Cultures

- Author:

- Publisher:Hachette Book Group USA

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Interpretation of Cultures: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Interpretation of Cultures" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Interpretation of Cultures — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Interpretation of Cultures" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 1973 Basic Books

Preface to the 2000 Edition Copyright 2000 by Clifford Geertz

Foreword to the 2017 edition Darnton, Robert. Anthropology, History, and Clifford Geertz, Historically Speaking 8:4 (2007), 3334. 2007 The Historical Society. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

Third edition paperback published in 2017

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-81196

ISBN 978-0-465-09719-7 (1977 paperback)

ISBN 978-0-7867-2500-7 (2008 e-book)

ISBN 978-0-465-09355-7 (2017 paperback)

ISBN 978-0-465-09356-4 (2017 e-book)

LSC-C

E3-20170707-JV-NF

C LIFFORD G EERTZ BELONGED to that rare species known as matres penser. Like a tiny number of other mastersFoucault, Habermas, Bourdieuhe inspired general readers and ordinary scholars operating at lower frequencies throughout the human sciences. Among historians, he left his mark on the generation that came of age in the 1970s and 1980s and who had had their fill of statistical models, functionalist explanations, structures and conjunctures, and dialectical materialism. Fired by Geertzs notions of symbolism and cultural systems, they attempted to do ethnography in the archives.

Yet Geertz never tried to found a school. If he could have been anyone in the 20th century, he once told me, he would have chosen James Joyce. Indeed, Geertzs literary flare got in the way of systematizing. The long, baroque sentences with their parentheses, piled-up adjectives, and convoluted syntax defied imitation. Despite his deep-dyed Weberianism and the years spent under Talcott Parsons, Geertz had no interest in combining propositions into a systematic structure. He cobbled together arguments from different, disparate sources. He was a bricoleur.

Not that he lacked rigor when it came to confronting theoretical issues. His harshest comment after sitting out a disappointing paper at the Institute for Advanced Study was usually underconceptualized. But he did not invent many concepts of his own. He borrowed them from linguistic philosophy, semiotics, Weberian sociology, and any other field likely to be helpful for the task at hand. Then he set to work, using the tools most suited for prying open a foreign way of thinking and exploring an alien mental world.

This approach lent itself to what emerged in France during the 1960s as the history of mentalities. It appealed to anyone who felt inspired by the work of Robert Mandrou, Georges Duby, Philippe Aries, and Michel Vovelle. It also provided something that they lacked: a concept of symbolism grounded in semiotics and an understanding of culture as a system of meaning. The old seminars on the history of mentalities in the Ecole des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales have now been replaced by seminars on history and anthropology.

Geertz did more than anyone to promote the mutual reinforcement of history and anthropology, but he did not initiate it. It developed over many years from the convergence of elective affinities, as he might have put itthat is, a growing awareness of mutual interest in common problems. Anthropologists like Bernard Cohn and historians like Keith Thomas had crossed over the boundaries of their disciplines long before the publication of The Interpretation of Cultures (1973), the book by Geertz that had the most influence on historical writing. True, Geertz had demonstrated the possibilities of ethnographic history much earlier in The Social History of an Indonesian Town (1965), but that book probably was the least read of all his works. Although a great deal of historical reflection went into Islam Observed: Religious Development in Morocco and Indonesia (1968), it was primarily an essay in the comparative sociology of religion inspired by the example of Max Weber. And Negara: The Theatre State in Nineteenth-Century Bali (1980), the most historical of his books, aroused the most skepticism among historians. What then was Geertzs peculiar contribution to anthropological history and historical anthropology?

Most historians probably would reply, thick description. The concept fits Geertzs way of working, but it has been badly misunderstood. When historians try to apply it in their own work, they sometimes choose a subject that seems suitably anthropologicalrites of passage, witchcraft, religious rituals, charivarisand then pile on the descriptive details. As an ethnographer, Geertz certainly believed in empirical rigor, but as a theorist, he insisted on the importance of systems of meaning. In his view, descriptions thickened when the ethnographer seized on the multiple meanings transmitted through a symbol and followed their interplay with other symbols until a cultural system emerged in viewfuzzy at first, but increasingly clear as the interpretations led round and round a hermeneutic circle.

His genius, I believe, consisted in grasping at a thread in such a way as to unravel an entire pattern of culture. How he did it remains a mystery. He spotted peculiarities that made sense to the natives but remained opaque to anyone outside the systemthe use of power to stage ceremonies in Bali, for example, as opposed to the use of ceremony to reinforce power. He had an uncanny ability to imagine himself in other persons skins and to follow their train of thought at points where it ran against the grain of his own culture.

This disposition did not merely lead him into remote villages in Indonesia and Morocco. It played on everything that came within his field of perception, including jazz, sports, politics, literature, and, yes, history. But how can historians make use of it? None of us is built like Clifford Geertz. If one follows the work of the historians most inspired by himJoan Scott, William Sewell, Natalie Davis, Keith Baker, Peter Burke, Rhys Isaac, myselfthere is no Geertzian stamp to be discovered, for there was no such thing as Geertzianism. His work opened up avenues for others to pursue, but the pursuit led in different directions. He set off in many directions himself, scattering his ideas across a vast landscape, just as he gathered them from many different sources. He was a master without disciplesone of a kind.

Robert Darnton, Anthropology, History, and Clifford Geertz, Historically Speaking 8, no. 4 (2007): 3334. 2007 The Historical Society. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

W HEN, AT THE beginning of the seventies, I undertook to collect these essays, all of them written the decade before, during the fabled sixties, I was far from clear as to what it was that interconnected them aside from the fact that I had written them. A number was on Indonesia, where I had been working for some years; a number was on the idea of culture, an obsession of mine; others were on religion, politics, time, and evolution; and one, which was to become the most famous, or infamous (it reduced both marxists and advanced literati to angry spluttering), was a rather off-beat piece on the deeper meaning of cockfighting among the Balinese. Did they add up to anything: a theory? a standpoint? an approach?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Interpretation of Cultures»

Look at similar books to The Interpretation of Cultures. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Interpretation of Cultures and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.