THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES

MICHIGAN PAPERS IN CHINESE STUDIES

NO. 39

MAO ZEDONGS TALKS AT THE YANAN CONFERENCE ON LITERATURE AND ART: A TRANSLATION OF THE 1943 TEXT WITH COMMENTARY

by

Bonnie S. McDougall

Ann Arbor

Center for Chinese Studies

The University of Michigan

1980

Copyright 1980

by

Center for Chinese Studies

The University of Michigan

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

McDougall, Bonnie S., 1941

Mao Zedongs Talks at the Yanan conference on literature and art.

(Michigan papers in Chinese studies; no. 39)

1. Mao, Tse-tung. Tsai Yen-an wen i tso tan hui shang ti chiang hua. 2. ArtsChinaAddresses, essays, lectures. I. Mao, Tse-tung, 1893-1976. Tsai Yen-an wen i tso tan hui shang ti chiang hua. English. II. Title. III. Series.

NX583.A1 M3634 700.951 80-18443

ISBN 0-89264-039-1

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89264-039-3 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12738-2 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90133-3 (open access)

In memoriam

Ruth Constance McDougall

CONTENTS

by Mao Zedong

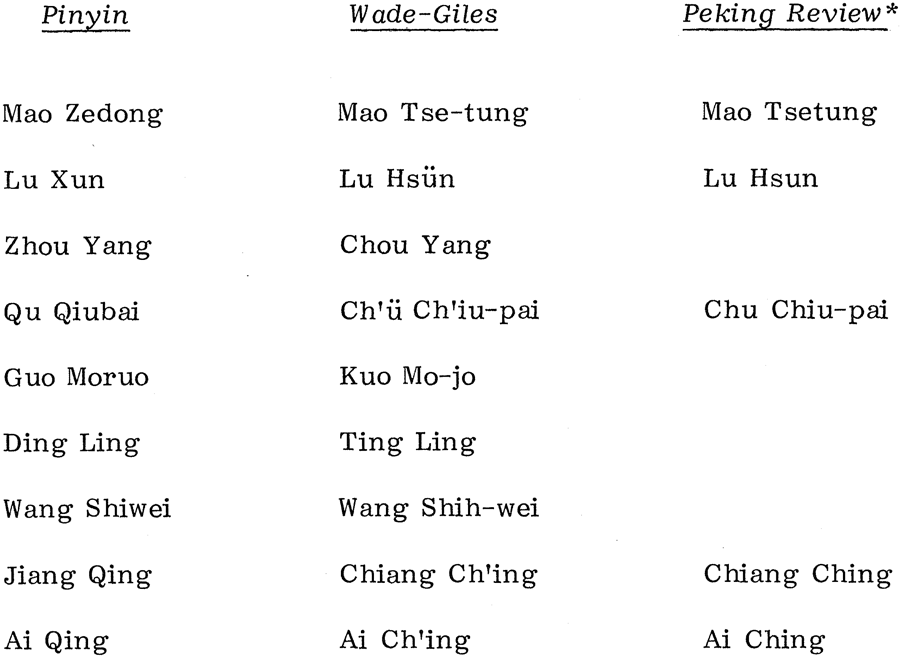

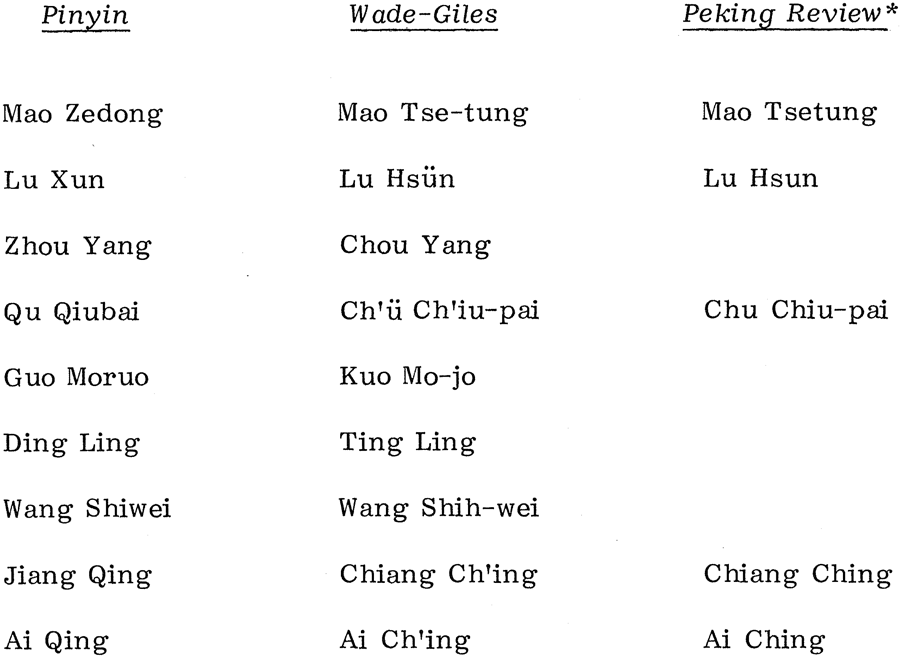

Pinyin romanization has been used throughout, except for some common geographical names such as Peking. For readers more familiar with Wade-Giles romanization, I append a list of the two or three versions of the names of major characters mentioned below.

Note

A modified form of Wade-Giles, used for names of well-known people in English-language Chinese publications.

This work was conceived and carried out at the John K. Fairbank Center for East Asian Research at Harvard University. I am most grateful to Ezra F. Vogel, then director of the Center, for making it possible for me to come to the Center as a Research Fellow in 1976 and for his continued support and encouragement thereafter. I am also very grateful to Roy M. Hofheinz, Jr., current director of the Center, for extending my tenure as a Research Fellow in 1977 and 1978 and for his help and goodwill. I owe a great deal to the other members of the Center, especially to the lunch room regulars on whom many of my ideas were first tested and who generously gave forth of their own. In particular I should like to thank Benjamin I. Schwartz and John E. Schrecker for reading the manuscript and for their valuable suggestions. I should also like to thank John K. Fairbank for his interest and encouragement. A preliminary version of my commentary on the Talks was read to the Harvard East Asian Literature Colloquium in November 1976, and I am most grateful to its members for their suggestions and interest. Throughout the work on this project I have received the greatest encouragement and assistance from Michael Wilding, and I am particularly grateful for his guidance in the world of Western literary criticism. I wish to thank Harriet C. Mills for her encouragement and advice on the publication of the manuscript. I am also very grateful to Barbara Congelosi for her painstaking editorial work. Finally, I should like to thank Anders Hansson for his suggestions and corrections from the time when this project first took shape to its present publication.

B. McD.

June 1980

I have known many poets. Only one was as he should be, or as I should wish him to be. The rest were stupid or dull, shiftless cowards in matters of the mind. Their vanity, their childishness, and their huge and disgusting reluctance to see clearly. Their superstitions, their self-importance, their terrible likeness to everyone else as soon as their work was done, their servile minds. All this has nothing to do with what is called literary talent, which exists in perfect accord with downright stupidity.

Paul Valry, Cahiers, 1:193

Mutual disdain among men of letters goes back to ancient times.

Cao Pei (186-226)

The Yanan Talks as Literary Theory

The writings of Mao Zedong have been circulated throughout the world more widely, perhaps, than those of any other single person this century. The Talks at the Yanan Conference on Literature and Art has occupied a prominent position among his many works and has been the subject of intense scrutiny both within and outside China. Yet, despite its undoubted importance to modern Chinese literature and history, the Talks has never been thoroughly examined with regard to various elements of literary theory therein contained, i.e., with regard to Maos views on such questions as the relationship between writers or works of literature and their audience, or the nature and value of different kinds of literary products. While it can hardly be argued that a cohesive and comprehensive theory emerges in the course of Maos Talks, the purpose of this study is to draw attention to those of Maos comments whose significance is primarily literary, as distinguished from political or historical.

In light of modern Western literary analysis, Mao was in fact ahead of many of his critics in the West and his Chinese contemporaries in his discussion of literary issues. Unlike the majority of modern Chinese writers deeply influenced by Western theories of literature and society (including Marxism), Mao remained close to traditional patterns of thought and avoided the often mechanical or narrowly literal interpretations that were the hallmark of Western schools current in China in the early twentieth century. For example, Western-influenced critics and writers unconsciously assumed elite status and addressed an elite or potentially elite audience, implicitly accepting a division between high or elite audiences and low or popular audiences for literature; on the other hand, Mao seemed to take for granted a relative harmony between traditional Chinese elite and popular culture, such as may also have existed in the Western past but which had disappeared in the modern era. Moreover, Mao appears not to have been troubled by typical Marxist difficulties regarding mind and matter; like Marx himself, he did not feel constrained to establish a consistent material basis for every phenomenon in the nonmaterial superstructure. Finally, unlike most modern Chinese writers, who operated on the basis of a clearly defined (and therefore limited) school, Mao followed traditional practice in his own poetry, for which no explicit theoretical justification was required. As Matthew Arnold noted in a different context, being in touch with the mainstream of national life releases one from the need for continual self-assertion that obsesses the dissident. It may be argued that following traditional literary practice in his poetry left Mao free to form literary judgments on an instinctual and nondogmatic level, whereas the Westernized writers were obliged to rationalize their practice from given, specific theoretical premises. The freedom to draw with ease on his own experience and not restrict himself to any currently available model of Western literary theory or practice could also explain the combination of ontological simplicity in his general thinking on literature and keen insights into specific questions.

Detailed discussions on the Talks first appeared in the West in the fifties and sixties, notably in such works as C. T. Hsias History of Modern Chinese Fiction (1961), the special edition of China Quarterly on communist Chinese literature (1963), One reason for Hsias relatively mild attitude is perhaps that he alone of the writers listed above referred to the original version of the Talks, in which Maos literary theories are spelled out in more detail. I have no wish here to dispute the findings of these writers in regard to the political significance and effects of Maos Talks, and I endorse without reservation their condemnation of the harsh political control exercised over Chinese writers since the fifties; nevertheless, I take issue with them on the importance of the Talks to literature.