FORWARD BY THE AUTHOR

I must have been six or seven when, while perusing the aisles of a toy store, I spotted something that set my imagination on fire. It was a box for a boardgame and its artwork depicted a muscular warrior swinging a sword in the face of a horde of goblins, his raven-black hair swinging dramatically to one side. He squatted at the foot of some steps in what looked to be an underground cavern. Two brick portals behind him hinted at a vast dungeon complex from which infinite enemies might spew forth. I was fascinated.

The game in question was HeroQuest made by Milton Bradley in conjunction with Games Workshop. Although I was too young to play it, or have any understanding of roleplaying boardgames, I was wholly familiar with the type of world its artwork encapsulated. I had grown up on a diet of Saturday morning cartoons like Masters of the Universe , Thundercats and Dungeons & Dragons . I had the He-Man toys. I pored over their box art (surprisingly grim and gloomy for a kids toy line) and I imagined my own adventures as I hacked up patches of stinging nettles and bramble bushes behind our house with my plastic sword. I loved anything with muscle-bound warriors fighting monsters and evil magic in somber, ruined landscapes. What I saw in the HeroQuest box art that day both typified and distilled everything I loved about sorcery and swordplay into one image and I never forgot it.

The artwork (done by British illustrator Les Edwards) was very much of its era. Muscles were big in the 1980s. And they were big business. Bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger exploded across cinema screens in movies like The Terminator (1984) and Predator (1986) while Sylvester Stallone starred in several sequels to Rocky (1976) as well as introducing the world to the Vietnam Vet-gone-rogue, John Rambo. The expansion of cable television ushered in a professional wrestling boom with colorful characters like Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage breaking into mainstream pop culture and becoming household names.

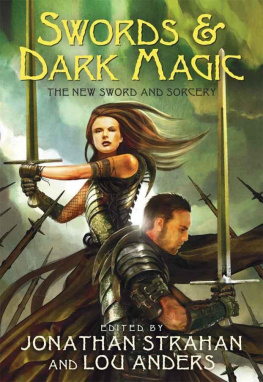

The fantasy genre was also affected by the image of the beefed-up macho man and similar images to the HeroQuest illustration could be seen in paperback spinner racks, on heavy metal album covers, comic books and movie posters. Muscles, swords, and sorcery were everywhere in the 1980s and then, as the zeitgeist evolved in the 1990s, it all vanished as if banished by a spell.

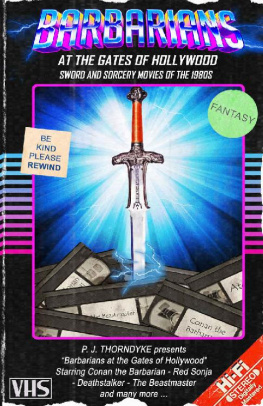

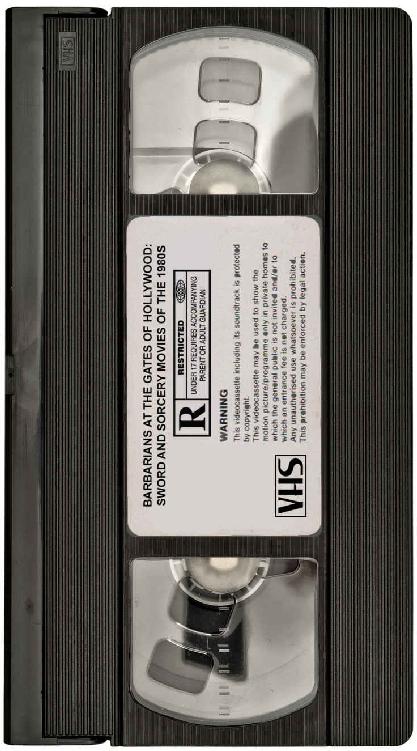

I did not know then that the raven-maned barbarian of HeroQuest, and everything else that resembled it, was part of a specific subgenre of literary fantasy that had a rich history going back decades, even centuries. Several elements came together in the 1980s that caused a boom in what is known as sword and sorcery. In particular, the silver screen (and subsequently the video rental store) became inundated with movies that fed on a long tradition. Several big budget movies opened the floodgates for a slew of imitators, providing ample material to write a comprehensive book on.

As we shall see in the next chapter, there exists a set of definitions that sets sword and sorcery apart from other sub-genres of fantasy. This explains the absence in this book of the likes of Excalibur (1981) and Ladyhawke (1985) as well as beloved childrens classics like Willow (1988), Labyrinth (1986) and The Dark Crystal (1982). This book instead focuses on the movies concerning individual warriors on lonely quests, the barbarian movies, the dirty, grimy, low-brow fantasy flicks aimed largely at adults who craved action, blood, nudity and a damn good time.

The purpose of the book is not to review every movie from the 1980s that has been labelled (justifiably or not) sword and sorcery. Many are either so surreal and offbeat that they defy criticism or are so downright bad that reviewing them on a basis of quality would be pointless. The charm they hold is largely borne of nostalgia and they are cherished by a select few who find in their datedness and cheap production values a certain guilty pleasure.

With perhaps the exception of Conan the Barbarian (1982), these movies are, at best, light entertainment and at worst, poorly-made cash-ins that wear the trappings of fantasy but in reality are little more than titillating exploitation movies only a cut above softcore porn. Most miss the point of sword and sorcery and were made without any concern for stringent genre definitions, wishing only to capitalize on current trends. They blended Star Wars style adventure with medieval romance and populated Dungeons & Dragons style settings with spaghetti western antiheroes. A better term for most of them might be barbarian movies in accordance with their oiled up, shaggy-haired protagonists who, while they may claim fraternity with Conan, the resemblance is often only skin deep (if that).

The aim of this book is to comprehensively catalogue and describe all such films from a certain point in time; a specific movement of the 1980s that was so perfectly epitomized by that HeroQuest box art I was fascinated by all those years ago.

INTRODUCTION

I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content. - Robert E. Howard , Queen of the Black Coast

The term sword and sorcery conjures images of a mighty barbarian warrior swinging an axe in the face of skeletal armies amidst the crumbling ruins of some lost civilization. Or an evil sorcerer intent on conquering the land through the use of his dark arts. Or perhaps a wicked cult of robed priests subjecting a naked princess to all kinds of terrors, daring a muscular hero to save her. Giant snakes, giant spiders, dragons, demons and wraiths; one might expect to see all of these depicted on a garish poster promoting a sword and sorcery movie, a genre that particularly flourished in a decade that gave us Conan the Barbarian (1982) and The Beastmaster (1982) as well as more low-budget offerings like the Roger Corman-produced Deathstalker series and the Italian-made entries like Conquest (1983) and the Ator saga.

But what distinguishes sword and sorcery from other sub-genres of fantasy? Why are the muscle-bound heroes and their magical quests of these films different from other fantasy films of the era like Willow (1988) or Ladyhawke (1985)? Or the likes of those titans of fantastic fiction; J.R.R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings and George R. R. Martins A Song of Ice and Fire ? All have swords, all have sorcery. All are set in far off imagined lands peopled with strange races, demonic beings, and brooding gods.

The Lord of the Rings has been labelled epic or high fantasy, and it clearly differs in content and mood to the plots of films like Conan the Barbarian (1982). This difference is not simply a matter of literature versus cinema with the latter being a simple tale designed to fill a couple of hours while the former is a hefty thousand-page epic telling of wars and thrones and shifting alliances. As we shall see in this chapter, the differences between these two sub-genres of fantasy lie in emphasis, motivation, and themes.

The term sword and sorcery was first coined by Fritz Leiber (author of the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories) in 1961 as a reply to a question posed by fellow fantasy writer Michael Moorcock (author of the successful Elric tales) as to what this genre of fiction they were writing in should be called, stating;